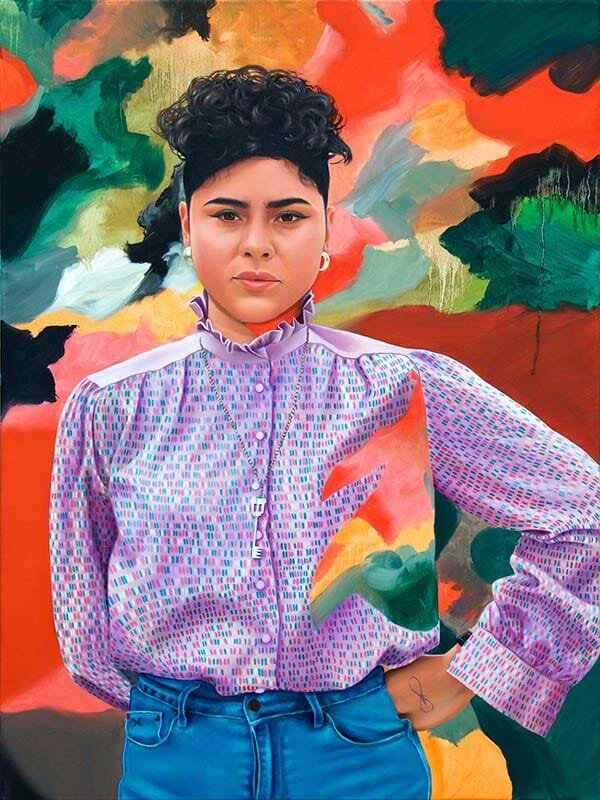

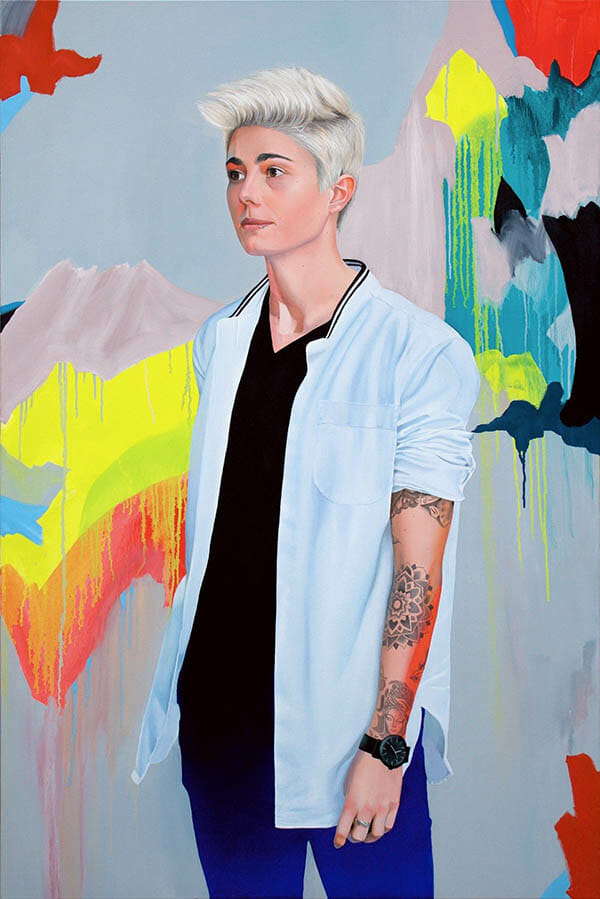

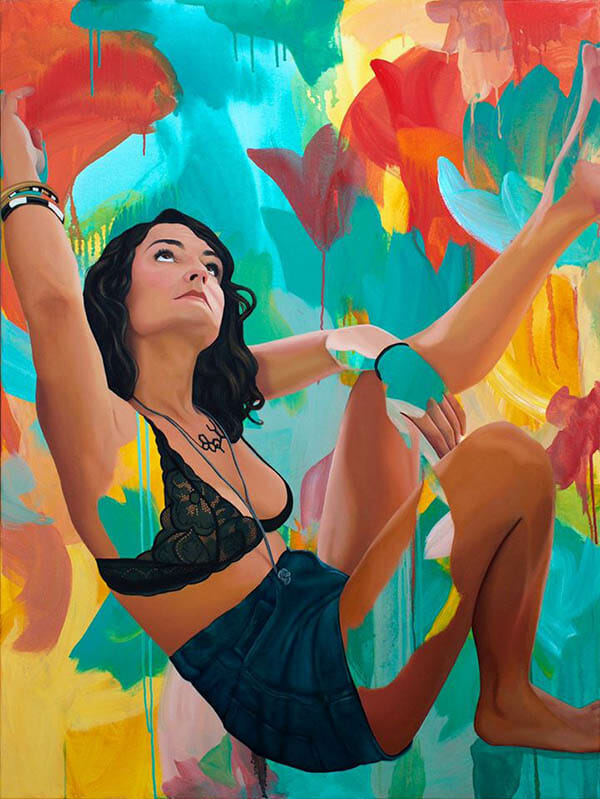

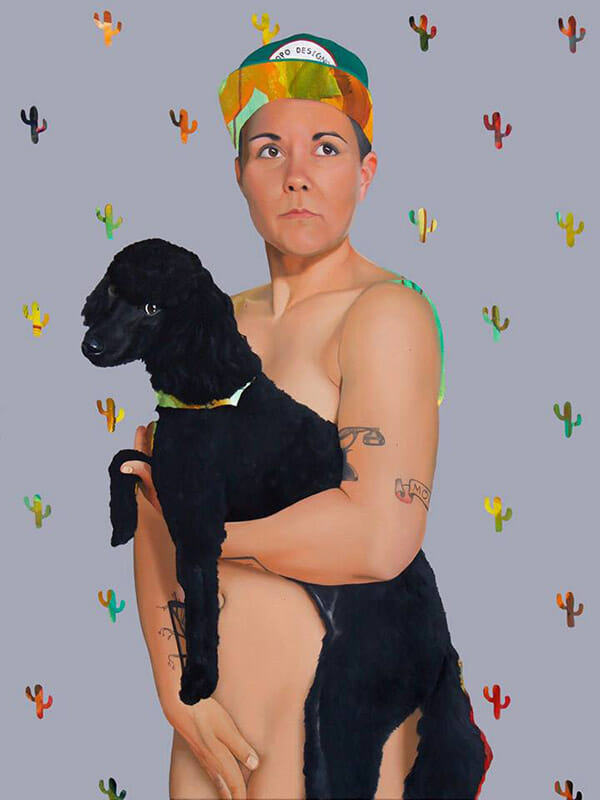

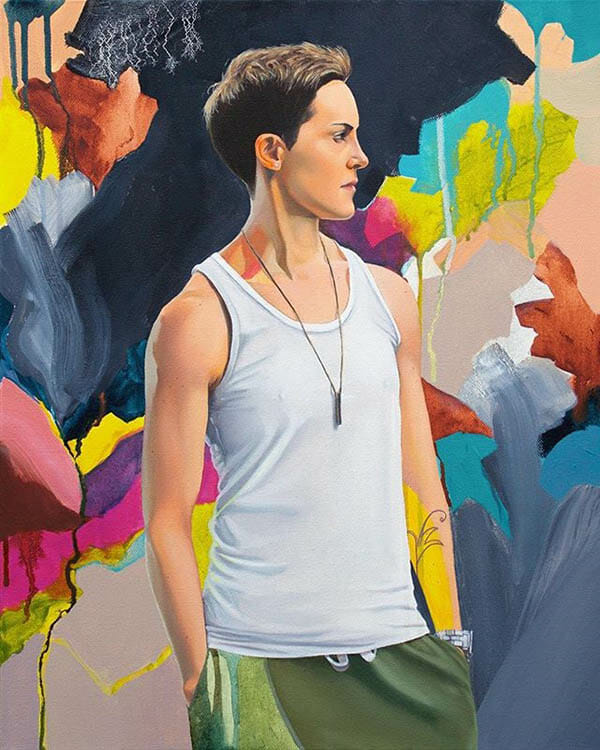

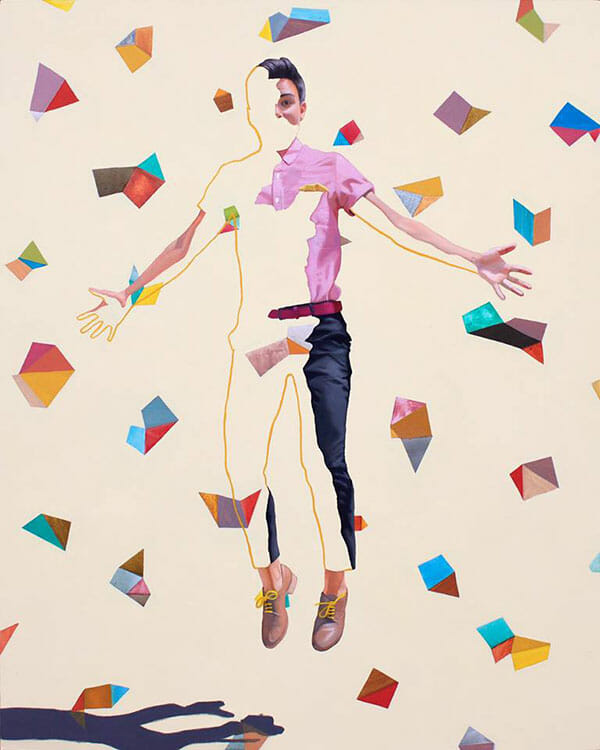

The work of American born, and now Australian based painter Kim Leutwyler is much like the artist herself, colourful, forthright, and blowing a breath of fresh air into the Australian fine art establishment. Hew works are both overtly political, concentrating as they do on members and supporters of the LGBTIQ community, and at the same time genuinely joyful works of art, beautifully crafted, easily approachable, and a pleasure to view. A two-time finalist in Australia’s best known and most prestigious art competition the Archibald Prize, held annually at the Art Gallery of NSW, Kim has made a splash on the local art scene since her arrival just a few years ago.

Our interview with Kim Leutwyler was made at an important time for the LGBTIQ community in Australia, with the public having just voted overwhelmingly to legalise same-sex marriage, a