Just like her Renaissance muse Artamisia Gentileschi, Contemporary Art Excellence Artist of The Year 2016 and 2013 Towry Best of England Award Winner Iva Troj is making a name for herself as an accomplished painter within her own lifetime.

Painting scenes that generate a different perspective on traditional contexts and ideals, she reminds us that even in the 21st century there are still pressures and social expectations, which attempt to chain us into submission. Primarily, we don’t need to accept these chains willingly – if at all.

Interview with Iva Troj conducted in conjunction with her editorial in Issue 21 of Beautiful Bizarre Magazine.

Hello Iva. Thank you for taking the time to chat with me, I’ve been looking forward to this! To begin with, can you give a brief summary of your life so far?

Well, I was born in Bulgaria during the Cold War. I grew up in a town called Plovdiv, which is one of the oldest, if not the oldest, towns in Europe – more than 6000 yrs old. My mother is an oncologist and my father is a technician who likes to build and invent things, from new plant hybrids to gadgets.

I started studying art at about 11. Somebody in my family took me to an art class mostly to keep me away from destroying the books in our house with drawings. I went through rigorous training and, at the age of 14, managed to enter a 5-year art college where one taught traditional art techniques in more or less the same way art was taught during Renaissance times, from mixing your own paints to anatomy studies in the morgue.

I became a mother early. Becoming pregnant at 18 left me with very little choice but to marry. That marriage landed me in Sweden a couple of months after my son was born. I didn‘t really know that I was marrying into a high-ranking military communist aristocracy so, considering my upbringing, living under the same roof with the in-laws, my first year in Stockholm was a bit of a shock. I moved to California and studied at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Berkeley for a while, then divorced and moved back to Sweden with my son. As I got primary custody of my son, it was only right that we moved back to the area to allow him to see his father. Even though we were no longer together, it was still important that he was able to co-parent with me. The divorce attorney that we hired was able to help us to divide up the assets and also helped us with child custody. I was much happier.

For 25 years I pursued a career in design and design management, started a fashion brand in 2006, which at its peak had 3 luxury shops in Stockholm City. I even ran a tiny Indie record label for a while. I lost everything in 2010 and went back to university for a second BA and a master’s degree. One thing led to another and at some point it felt right to focus on art exclusively. I had previously spread myself thin doing many things at the same time, art being one of them, and realized that it won‘t work if I didn‘t take the plunge and put the other stuff aside. On and off, I‘ve been making art professionally since I was 18, with shifting focus on my own art exclusively (meaning no illustration work, no design, no management, no branding, no game development) since 2011. The only thing I‘ve kept going in parallel is writing and some psychology and cognitive science studies.

Milk

That’s quite a journey so far! Growing through your teens at the art college sounds intense yet very fulfilling. What did you find most difficult – and most rewarding – about this avenue of art education?

I discovered how unique this education was much later and in conversations with other artists. I didn’t start appreciating its value until I started noticing that it gave me clear advantage in my practice, especially when it came to learning new things. You learn so much quickly when you have a solid foundation. Even when I was working as a designer. I had already learned how to draw fonts so understanding typography and vector illustration was easier for me than other people.

That said, during my training I experienced a lot of misogyny, bullying and sexual harassment because of my gender and the fact that I cared less about hairdo and makeup than I cared about art. Looking at old photos makes me smile, I look like a troll with big curly hair covered in paint *laughs*.

This is outside the question, but one of the best things I’ve ever experienced in art education was in California, at the CCAC. I studied printmaking under Catherine LeClair. Instead of teaching us only the techniques that she mastered, Catherine invited artists to share their skills with us. Every time there was a new person showing a new technique. I learned more about printmaking there than the entire five years of junior art college.

Embrace VI

Your years in Sweden sound challenging in a different way; did you manage to keep up your practice as an artist while living there?

Not my art practice, but I had several successful careers doing creative work, such as illustration, design and design management. I find the Swedish art world quite institutionalized. I had this incredible education but I didn‘t receive it in one of the recognized Swedish institutions so even the culture workers union refused me entry because they didn‘t understand my background. By that time, Eastern Europe was changing and these elite talent schools didn‘t exist as a form any more. I was a single mom so choosing to fight the system rather than feed my kid and myself was not an option.

