Lined with leafy streets, plenty of pretty churches and a flourishing creative culture, Adelaide is one of the lesser known creative, capital cities of Australia, and can sometimes be overlooked. But here, in this quiet, pretty place there is a plethora of incredible artists, of all genres, toiling away, working on their arts practices. Each artist, in their own way, is working towards carving a career for themselves and seeking to expand their work past the edges of this little city. James Dean is one such artist; not the silver screen James Dean, but the pop-surrealist oil painter from Adelaide.

If you adore lowbrow and pop-surrealism, James Dean is an artist to watch. James was trained as a commercial illustrator before sending his visual communication skills into the surreal. His luscious oil paintings are beautifully referential of the old masters, but, with something just slightly not right… just a little off kilter, like an oil-slicked dip into a dream or a nightmare.

Let’s take a stroll into the dreamy world of James Dean.

I have always had a fascination with the macabre, drawing dinosaurs, monsters and aliens as a kid. It is something I’ve always done. I never grew out of it.

You were trained in graphic design/visual communication with a major in illustration. How has this training informed your oil painting practice?

It has really informed composition and given me the skills to work with the large abstract shapes in a thumbnail stage and to gradually increase complexity. This ensures that I make the necessary mistakes and inevitable poor decisions in miniature where they are much easier to fix. It has also given me skills in Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator that allow me to speed up this process through digital means. I was also mentored in oils by local Adelaide artist Peter Findlay who has shared knowledge on painting construction, observation and behaviour. These two elements form the basis of my image making.

What led your path away from commercial illustration and into creative pop-surrealist painting?

I have always had a fascination with the macabre, drawing dinosaurs, monsters and aliens as a kid. It is something I’ve always done. I never grew out of it. So the jump to surrealism was mainly one of finance and opportunity. I quit my job at a publishing company and went backpacking around Europe in 2011, which was inspiring in the stories and experiences it offered, alongside some of the greatest collections of Western art on the planet. Every gallery was a step in this direction. I came back with a renewed vigour to make it as an artist.

Each of your titles seem to point to a deeper meaning. What importance do you place on the title of a piece and how important is it to you that people viewing your pieces see past the beautifully painted surface?

The titles are vital to connecting an understanding to the theme of a particular piece. I always try to incorporate a narrative quality to my work and the different stories develop as the painting progresses. I have a document full of painting names that is constantly being updated. I’d have to say that for every great title there are probably ten embarrassing ones. Sometimes the parameter of a name helps drive the direction of a piece. Other times, pieces will go nameless for a period of months. It’s an important piece of the puzzle that has to feel right

‘The Prophets of the Soapbox’ was your most recently exhibited body of work, shown at the Adelaide Fringe Festival in 2019. Can you explain your intended connotations with this title and how it related to the body of work?

This show focused on the theme of belief and how they shape our behaviour towards ourselves and others. People used to set up a wooden crate on street corners and express their views to any passers by who would listen. I guess I just imagined this noisy street corner with a multitude of people passionately shouting each other down until there is not a distinguishable word. I wanted to look at the ego as it compares with the quality of ideas.

The title does indicate a tendency to look outwards, but as I began to work on the content for the show, I began to take an introspective route too. I looked at my own beliefs relating to myself, for better or worse. I painted pictures about destructive cycles as an acknowledgement as well as step towards doing something about them.

The Prophets of the Soapbox was a stunning exhibition, each piece was so powerful. Which was your favourite piece from this body of work and why?

