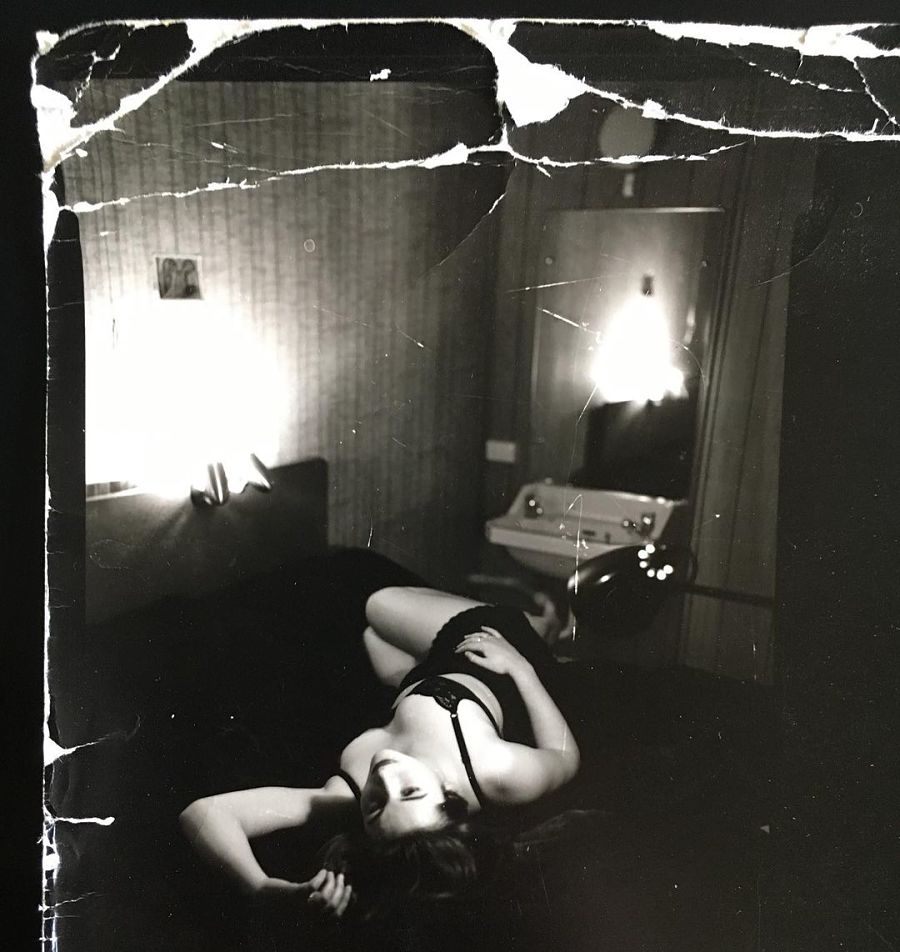

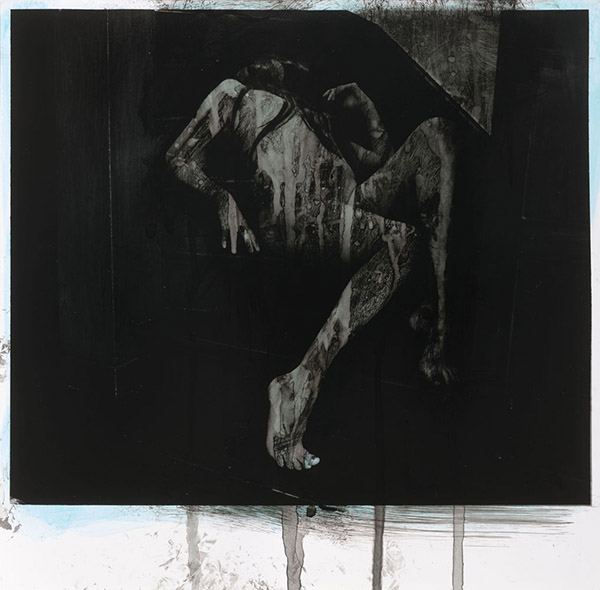

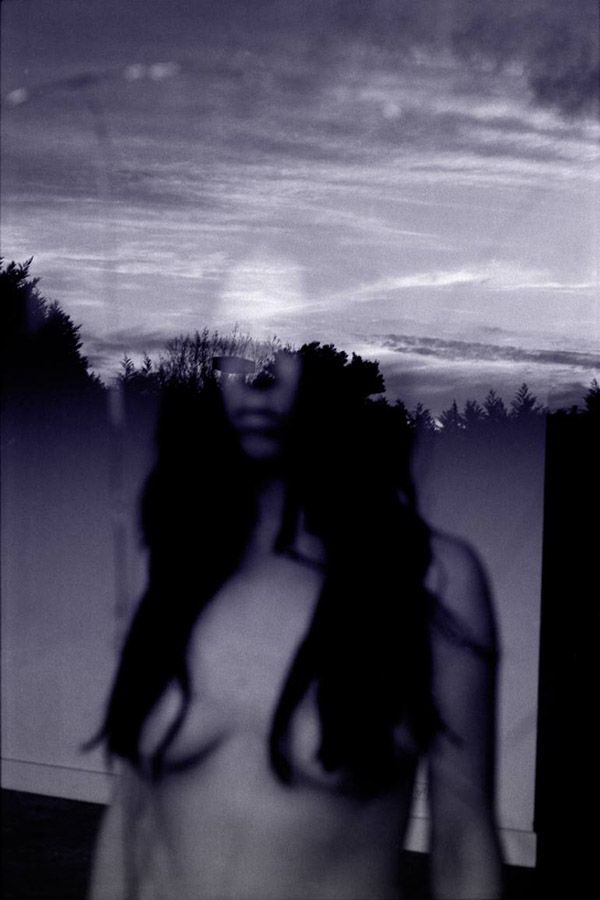

Jane Burton’s photography captures a world that knows no time; it travels fluidly through centuries. Her work fuses an enigmatic past with the present not only philosophically, but also materially. Jane uses analog film, antique photographic techniques, and more to create images of a brutal but beautiful dreamland.

Jane spent time with us to illuminate her work with words of wisdom. We hope you enjoy…

Interview conducted in conjunction with Jane Burton’s editorial in Issue 20 of Beautiful Bizarre Magazine.

My photographs are not consciously exploring mental health awareness. But I’m interested in human psychology and the connections and tensions between the physical and emotional states of mind.

I was fortunate to attend art school a year after I finished secondary school so I entered a milieu of like-minded students. I found this so liberating after feeling for as long as I could remember something of an outsider. I remember from the earliest times, feeling compelled to hold onto experiences, places and images. Art seemed to be a way to do it.

For a time, our family lived in rural Victoria and I distinctly remember the long drives through the landscape, seeing it flicker by. I apprehended the fleeting scenes and changing light like a series of pictures, one after another, but always to be lost to me. I instinctively wanted to capture these pictures, in the truest sense; the car window was a frame through which to encounter the world; something like a camera.

However, it took me a couple of years at art school to take up photography, as I was romantically drawn to painting, for its historical tradition, and its raw tactile quality. I did struggle though, with rendering my visions onto canvas. So from the first encounter with a camera, where I could capture what I saw with immediacy, and importantly, what I felt, I was seduced.

The first photographs I took were of my family and friends, ready models who posed without complaint, which was a necessity to working intuitively and experimentally. Each photo-shoot felt like a creative act, immortalising my subjects in a place and time. To an extent, this is still how I work, with people I feel bonded to, and drawn to. Sometimes I’ll approach a stranger, but usually it’s a person I’ve encountered very naturally. I feel I ask quite a lot of the models I photograph: their patience in the face of sometimes-lengthy sessions, and their willingness to bare themselves, quite literally.

