The sculptures of Ronit Baranga deal with complex ideas about the human condition. Human bodies, mouths, hands, fingers, expressions, attitudes and postures draw the viewer into powerful and emotive works. Her art reflects the world in which she lives, and deals with universal ideas that anyone can relate to.

Ronit Baranga interview conducted in conjunction with her editorial in Issue 020 of Beautiful Bizarre Magazine. We hope you enjoy!

Ronit Baranga

Interview with Ronit Baranga

Ronit Baranga’s work deal with the human condition articulated through expressions, attitudes and postures, even of parts of the human figure, draw the viewer into works where often these bodies are trapped. In ‘Mimose Pudica’, “craving hands emerge from the walls into the space, like a gaping body longing to touch and feel”. ‘Hands’, “emphasizes that the stretched fingers are not playing but rather supporting a delicate structure which sole existence depends on the tension of the fingers”.

In creating ‘Borders’ you have said that you “express complex emotional feelings by creating sets of incompatible images, combined as one… the mouth is an opening to the human inside, physically and metaphorically. The combination of fingers and human mouths on plates and cups, appearing as one, creates new hybrid items that “feel” their environment and respond to it.”

How much does your background growing up in Israel affect your work? Does it form part of your inspiration or underpinning ideas? Do you feel that we live in an increasingly dangerous, but numbed world, where violence, tragedy and horror (particularly where you live) are almost the norm? Do the extreme emotions and the images of tied up or struggling humanity in your sculptural pieces, come from your feeling about what is happening around you? Is this a way of reminding us of the human condition and of how to feel and express feeling? Or is it an expression of how those around you feel? Are the mouths a primordial scream?

I do deal with complex ideas about the human condition, and believe, as you state, that the world in which I live in is surely reflected, one way or another in my art, although not intentionally. However, and more importantly, my art deals with universal ideas, that anyone, anywhere can relate to. This is evident in the numerous reactions I receive from people all over the world, who care to let me know, that my art moved them. My art relates to my ability to observe, to examine and process through sculpture, issues of being a woman, issues relevant to each and every one of us, who live in a society, connected to the people around us, influenced by them and affecting them.

There is a dichotomy to your work and an element of the unexpected. Inbuilt contradictions, sometimes playful, sometimes threatening, that surprise, shock, unsettle the viewer. In particular, I am referring to the ‘Tableware’ series and ‘The Gravewatcher’s Childhood’. The ‘Tableware’ makes me smile, surprising and unsettling, as it is there is a sense of humour and whimsy. Not so much ‘The Gravewatchers’, which I am drawn to for the sheer force of expression in these infants but I am also incredibly unnerved by them as well. You described that in this “series of works there is a threatening and intimidating aspect together with sweetness and vulnerability.”

Do you employ devices such as shock, provocation, and irony, which are post-modern tactics, deliberately, to force the viewer to think and feel? Devices such as these have been used in the past to communicate to audiences by artists who felt very strongly about what was going on around them. In particular, I am reminded of the Dadaists, whose radical works were made as a protest to a world they felt had lost all reason through war. Do you think that these devices are needed by many contemporary artists to communicate to numbed audience? Is it a form of ‘screaming to be heard’?

I sculpt my art from an emotional inner necessity. While sculpting, I do not think about the audience’s reaction or how to force them to feel or think, although it is clear to me that viewers of my work will sense contradictory and opposing emotions. I hope this will fascinate them and make them think about m my art.

My way of thought is layered; I do not see the world in black or white, but rather as countless shades of layers that build a very complex reality. Even during my University days, whether in literary analysis or psychology studies, my thought was sharpened by the realization that the world is composed of many interrelated factors that influence and derive from each other. When I sculpt, I find it completely natural that there is a threatening and wild layer in the “Grave Watchers’ Childhood” sculpture while with it, at the same time, there is a sweet and heart-captivating layer; that “My Artemis” has layers of liberation, seduction and ecstatic joy alongside castration and obsessive control; and that the “Tattooed Babies” cause a sense of deep serenity alongside an uncomfortable feeling when realizing that an invasive, violent act was done to them without being aware or understanding. This is the reality, in my opinion. Life is complex. People are complex. Nothing is one-dimensional or simple.