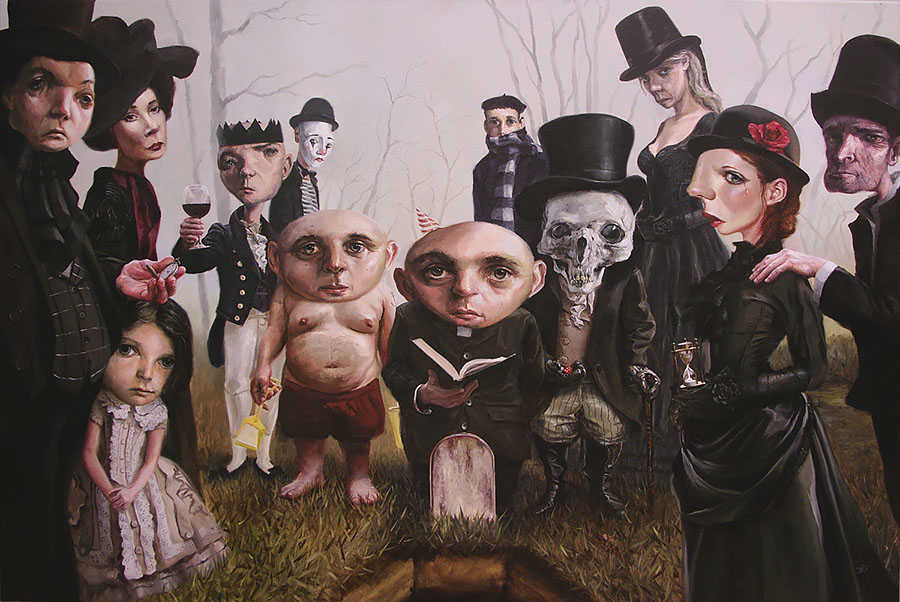

There was a piece called “A Life Examined” which is one of the more introspective pieces in the exhibition. It depicts a funeral scene where the viewer looks out at the attendees from the grave. It is an eclectic group of characters that have been sourced from my sketchbooks spanning my entire career. The earliest drawing was made in 2009. I painted it to remind myself that our time is finite, and things don’t always go according to plan. It’s a reminder to be flexible and a call to action.

You have noted, in part, that this body of work is about ‘belief and conviction’. What are your core beliefs around art and life? What are you convinced of and how does art and your creative practice fit within your own belief structure?

I hoped to instil in myself the knowledge that there are many opposing points of view and modes of thinking both personal and general. It is an attempt to move away from arrogance and a one solution fits all approach and think critically on my own position, to listen to criticism and enrich my understanding of complex problems to find better solutions and grow.