long-overdue recognition by the government of the accepting attitude for this important right by the majority of Australia’s population. The process leading up to this change in law was a fraught time for Kim and her community, with the hateful views of a vocal minority being directed at both them and their supporters. But, as the Australian press trumpeted following the vote, “LOVE WINS!”. As positive as this event was for her personally, Kim Leutwyler has wasted no time in focusing on other inequalities for her to highlight and attempt to bring to the centre of public discourse through her artistic practice.

Interview conducted in conjunction with Kim Leutwyler’s editorial in Issue 20 of Beautiful Bizarre Magazine.

The bodies of LGBTQ-identified and Queer-allied women in my paintings are evolving with their local social environment. I depict ways in which women modify their bodies, take on various permutations of androgyny, and are celebrated for it.

I don’t think we can have a full appreciation to your development as an artist, or indeed as a person, without understanding how much your gender and being part of the LGBTIQ community has influenced the life and artistic decisions you have made. As part of the generation which has started (only started, mind you) to gain mainstream acceptance and influence for feminist principles and LGBTIQ identity, how do you feel your work has caught the spirit of these times, and what resistance have you encountered to your artistic and personal expression?

Gender roles are constantly evolving, and there are a multitude of societal and cultural permutations of LGBTQI identity and feminism around the globe that make the concept of capturing the spirit of the times seem like an impossible task to me. The ‘ideal female’ has also changed over time, with varying aesthetics that metamorphose based on age, race, geography and sexual orientation.

I explore a very small percentage of the queer-identified and allied population in my work, focusing on the people who have influenced my life or my community in some way. I am constantly seeking out opportunities to meet and paint an even larger and more diverse pool of the population in the near future.

