Exclusive Interview With Hannah Flowers, 3rd Prize Winner of the Raymar Traditional Art Award, 2022 Beautiful Bizarre Art Prize

I was always an admirer of Hannah Flower’s creations on canvas, wood, and skin, moved by her delicacy, textures, and depth, my eyes eagerly following each curvature and contour in the cabinet of curiosities she summons. Talking to Hannah allowed me to taste all the ingredients of the visual delicacies she offers to us.

And truly, I can feel Hannah’s paintings under my skin, in my guts, and on my tongue.

Helena Aryal

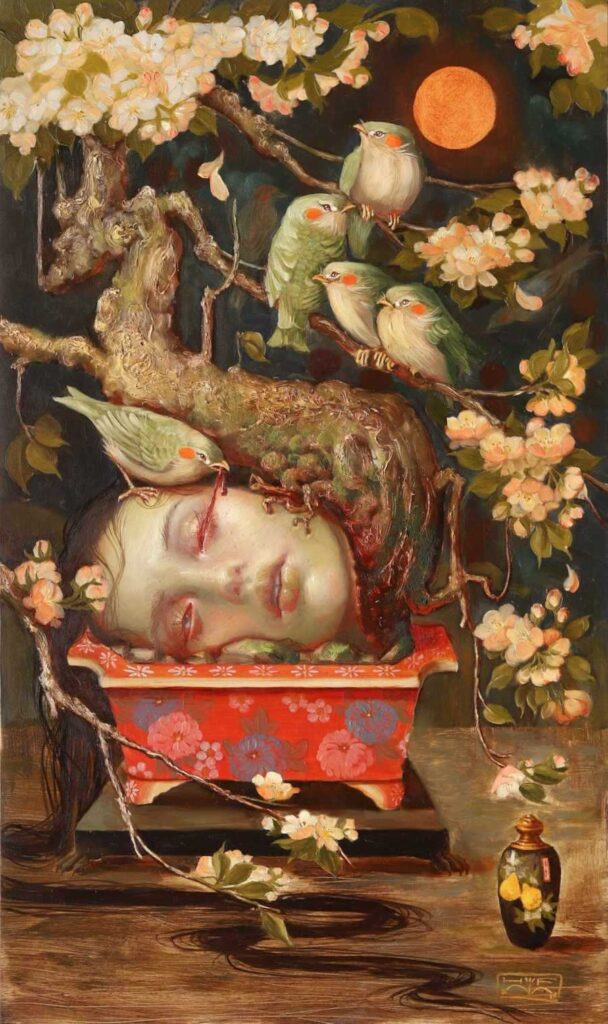

3rd Prize Winner

RAYMAR Traditional Art Award Beautiful Bizarre 2022 Art Prize

Medium & Dimensions:

Oil on wood panel, 50″ x 70″

The love for her work reaches much deeper than the first subcutaneous layer of my body: Hannah Flowers triggers all the viewers’ senses and travels from our brains to our hearts, causing a bizarre sensation in our guts with every brushstroke. Undoubtedly, Hannah’s challenging questions raised about what our society calls beauty and what is acceptable in the arts and for an artist to create, evoke feelings of enchantment, shock, appreciation and sometimes disgust – a rather exciting mixture one should experience looking at a piece of art at least once in their lifetime.

By turning one’s insides out, Hannah does not intend to shock for shock’s sake, it is much more her interest to explore the “well-known facet of the human psyche that negative experiences are remembered more vividly than pleasant ones. It seems to be a viable self-defense mechanism, the brain’s way of avoiding potentially threatening circumstances in the future”. Challenging the viewers and visually piercing the boundaries of their comfort zones results in criticism. But Hannah found her way to deal with this negativity: “In general, I react to berating humans in much the same way I react to barking dogs: Wait for my bones to stop shivering, then get on with the task at hand”.

As we stumble over more and more reasons to be enchanted, we discover an incredible depth and context to her creative practice. After realising the hard way that art degrees in Australia no longer taught any technical skills, she decided to pursue a different path to fulfil her desire to hone a real craft and use her hands to make beautiful things. Tattooing was Hannah’s first step to embracing a practice and exploring the possibilities of a medium. Naturally, Hannah reconnected to painting when she wanted to break the boundaries of skin and the requirements of working with clients and the human body, longing for a medium that allowed the artist to “play and experiment a lot more”.