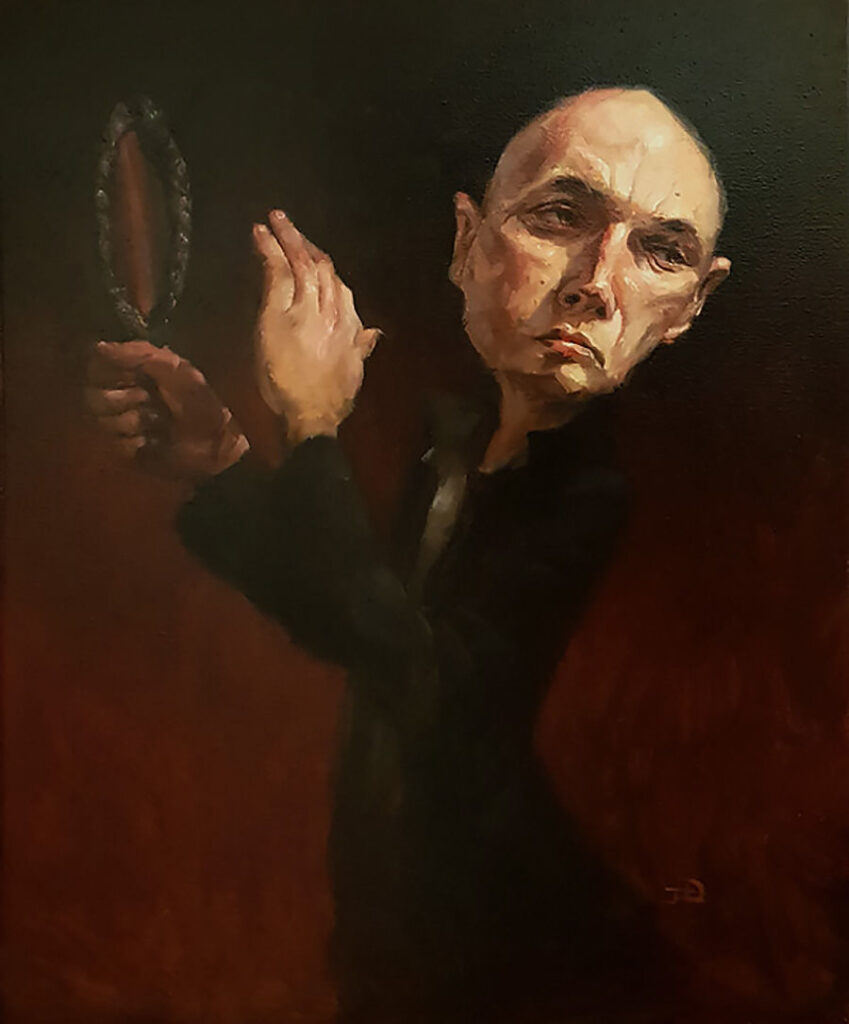

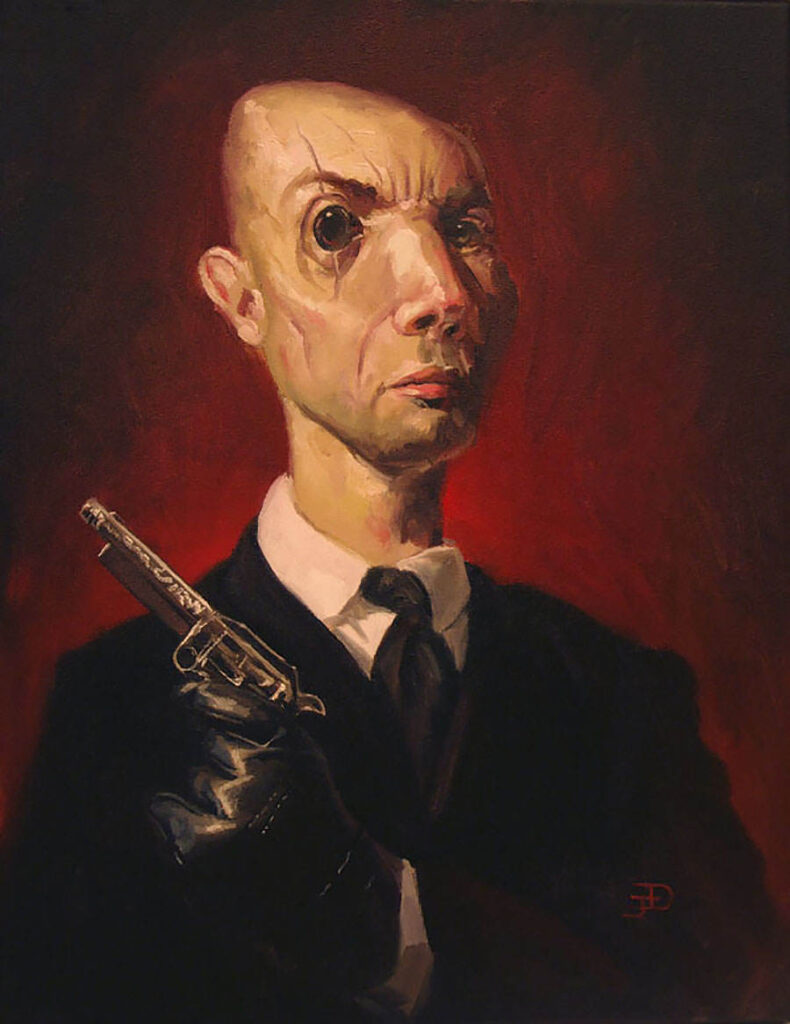

Perhaps mistakenly, but many of the characters you paint seem to be self-portraits, or perhaps portraits of your alter ego? Or just facets of you? Can you unpack for us why this is?

The main reason is that I like to collect realistic lighting reference to make my characters believable in their environments. Quite often I’ll be setting up a tripod, lights and the camera to capture a scheme that will work with the image. Unavoidably, there are a few of my own features that translate into the character.