I’ve had galleries approach me to discuss representation on the proviso that I don’t advertise as an artist who paints specifically queer identified and allied women. They were concerned that the ‘Queer’ subject matter would deter collectors from purchasing my work. I advised in every instance that I’m not interested in censoring my thematic choices for the purpose of a sale. I work a full time job so that I can paint exactly what I want without having to sacrifice my artistic integrity.

There has recently been a major step forward for the LGBTIQ community in Australia with the overwhelming affirmation (over 61% in favour) by the Australian population for marriage equity via a national postal ballot – which was itself a delaying tactic by conservative groups. While this is obviously a cause for celebration, what other barriers do you feel are still in place for those identifying as LGBTIQ, as what do you believe that you can do as an artists to further their cause?

In short, the next step is anti-discrimination protections for all sexual orientations and gender identities. I can’t speak for the role that all artists can play, but I’d liked to continue making portraits of individuals who are making positive impacts on the community individually, locally and nationally. I hope that my work will stimulate a dialogue about equality and human rights in Australia and beyond. Others may choose to share stories of people who have been discriminated against on the basis of their sexuality or for being transgender, which is certainly a worthy subject for art.

You have traveled a great deal, firstly around the US when you were younger, then more recently to New Zealand and now Australia. What differences have you noticed in the local community attitudes in the places you have lived, and how much do you feel your work has been impacted by those attitudes?

As a young person I rarely paid attention to local attitudes toward my ideals, and when confronted with opposition I relished the opportunity to share my point of view, embracing a sense of rebellion. Local attitudes have never impacted me more than the present day. Having my rights put to a public postal survey was more invasive than anything I’ve ever experienced. I encountered more homophobia and additionally more support in the last couple of months than I have in the last 20 years combined. I have no doubt that this will markedly impact my work moving forward.

As for travel impacting my work… I explore fluidly expanding identities in my global travels and depict certain aspects in my artwork. The bodies of LGBTQ-identified and Queer-allied women in my paintings are evolving with their local social environment. I depict ways in which women modify their bodies, take on various permutations of androgyny, and are celebrated for it.

Yet another form of resistance and isolation that many of the artists I interview have found is that of the fine art establishment and academia against figurative or representational art and artists. Is this something you have encountered yourself, and if so how have you dealt with it?

I have been so fortunate to be supported completely in the mainstream art world and academia. In the interest of offering helpful advice many gallerists and teachers warned that no one would want to buy portraits of someone they don’t know, but I’ve found that to be quite the opposite. I’m so lucky to have a network of Collectors, Curators and reputable Artists who all encourage my exploration of representational art and portraiture.

Following on from the fine art establishment issue, have noticed a change in attitudes since being selected as a finalist for some of Australia’s most esteemed art prizes, including twice for the Archibald Prize?

Surprisingly the biggest change in attitudes since being a finalist in the Archibald Prize has been among my friends. I’ve referred to myself as an artist for years and they’ve always encouraged me, but my friends and co-workers found my self-proclaimed title of ‘artist’ a bit more reputable upon seeing my artwork on the walls of the Art Gallery of NSW and on banners and posters around the city.

Let’s dive a bit deeper into your past! As a child did you have artistic encouragement from within your family, and to follow a career as an artist?

My immediate family is very artistic in their spare time, so I blame them for my interest in art! Mom often paints, Dad dabbles in ceramic sculpture and little sis does sculpture, painting, animation, printmaking, movie props and monster makeup. After graduating high school I initially enrolled in Accounting for my University degree (I know… total nerd) and then made an impulse decision to switch to Art History. My parents were extremely supportive, especially when I layered in a degree for Studio Art focusing on Ceramics and Printmaking. They always believed in me, and I will never be able to thank them enough for that.

Who were your earliest influences and how have they changed from those you have now (these can be people, film, literature, or music as well as art, anything that gets your creative juices flowing)?