I have read that your work is an interlocking of the living and still life. It is clear you have a deep interest in the human form. Expressions, emotions, the physicality of a figure in whole or part. Even your tableware sprouts fingers that might move a cup or teapot across a table when you are not looking and mouths that gape up at you from a plate or bowl.

Where does this interest in the human form spring from? What do you find satisfying in exploring it? Why is it important to you to integrate human forms even into plates and cups? What qualities do you feel it’s most important to capture in your figures and figurative elements? Do you do a great deal of life drawing in order to render your human forms accurately in clay? Is the human figure a metaphor for larger concepts for you? What do you want to express through the human figure?

The human body fascinates me. My work always involved people, whether drawing them, reading about them or trying to understand them. This is life itself. The human figure is such a broad topic, that it allows me to make art open enough for any viewer to see themselves in their analysis of my art.

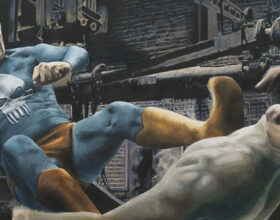

As for my preoccupation with the human body in art, for many years I drew live models at least once a week, although I did not learn didactic painting methods, I enjoyed the challenge of transferring three-dimensional objects to two-dimensional ones. I did not paint for a long time during my university studies, but ten years ago, I came back to the human form by sculpting human fingers and mouths emerging from tableware. The idea was to test and redefine the relationship between the useful tableware and the person using it. I gave them the organs we use and created tableware that can sense its environment and respond to it. They transformed from passive objects into active ones, capable of deciding whether to allow me to use them, whether to use themselves or perhaps escape from the situation. At a later stage, I began to sculpt the relationships between the sculptures, which became more and more physical. One piece of tableware leaning on another, embracing, pinching, crushing it; a violence-to-pleasure based relationship.

In recent years, I have returned to figurative art. I find a great interest, difficulty and enormous challenge in sculpting based on a model (and in some stages of the work, sculpting based on my photographs of the model). To transfer a three-dimensional image to three-dimensional art (or a two-dimensional image, a photograph, to three-dimensional art) is pure pleasure.

It’s important for me to sculpt the body as accurately as I can. I feel that when the body is sculpted without anatomical errors, the viewer is tempted to approach it, to examine it, to relate to it and to confront its content.

The infant, the mother and child are strong recurring motifs in your body of work to date. You render these with such tenderness at times, so playfully at others, and demonically in some works as well, but always so accurately, so faithfully to the forms, with so much understanding of the emotions therein, I raced to research if you had children, to see if this is where that understanding and preoccupation come from.

Did this interest, this preoccupation come from having children or was the infant, and the mother and child a symbol for you before that? What do these symbolize for you now? Is it part of an interest in the female body and femininity in more general terms? I have three children but it would be rather simplistic to say that I sculpt our relationship.

A mother-child relationship is a very complex issue that occupies all of us, from our childhood that affects the entire course of our lives to the childhood we create for our children. I deal a lot with these relationships that define a person. Although there is no doubt that my life and my worldview are sculpted into my art even without any clear intention on my part, I generally refer to this subject universally, psychologically and not personally.

In my “Tattooed Baby” sculptures, I tried to examine the idea that anyone raising a child “tattoos” them, metaphorically, with their worldview: how they think, how they behave. This worldview is “inserted” under the newborn baby skin and accompanies them all their life, unaware of it at first and without being able to “remove it” at a later stage.

“My Artemis” also refers, with some of its layers, to the very complex relationships between a mother and her children. The mother, who nourishes and is nourished, releases her children, but at the same time they are connected to her with transparent threads. This work is so complex and open – I would be happy if the viewers perceive this goddess figure, Artemis, the binding mother, seductive and castrating, metaphorically.