I enjoy the blurred lines of reality and the inner world. It also offers a lot of play in interpretation.

Clowns are a consistent motif in your work; what is it about these characters that interests you so? (Clowns can be terrifying! Although, the clowns in your piece ‘The Road of the Institutionalised’ are wonderful)

I like that their identities are concealed behind costume and paint. They are residue from a show I did in 2012 named “Wisdom and Folly”. Clowns, the fools and comic relief in narratives, and I enjoy the juxtaposition of making them morose and reflective. Simply, it’s acknowledging that there might be something more going on underneath the disguise and their actions may not reflect their inner being. They seem tired of their pursuit of the laugh and I wanted to capture the momentary lapse in character.

How do you dissect, and, make sense of the ‘human experience’ through your painting?

I can only really speak from my own point of view on the human experience, but I try to think critically on my own opinions and group rhetoric to form what I hope are stories of conflict and intrigue through a visual medium.

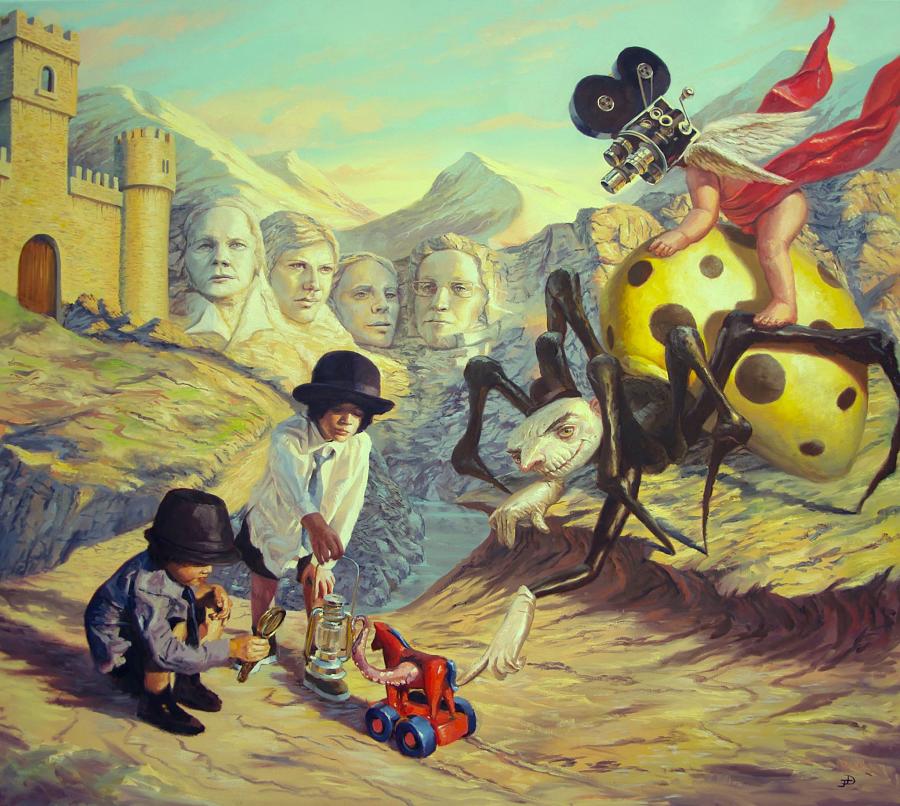

Your painting ‘The children of privilege’, a finalist in the Emma Hack Art Prize, is one of my favourites. Can you discuss what you hope people take away from this piece?

Whether it is disadvantage or privilege, it remains difficult to bridge the gap between experiences. Values, beliefs, rights, wealth and poverty can be inherited through generations of people. A culture can perpetuate itself in its lack of exposure to others in its positive and negative aspects alike. With this in mind, it is equally important to acknowledge and respect the complexity that surrounds all of our interactions as individuals and the dangers of simplistically placing people into the groups of the oppressors and the oppressed. Perhaps the waters are a little muddier than that and the answer may not be found through collective guilt, assumption or polarisation.