Asking the artist about what inspires her to create such whimsical portraits and compositions, she explains that it is a personal relation to femininity, nature, and inanimate objects that intersect in her work. It is the feeling of connection that draws Hannah Flowers to her subjects: The identification with female characters, the passion “for buried treasures” and their different materialities next to each other in a meticulously constructed still life and the “beautiful woodland” that surrounds her become one reality in her rich compositions, full of intriguing textures and fine details.

No matter if your heart beats for portraiture, if delicate objects and symbolic still life arrangements tickle your pickle, or if you want to escape reality by entering pompous interiors and lush natural environments, Hannah Flowers has some magic to offer to everyone. But naturally, the artist looks at her work with a more critical eye.

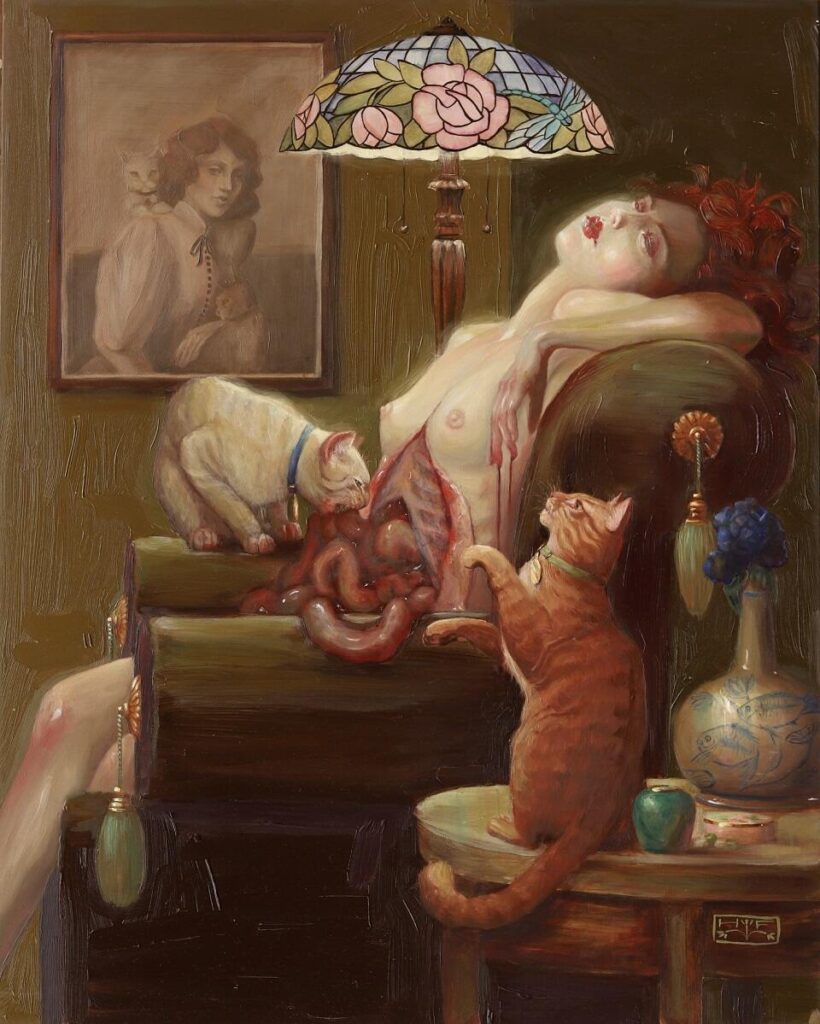

Occasionally, I feel irritated with myself for drawing the same type of girl over and over, like a one-trick pony. But I love her too much to leave her behind. I think it’s one reason I’ve been dissecting them in recent work. Cutting them open and riffling through the innards to see if there’s anything deeper.

It is precisely this twist of challenging the well-known obvious and disrupting the candid surface that makes Hannah’s creations a beautiful, bizarre sensation of gore meets beauty. A blissful experience of the paradox – here we are, joyfully diving into the depths of these innards, exploring your “glistening, wet ambiguous shapes”, appreciating the beauty of the tragic, vulgar, and voluptuous.

Exclusive Interview with Hannah Flowers

Could you outline a small chronology of your career mentioning moments, people and spaces that inspired you to follow a creative practice?

Well, as a young and naive person wishing to pursue painting, I foolishly enrolled in a painting course at a university, thinking I might learn how to paint, haha. Of course, most people now know what an absurd notion that was. Uni felt like a lot of very confused people stumbling around in the dark spouting big words to validate poorly made pictures. Apparently the policy there was that learning any skills whatsoever could damage your ‘oh so delicate’ creativity – preposterous! And it was regularly repeated by students and teachers alike ‘it’s not what you know but who you know’- contemptible! I found the experience vaguely repulsive.