I think two aspects of my early life have shaped me as an artist – the experience of growing from girl to adolescent in the country, in nature, and the growth of my imagination via esoteric art books that my father would bring home. The landscape I inhabited, the expanse, the beauty and the freedom, combined with an imagination stoked by exciting images of the Fantastic, the Symbolists, amongst others, set me alight. It was an ecstatic feeling of the awakening to one’s consciousness, sexuality, and the sublime.

Why do you feel the female body is such a powerful thing, whether through starting conversations about gender, inequality and more, and even through illustrating definitions of femininity and more? Why do you like using the female body in your work?

From the beginning, I was drawn to photographing the female body for its beauty of form and an inherited appreciation through classical representations in art history, and beyond. But a deeper answer, I think, is at the time I began photographing the nude, I was myself a young woman interested in exploring my sexuality in myriad ways: erotically, psychologically, spiritually, intellectually. I felt that the naked girls and women I photographed were a stand-in of me. I could create stories and settings for such pictures, ‘fantasies’ might be another word, and place myself by proxy within them. After all, these were my projections, my desires. Significantly, I chose girls with body types close to my own. I did then, and still do, take much pleasure from the photographic shoot, which is itself an event, something real. An acting out perhaps. Composing a picture of a dreamt-of erotic, or otherwise, scene.

So to answer your question, in my case, I photograph the female body for personal as well as aesthetic reasons, and the personal is political after all. And I’d like to add, that as a woman, I feel very good about photographing my own kind, especially in an erotic context. This has for too long been the domain of men, and their defining gaze.

Your artwork often involves sexuality and/or nudes… how do you feel about censorship on social media or in general? Have you had experiences with it yourself, and/or do you have advice on how to handle it?

I’m not on any social media so I have no experience of it. Though I’m aware of incidents when colleagues have posted my images and they have been removed because of nudity. And my work is hardly explicit.

Social media arouses anxiety in me, as I’m a private person. I like to be at a remove as an artist and prefer my work to speak for me. Serious art galleries, books, publications, films, are able to elude overbearing censorship; they are where I seek my inspiration and opportunities to exhibit my work.

At times, your photography reminds me of Victorian Memento Mori photography, as well as antique photographs of ectoplasm, and other mystical esoteric leanings. Do you have an interest in this yourself? How would you define your spiritual beliefs and do they reflect in your artwork?