Surrealism for me inspires thought and challenges people to make sense of the nonsensical, which in some ways prepares them for the uncertainties, tragedies, but also good fortune in life.

Your use of light and shadow is skillfully referential of the “Old Masters” and painting of this time. What is it about this genre that you are drawn to?

Seeing any of those paintings in the flesh is something to behold. It’s the combination of purposeful brushstrokes that describe the physical world while retaining the beauty of something utterly hand made. As it relates to my work, I like to paint my characters as though they are from an earlier time, so I will often look at costumes and decor within these paintings as inspiration for my own.

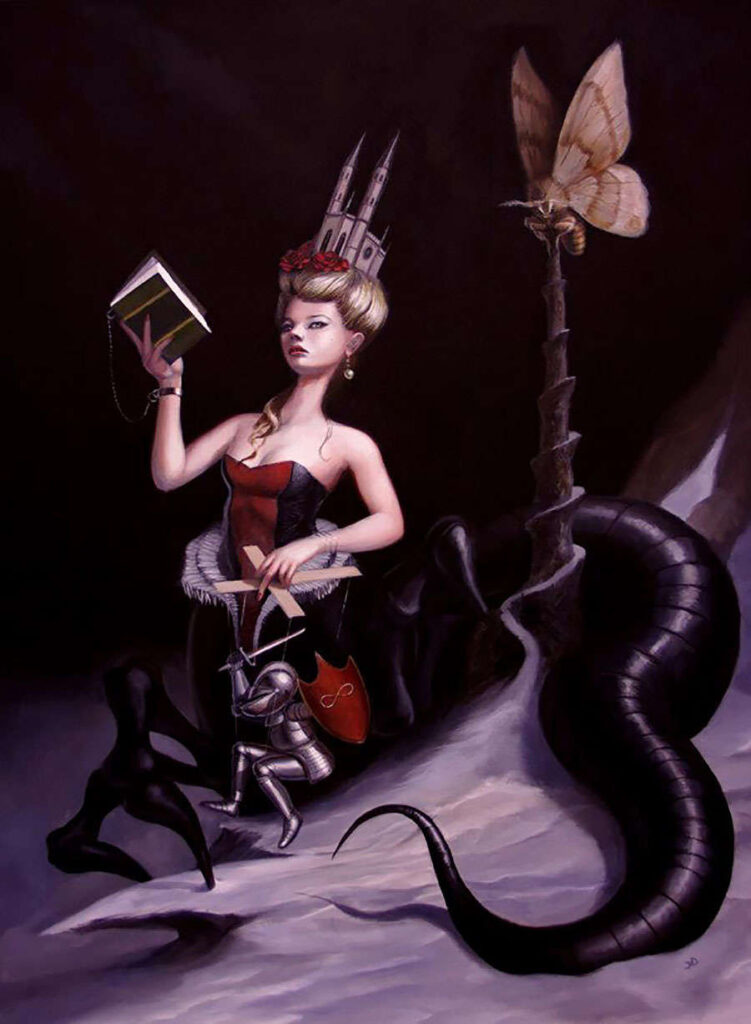

While your painting technique is borrowed from “Old Masters”, you playfully use distortion and disrupt proportion to create works that are surrealist in content, painting pieces that fit into the lowbrow or pop-surrealist genre. What do you love about surrealism?

I enjoy the blurred lines of reality and the inner world. It also offers a lot of play in interpretation. Some pieces are purposefully opaque in their content and it really forces the viewer to adopt their own meaning. Through this process I hope that pieces take on its own life. I like that surrender of control given that the process of painting it is very contrived.

Surrealism for me inspires thought and challenges people to make sense of the nonsensical, which in some ways prepares them for the uncertainties, tragedies, but also good fortune in life.

Along our creative path, as artists, while experimenting with different techniques and materials we each often tell and retell the same narrative. What do you feel is the overarching narrative you are telling with your work?

Feel, but don’t forget to think!