At that time I had no idea of the existence of ateliers or that there might still be people alive on earth that were interested in the type of art I wanted to make. I wanted to hone a craft. I wanted the visual arts to be just ‘visual.’ Not all these pompous blustering meaningless words.

I dropped out of the course and turned my sights to tattooing. In this field, it’s only about what you know. The majority of people getting a tattoo, care about how well it’s going to be done rather than how big your name is. It was refreshing. Of course, it was a trying and difficult road to learn to tattoo, but I never had any doubts about it as I had had about the ‘art scene.’ It felt more gritty and pure. You get paid for the work done, not for your name. For 10 years, I put my head down and worked as hard as I could to become a better tattooed, and everything else fell by the wayside.

Only in recent years, as I developed my tattoo designs further, have I found myself thinking ‘if only’ as I draw. If only I had longer to do this if only I had a flat still surface to work on if only finer details would hold in the skin. I realised I really needed to paint as well to be able to fulfil the ideas I’m having.

So warily, yet hopefully, I’m dipping my toes back in the waters of fine art and finding small pockets of good people who seem interested in what I’m doing.

How does the medium dictate the content? There seem to be similarities between your tattoos and paintings, but there are also clear differences – how would you explain this?

The main things that dictate the content are time restraints, the shape of the canvas or body part, and what is going to hold in the skin. With tattoos, it’s very important to make what you do very legible so that it has room to spread and blur slightly over the years. That’s why my tattoos have more defined edges, and more contrast and are often simpler bolder designs than my paintings. One must also take into consideration that a good tattoo composition would flow nicely with the client’s musculature, which can be quite different from the flat rectangular compositions for painting.

Painting is a far more malleable medium. You can fiddle around with it, paint over or change things where necessary, so I find myself playing and experimenting a lot more. But I do try to bring what I’ve learned from each medium to the other where possible.

For example, I’ve tattooed for so long that my mind kind of works in tattoo ink colours. I often mix the colours I use in my tattoos on my paint pallet using 3 or 4 paint colours to achieve the same shades as the ink colours to which I’m accustomed. Conversely, painting has made it easier to envision things more sculpturally which has helped me make more effective tattoo designs.

What do you love about each medium, also in comparison to each other?

Painting suits my natural inclinations. To spend long slow days alone, sipping coffee, contemplating and taking my time over each decision. To put whatever takes my fancy on the canvas without worrying if anyone else likes it.

Tattooing is much faster-paced and much less comfortable (for everyone involved). But it’s very important to me. Tattooing has made me dredge the very bottoms of the barrel and pull out things that would probably have lain dormant forever. It’s often a requirement of the job to push myself far beyond what’s comfortable. When you have a client sitting in the chair, you don’t have the option to walk away if things aren’t going to plan.

You must solve the problem straight away at the moment, no matter how long you’ve been working or how exhausted you feel. It’s both more immediate with less time to think and more permanent and important than painting is. You don’t have the option to put it away in a drawer and come back to the problem after you’ve slept on it like you can with painting.

To push myself like this, to keep on concentrating beyond my natural limits has made me realise what I’m capable of when the need arises.

I have some truly wonderful clients who I have great affection for and have learnt a lot from. I’ve been invited to meet and work with masters in the field from all over the world. I know I would never have met so many new and interesting people had I been left to my own introverted devices. It’s been a richly interesting, surprising and challenging ride. Luckily for me, I wasn’t able to make a living as a painter from the start.

What fascinates you about gore and “darker” subjects?

It is a well-known facet of the human psyche that negative experiences are remembered more vividly than pleasant ones. It seems to be a self-defense mechanism, the brain’s way of avoiding potentially threatening circumstances in the future.

I suspect that could be why I find darker subjects more interesting and memorable. But really appreciation of beauty is my foremost reason to paint.

I think of it like the layers of a cake; the icing might be the best part, but it would be sickly and unappealing by itself. To me, beauty is a bit like that, entrancing and divine, but almost too saccharine without a little viciousness or amusement to offset it and allow it to flourish.

There’s always a push and pull between opposing forces in painting. I’ve not found the perfect balance yet, but I find it to be an exciting idea to work towards.

I also just love painting glistening, wet ambiguous shapes – so blood and guts are a great joy for me to paint. After I’ve sculpted the lusciously rounded innards, I lavish them with various glazes of yellowish bile and darkly cloying blood-like colours. When the paint is still wet and glistening with oil it really takes on the lineament of bodily fluids. It’s a lovely experience.

I see mostly female subjects in your paintings, is there a specific reason for this?