I think a love of beauty, eroticism, and the mystery of death, have drawn me to Victorian Memento Mori Photography and Spirit Photography. I had personal experiences of death within my immediate family at an early age, so came to using photography as a form of memento mori. One of the first complete suites of work I made whilst still at art school comprised very formal and somber portraits of myself, my father, brothers and sisters, after my mother died suddenly. I was compelled to photograph the remaining family as a means to hold us all together. To hold on to what remained after a tragedy. I channeled my sadness into the making of a memorial.

Spirit Photography intrigues me, but more for its theatricality and mystery than a belief in its authenticity. I believe it’s well accepted that most Victorian Spirit Photography is smoke and mirrors effect but the evocations of spirits and ectoplasm that appear in such pictures are so strange they are compelling.

I’ve been told my work is about ‘ghosts’, though I understand this to be in a metaphoric sense. My pictures often attempt to capture immaterial traces of what is no more; what is yearned for; atmospheres and resonances that haunt particular places. I do think shades of my spiritual beliefs are reflected in my work, but hopefully in poetic and allegorical ways. Spiritually, like sexuality, is personal. I was brought up a practicing Catholic, which I’m grateful for; the rituals and ceremony, the morbid and bloody depictions of the corporeal body, the evocations of spirit are all a rich ground for the creative imagination.

There is an overwhelming feeling of emotional depth within your work. How do you delve deep within yourself to create work that feels so intense? Is mental health awareness a part of your story, or your concepts? How do you hope an audience will respond while viewing your work?

I am pleased if my work conveys an emotional depth. I certainly intend for my photographs to contain a psychological aura. Possibly my pictures are underpinned by this emotional quality because my work usually begins with feelings or sensations that I must find a way to illustrate. The emotional charge is a mix of conscious and unconscious intent, conveyed through the material and the elemental. Of all the elements, light is the most important to elicit a psychological pitch, an emotional resonance, and so much more.

My photographs are not consciously exploring mental health awareness. But I’m interested in human psychology and the connections and tensions between the physical and emotional states of mind. I have made pictures depicting madness; also narcotic intoxication, possession, transformation. I don’t believe so much in a static sense of self, but one that is in a constant state of ‘becoming’, for a better word. I think many of my pictures attempt to illustrate this.

What inspired your aesthetic? Do you work at all with vintage cameras or processing techniques? What is your process in creating a new body of work from concept to finish?

My aesthetic has just evolved intuitively, alongside the desire to bring into existence, in images, sensations and imaginings, fantasies. It is usual for each series of work to have a particular visual style, inspired by the emotions and associations I wish to evoke. I often shift from black and white to color photography or from large to small-scale; this keeps me on my toes. My story, concept, feelings dictate – albeit in an intuitive fashion – how the work will look. Of course, as a series of work develops, things might evolve and take flight in unexpected ways, often well beyond preconceived beginnings.

I have utilised vintage cameras and old chemical processes and these certainly have an effect upon the end result. Experimenting in this way often leads to incredible things and accidents that are godsends. I embrace this. More recently, I worked with a pinhole camera – an archaic instrument that is basically a wooden box with a small hole at one end. Light passes through the hole and makes the image. There is no lens, just a manual shutter, and strangely no viewfinder. So one must point, and shoot the scene without the facility of viewing it in a frame. I loved the magic of this… the lack of ‘seeing’, and framing more a three-dimensional experience of composing an image.

Your collaboratively made film “La-Bas” was incredibly powerful. It made me think of everything from intensely passionate relationships, both real and in fantasy, to abusive relationships and the power others can hold over us emotionally and physically. Can you speak on the concepts behind this film, and the process of creating it?

‘Là-Bas’, which means Down There, was made during an artist residency in Beijing, China in 2012. Myself and collaborator Fabrice Bigot were staying in a studio on the edge of the city, a place certainly foreign and alien to us. We had virtually no connections or support, and the weather was oppressively hot. Not to mention the density of pollution that cast everything in an ochre hue and was often manifested as an impenetrable fog. In this environment the work was born, as much from hostile surrounds, as from ourselves… our personal relationship.

On the day we filmed a central portion of the film, it was so hot we couldn’t leave the confines of the studio. We used this confinement, oppression and claustrophobia, filming ourselves in the dank, dark bathroom. The water flowing over our bodies was necessity in the heat but also symbolic of states of transformation; fluid states; states of morphing, becoming, or disintegrating. The figures are shadow silhouettes who trace each other’s movements at times, then break apart. They enact a slow dance, both erotic and sinister. Do they mate, merge, or feed? The figures belong in an alien and vampiric realm, beyond this world. They enact rituals of pleasure and pain that might be willing masochism, redemption, or a hunger for incorporation. In the end, I prefer this work to remain darkly ambiguous.

‘Là-Bas’ is also a novel written by Joris-Karl Huysman, originally published in 1891.

What would you say is your philosophy on life? What do you believe is the responsibility of the artist and/or artwork?

What a large and daunting question. As someone who is very private, I prefer my art to speak for me. It is my language. I think an artist should be true and personal. There are many ways to do this of course. I feel that every artist has a unique point of view and disposition, and this is their strength. This should be plumbed and mined; seeking always to go deeper.