Emma Witter is a treasure hunter of a different kind. She is somewhat of a collector, even. But does she go after sea shells? No, she doesn’t. Gold, perhaps? Certainly not! What else could she be interested in picking out of her own friends’ plates? Emma Witter’s treasure are of the skeletal kind. They’re usually whitish and hard and make up a good chunk of the human anatomy. You’ve probably guessed it and if you didn’t that’s fine! Yes, we are talking about bones. Bones, somewhat reminiscent of another artist’s boney art, Eero Hintsanen.

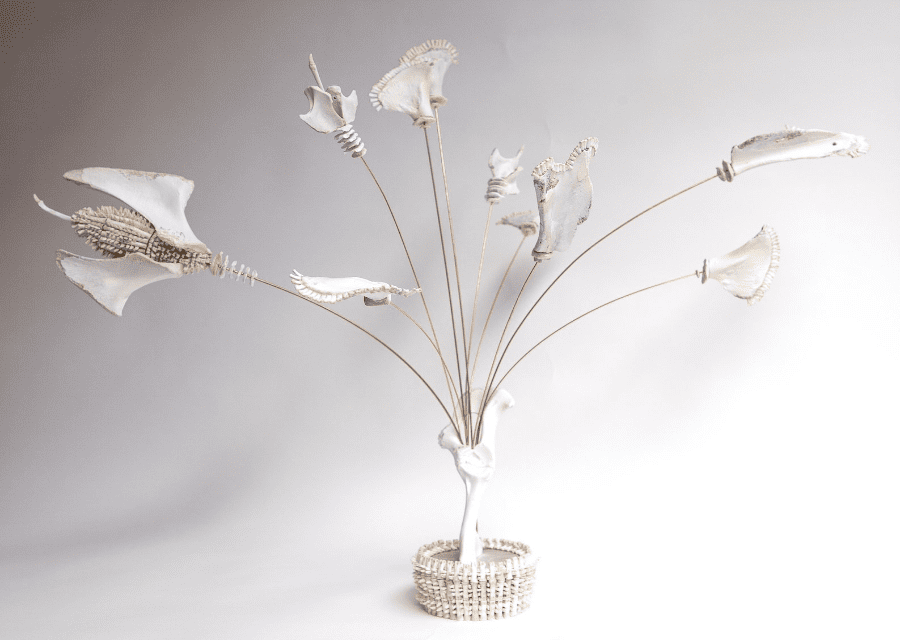

The artist’s material of choice are bones. She sculpts floral delicacies out of them. Subtle odes to nature’s infinite beauty, made to look lighter than they probably are. Indeed, she assembles pieces of bones like you would assemble a mosaic. Only this time, the mosaic is palpable. It can be held like a bouquet or serve as a vase for one.

When looking at sculptures such as You Deserved Better and Nest, we can’t help but wonder how Emma Witter renders this impression of lightness with materials as rigid as bones. It is true, that, rigidity is one of the many aspects of the material. However, the artist doesn’t see it as an insurmountable challenge.

Indeed, the artist stresses the importance of lifting a piece like Nest from a surface and attaching it into a corner wall. Most importantly, it allowed her to consider the view from below. “I focussed on tiny details, repetitions of very delicate and small pieces of bone…bird bones are good to create lightness as they are naturally porous and have a fragile, chalky texture once I bleach and dry them.” she shared.

Emma’s approach is quite minutious and she uses very small jewellery-making tools. She does so in order to chisel parts into shape, and drill holes though the bones. That way, she can thread thin brass wire through. It is a tedious task, that requires patience and attention.

The preparation of the material takes an incredible amount of time. The bones need to be collected, boiled, scrubbed, cleaned, and bleached. Then they need to be thoroughly rinsed, dried, and organized into families of shapes and sizes. “Pieces can take weeks and weeks — and I am very often straddling two or three pieces or elements at a time — but there’s a huge satisfaction in seeing a work evolve and feel intricate and complete.”

I’m very aware of this trendy sustainability ticket that everyone suddenly scrambled to attach to their products, and I’ll be completely honest that I’m not really doing that much for ecology or the environment at this point.