You work in series, the ‘Tableware’, ‘Tattooed Babies’, ‘The Grave Watchers’ Childhood’, the ‘Goddess’ (‘Artemis’, ‘Blossom, Mimosa Pudica’). Are these series ongoing and recurring themes you go back to explore regularly? If so, what draws you back to them to further explore? Do you have a point where a particular exploration seems resolved, finished, complete, and you know to move on from it? Is there one series in particular that resonates most strongly for you, or that you are most satisfied with? If so why?

I work in series, examining and testing concepts that evolve and change slowly from sculpture to sculpture. I really enjoy this precise inquiry. But despite the impression of a slow examining process, the reality is quite different. My studio is a madly intensive work environment. I work on several series at once, and my studio has dozens of works-in-progress at any given moment. In general, I make an effort to always have works-in-progress, making it easier to start the next working day. In no circumstance do I walk into the studio and think, “What will I do today?” There are always works to finish and while working on them, new beginnings come up.

I really like the “tableware” series. Over the years, it went through an extreme development process – from rigid tableware that exists between an inanimate state to a state where the tableware initially discovers the environment and responds to it, to “living” tableware, moving in space, developing physical interactions with one another and encountering sexuality and violence. Right now in the studio this series is going through another “evolutionary development stage” and something animalistic, wild comes out of the delicate China.

“The Grave Watchers’ Childhood” is also a series of evolving works. The first two sculptures were inspired by two ancient ceramic figures from the 6th century CE. Two hybrid figures of rigid, severe creatures called “Tomb Protecting Spirits”. As soon as I saw them, they made a very strong impression on me. I thought a lot about them and wondered if these stiff, threatening figures were once alive, how were they in their infancy, when spontaneity and playfulness were still possible for them, and what made them become what they had become as adults. Is this their important role, perhaps fate, is it a necessity, or perhaps it is rather their desire?

The first two figures were sculpted like the ancient figures, only as toddlers. And the other “Watchers” in the series continued this examination of baby sweetness alongside the wild and threatening side in different situations, postures and expressions. Every few months I continue to sculpt a few more “Watchers”. Mainly because they “sculpt” themselves, on their own… born alone, without intention and with lots of pleasure.

Ceramics is a delicate and fragile medium. Clay and the firing process is a reactive process and one I have found in my limited experience to be fraught with frustration at times.

Ronit, do you find this to be true, or have you mastered the technicalities of the firing process combined with the properties of the clays you use? Do you find you lose many pieces in the firing process, or indeed the entire making process? Can you explain the process of building, firing and finishing a life-size figurative clay sculpture such as ‘Artemis’?

Clay is an amazing material. It allows me to create everything I imagine, on my own, in my studio. But it is also a very challenging material. When working with clay, you can never be absolutely sure how the sculpture will come out. It takes much skill and knowledge to work with clay, understand the complex process of drying and burning it. Today, after fifteen years of acquaintance, the clay and I have reached a relationship of understanding each other and I feel calm that the sculpture I see in my imagination, I can sculpt, “release it to reality” and it will survive the entire process that the clay demands.

My work process in the studio:

At any given time, there are several works-in-progress in various stages. I work simultaneously on a number of sculptures, because the material requires different working times and because I like the diversity of starting the day working on one sculpture and ending it working on another. Usually when I work on a sculpture, I already see the next one in my mind. I do not work with sketches or drawings. I just “sculpt it out”.

When I work on a figurative sculpture, I begin to sculpt, and when the basic work stands, I place a live model beside it and correct the proportions. I repeat this process several more times. When I feel the sculpture is ready, a slow drying process begins, lasting several weeks to months, after which the sculpture enters a ceramic kiln for a slow high-temperature firing. My kiln is 80 cm high, so in case of taller sculptures, I have to sculpt them in several parts and fire each part separately (for example, “My Artemis” is built from two parts; the bottom part is slightly over the waist line. After the firing, I connected both parts to one figure standing at a height of about 160 cm). I then paint the sculpture with acrylic colors.

Ronit Baranga Social Media Accounts

Facebook | Instagram | Website

Related Articles

Musings of life & death: An Interview with Artist & Taxidermist Julia deVille