Robert Rauschenberg has been my biggest influence. I can’t explain it, but his ‘Collection’ combine painting was the first artwork that made me stop in a very crowded museum and stare for 45 minutes. I visually consumed it from every angle and digested it into my brain. The only other artist whose work has stopped me dead in my tracks that way is Ben Quilty. I also really enjoy works by Cecily Brown, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Jenny Saville, Margherita Manzelli and Romaine Brooks. There’s also a giant list of Australian artists who inspire me and we’ve built a great little community of support for one another both online and in person!

I also draw inspiration from patterns found in nature. Recently I’ve begun painting figures in landscapes that feature scenes from some of my favourite spots around Sydney. If I’m ever in a creative rut, going on a hike in the bush or a swim in the ocean is a guaranteed fix!

There is a healthy dash of abstraction that you include with your figurative work, often in a very strong palette. What are you conveying to your audience with your colour choices and the boundaries between the artistic forms in your work, and just how do you choose those boundaries?

I am constantly exploring the boundary between realism and abstraction to highlight the layers and complexity of identity and place. My love of incorporating strong colour and patterns started with studying the Pre-Raphaelites, and grew with studying Kehinde Wiley. I was fascinated with textiles and patterns employed by the Pre-Raphaelites to contemplate moral issues of justice, beauty, piety and the struggle against corruption. When I began painting women in front of their favourite patterns I was quickly introduced to the work of Kehinde Wiley, who is best known for his realistically rendered portraits of heroic figures depicted in front of decorative patterns of various cultures. Upon realizing there was another artist exploring similar juxtapositions I looked to history for further inspiration. I was drawn to the paintings of Tenebrists like Caravaggio who worked on black gesso, painting only where the light hits a person or object. I began to incorporate bright patterned backgrounds with tenebrism, blending abstraction and pattern where the subjects shadows should be. The colours and patterns reflect the taste and personality of my Sitter.

Now for the art nerds! Could you take us through your process from the selection of subject, the decision of colour palette and style, through to the tools you use to develop your narrative -and a question that seems to vex many artists, just when do you decide a work is completed?

I choose to paint the women closest to me, or those who have become a part of my community through a mutual passion for activism in the Queer community. Once someone has agreed to sit for me we meet up at my home studio or a public park and my partner takes hundreds of photos while I sketch, ask them about colour and patterns they are drawn to and capture images of lighting or details I may want to reference later. If my sitter has the time and patience I’ll have them sit for me at the studio for a couple of hours. I find this particularly important if the subject is someone I haven’t spent a great deal of time with. I’m always staring at my friends analysing their faces for lines, colours and details which makes them infinitely easier to paint! I don’t aim to create a photo-realistic rendering, but rather to convey my impression of the subject. The ‘underpainting’ usually takes 3-10 hours, after which the painting must dry. I then paint over the entire thing for another 3-20 hours until it feels finished.

To finish with, another question on sexual identity and gender, but this time focusing more on the latter. While there have been many openly gay male artists (just how openly depending on their times) who have been celebrated for their work, there have been very few female artists who were known to be lesbian, at least by the public, during their careers. What do you feel this has to say about extent of male domination in the industry, and what other changes would you like to see?

It’s astonishing how male-dominated painting has been in the western art canon. As a student it was exceptionally hard to find queer-identified women in mainstream art history books, so I turned to community articles and alternative texts. Two women immediately stood out to me during this pursuit. Romaine Brookes was a lesbian artist born in 1874 who painted her friends and lovers in all of their androgynous glory. Donna Evans presented ‘sexual deviants’ in such a way that 1990’s popular culture viewed them as unfeminine, aggressive, and unattractive as a result of their body hair, age, muscles etc. I can’t count myself among them as lesbian artists since I identify as Pansexual, but I absolutely feel connected to their work as women who depict queer-identified and Allied women.

I’d like to see more diversity in the mainstream art world. Let’s honour our trailblazing predecessors by educating others on the accomplishments of our diverse community. We need to support curators who are working to improve gender and racial diversity in exhibits and museum collections, and gallerists who promote artists previously overlooked by a male-dominated art world of the past.