On a more symbolic level, Emma Witter’s bones appear to be, in some capacity, relics of the body. They are a durable material, which represents the essence or the foundation of life – which is why it seems impossible to ignore the connections between the artist’s work and potential eco-biological influence.

Consequently, when asked if her practice was rooted in the desire to anchor her work in science or environmental concerns, Emma Witter disagrees. “I’m very aware of this trendy sustainability ticket that everyone suddenly scrambled to attach to their products. I’ll be completely honest that I’m not really doing that much for ecology or the environment at this point. Hopefully, it creates an awareness of bone as a fantastic and healthy industrial material.”

Beyond ecological concerns, Emma Witter’s art is perennial. Bones resist the passage of time and leave indelible traces in human societies. Art in general isn’t always a matter of the now, it is also an attempt at leaving a mark for the future. Art is a perpetual tension towards the future and the intrinsic need for human beings to leave something behind.

The artist agrees that all works of art in any form are a small legacy and trace of ourselves, our experiences and of the time we lived in. However, for her, it is unconscious. She does not think about it as much as we think she would.

Consequently, it seems surprising, ironic even that the artist would form natural shapes such as flowers or plants with these bones. It creates a singular juxtaposition between what is meant to perish and what is meant to remain. “It feels really instinctual for some reason to form plants and flowers; growing something out of nothing. I’m playing with the uncanny.“

Indeed, Emma creates delicate fine art and elevates bones in ways that we rarely see. With a material as primitive-looking as bones, her work could have easily went sideways and ventured into arts-and-crafty territories. But the truth was, it simply didn’t.

Maybe the reason for that was the artist’s dedication to consistent craftsmanship. “Having control and flair over this material is a bit of a challenge, as bone can be quite rebellious. No two pieces are the same; there are varying levels of oils or fragility in them. They alter in moisture in relation to their environment, much like wood.”

When you take a closer look at Emma Witter’s sculptures, their mosaic-like intricacy seem to summon a sort of whispered spirituality or sanctity. Like offerings on an altar, they conjure something deeper in meaning.

It’s almost as if the pattern they traced had the power to take us back at a time, where ossuaries in Europe, served as final resting places for the deceased. Unconsciously, the artist aims to bring a sequel to the biblical adage “for dust you are, and to dust you shall return” by creating something out of what is posthumously perceived as nothing.

I’m very responsive to texture and form, and so will instead spend a long time touching and testing how different elements could sit or hug together.

It should be noted that, the lack of bright colours in Emma Witter’s universe is intentional but not absolute. She is indeed loyal to the purity of the material. However, she does not completely rejects the idea of putting colour in her work and shares her desire to experiment with colour through the application of metal.

After 3D printing her bone flowers into nylon and then plating those pieces with copper, she realised the combination of bone and copper was complimentary. The artist’s eagerness for experimentation also transpires through the idea of dyeing the bones. It is true that, charcoal is the result of a process involving the transformation of bones into powder and the mixing of this powder with oils or paints.

On a technical level, Emma Witter does not draw sketches before assembling her work. She prefers a more intuitive approach based on the communion between her senses and the material she seeks to mold. Intuition is a form of knowledge in which the known object is immediately and totally present in the mind.

The term always keeps a close or distant relationship with the act of seeing, the gaze. In a way, Emma Witter’s intuition relies not only on her eyes but on an innate sense of harmony between her mind, eyes and hands. “I never sit and sketch an idea – it doesn’t really make sense to me to do that in 2D. I’m very responsive to texture and form, and so will instead spend a long time touching and testing how different elements could sit or hug together; responding to their natural shapes, looking at combinations from different angles.”

When asked if there had been times where she projected to do something yet nothing went as planned because of maybe the difficulty of dealing with such a material, the artist cheekily replied, “Yes, definitely, they can be a bit naughty, as they are after all, still alive. Bones still have traces of proteins and oil in them; also the porousness can allow them to rehydrate a little which isn’t the effect I’m after. That’s why the prep is so important to get right.”

One thing is certain, we are looking forward to seeing what Emma Witter has planned for the future. But in the meantime, don’t miss her November exhibition, “A Moveable Feast” on The Portman Estate in Marylebone. An exhibition that aims to tell the story of time, nourishment and transitory life changes.