I think it began with wanting to feel connected to the work. I know what it is to be female so it feels more natural and personal. Putting something of myself into the stories, I was weaving. That, and no doubt being influenced by a lot of my favourite historical painters who painted women. That’s how it started. That was a long time ago. Then through my tattoo work, it’s what I became known for.

So I’ve been drawing girl faces all day every day for years for work. Now it’s become an unbreakable habit. Mostly I’m quite content and enjoy this habit. I still feel a connection to the faces. Though I would like to paint more men and have been doing so a bit in my personal work.

On occasion, I feel irritated with myself for drawing the same type of girl over and over, like a one-trick pony. But at the same time, I love her too much to leave her behind. I think it’s one of the reasons why I’ve been dissecting them in recent work. Cutting them open and riffling through the innards to see if there’s anything deeper to them. But really I think they’re just ingrained in my brain through some kind of muscle memory. Like a musician’s fingers playing an old tune without conscious thought.

I sometimes wonder if my art may have been different had I not been paid to draw lady faces over and over day in and day out for so many years. Probably not much.

How do you counter people and their negativity? How do you react to people who criticise your work?

Negativity about my paintings doesn’t tend to bother me too much, of course, it’s unpleasant, but I can shrug it off fairly quickly. Whereas cruel comments on social media about tattoos I’ve done send me into a panic! I worry my client might have seen the comment before I could delete it and feel bad about something permanently on their bodies.

But in general, I react to berating humans in much the same way I react to barking dogs: wait for my bones to stop shivering then get on with the task at hand.

It’s quite obvious you love to create portraits: How do you select subjects, and how do you compose the pieces and elements you add?

I enjoy going off on tangents too much to be very good at portraits of specific people.

I fall too much in love with the slightly wrong features I’ve made on the page that I’m loath to erase them to make them look more like the person I’m meant to be drawing. So most of my characters are made up. I’ll often use old photographs, myself or friends as starting points for the pose, but the end product is barely recognisable.

I’m searching more for a mood or character than a specific person’s features.

I live by beautiful woodland, so I’m able to step outside and sketch and photograph trees, plants and animals to use as inspiration for the surrounding elements and backgrounds. I also have some great books of natural history illustrations I sometimes use as inspiration for more exotic flora and fauna.

Of course, I can see that you are inspired by certain styles from the past: Could you elaborate a bit on how each movement inspires you? And what exactly about each style?

I love the vulgar voluptuous fleshiness of Rubens and the baroque period, the overwrought intricacies, hidden creatures and rotting elements of 17th Century Dutch flower painting, and the tragic romanticism and storytelling of the pre Raphaelites. I love the ornate beauty in the rococo movement. I’m inspired by the interesting lines, shapes and bold colours of a lot of golden age illustrators like Norman Lindsey, Maxfield Parish and Arthur Rackham.

Essentially if it’s frowned upon as pretty and vapid or only catering to the male gaze – chances are it’s my cup of tea.

I love the still-life elements of your work! Could you explain a bit about why you give so much space to objects? How do you connect these elements with your subjects?

I’ve always loved beautiful objects! I may have a bit of a hoarding problem… but it’s not really a problem if I’m using them for art… right?!

Maybe I’m only a painter as an excuse to collect things. There’s not much I love more than finding a little-known second-hand store or junkyard and greedily riffling for buried treasures. I have a cupboard filled with vases, snuff bottles, swords, cameos, moth-eaten costumes and various items of tableware.

I love different textures next to each other, and I’m always looking for excuses to add pops of colour. Certain colour combinations have me drooling like Homer over doughnuts. I’m always looking for places to sneak them in. Fruit and flowers are great for this too.

How would you like people to look at your work? Do you intend to make people think about certain topics and contexts?

No. I don’t like anyone feeling pressured to pretend to see something that they don’t because so and so said so. There’s too much of that in the art world.

If anything, I’d prefer a more physical response. When I look at a piece of art, I can tell I really love it when my eyes widen, and my heart races a bit. To dissect potential meanings ruins the experience for me.

Back to the cake analogy – if I were eyeing off a delectable slice of chocolate cake, I wouldn’t be pondering the chef’s inner machinations, dwelling on the finer points of cocoa-bean harvesting or engaging in an intellectual exploration of the possible philosophical implications of the decadence of dessert trends. Nay, I would simply salivate and think of nothing further than how delightful it may taste. As grandiose a goal as it may seem to be, I believe that the ultimate responsibility for one of my paintings to elicit in a viewer would be something along those lines. Visceral, not cognitive.