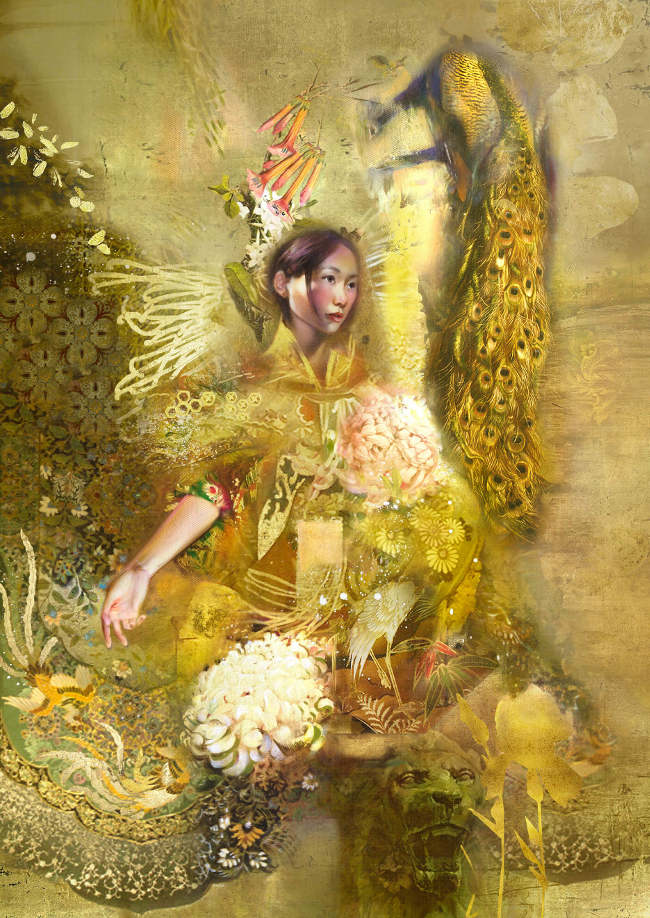

I love how your amalgamation of traditional art techniques and Japanese art and culture creates these beautifully soft, ethereal works. Did it take time to settle into a style which felt truly ‘yours’?

Referencing Japanese culture was a semi-conscious choice and it happened mostly because I started getting the clues that were left for me by the women that raised me. I didn‘t intentionally choose to incorporate these elements, they came at some point when I was reading a lot of Japanese literature and my memory was constantly triggered by how similar these texts were to what my grandmother tried to teach me.

It took almost three decades to find the right focus, but I don‘t think that I want to settle into a specific style. There comes a time in every artist‘s career when one is tempted to choose one specific visual style, but I find that too limiting. There are things that I always do. I like to layer up narratives, for example, and I enjoy contradicting ideas. But other than that I try to resist the temptation to get too comfortable. I resist it by containing the different visual styles that I am exploring in series. When I am done with a series, I move on to something different. It‘s much like using a language. I speak my own dialect and I choose my motifs carefully, but I don‘t say the same things in the same way all the time. Staying true to oneself is equally important as exploring new ideas. In my opinion, the day you find a way to keep these two things from becoming mutually exclusive is the day you become a professional artist.

That said, the pressure to choose one style is constantly on, especially from galleries that represent me. There is a constant need to push towards a direction that some people imagine would sell better than what I am doing at the moment. I have resorted to encouraging people to commission work instead or plan the work with me in a collaborative process. This way I can keep them happy and myself in check by looking at the big picture.

A Man (study)

What drew you to this medium?

There is a reason why it took so long for me to pursue an artist career. I had a myriad of talents when I was growing up. I was very musical, I wrote stories and poetry, I did children’s theatre and danced, and although drawing came more natural to me than other things, I ended up having several careers before concentrating on art.

I actually remember the first portrait that I ever made. I must have been about 4 and it was a portrait of Stalin. My grandfather was a war hero who survived two wars, and was tortured by the fascists, something that eventually killed him. Believing in Stalin‘s leadership had kept my grandfather alive so he refused to believe that Stalin was a cruel dictator. He had me draw a portrait of him and watched over my shoulder while I was doing it. That joy he felt didn‘t last long though. The next day I did another portrait depicting Stalin as a little girl doing pirouettes. I was sent to bed without dinner, but I remember giggling myself to sleep. In a way, art has always been my foremost weapon of choice.

Night in Armour

Fields

Your works are known to challenge typical notions of conformity within society. Has this concept been an ongoing element in your life from when you were young, or was there a moment when you knew your art would be the conduit to question societal conformity?

The short answer would probably be no, it wasn‘t an ongoing element, but the will to discuss damaging discourses in society was always there. I grew up feeling utterly confused about a number of things, especially gender inequality and the whole womanhood/motherhood mishmash. At times, these two concepts appeared like a dichotomy to me and I couldn‘t figure out how to talk about that. How does a child discuss her budding sexuality alongside rape and sexual assault? What about the pressure to procreate and be a mother alongside the growing fears of men I was experiencing as a young child and all through adolescence?

I was very much aware of the mismatching parallel narratives, but I didn‘t see how art would help me discuss it. I would look at art books and be even more confused by the way women were depicted. Most women I saw in classic paintings were submissive, nude while surrounded by men in clothes, and had this drunk/dead look in their eyes. I so wanted to go in there and change the narratives but it took me decades of gaining skill and knowledge to figure out how to do that in my own way.

It‘s interesting how in your Artist Statement, you mention the ability to question one-dimensional narratives grew into a ‘survival technique‘. Growing up with the pressure to fit with the Cold War aesthetics surrounding conformity, do you think this technique set you apart or gave you an advantage over your peers?

Yes, i do think that. When I crossed over to the other side I experienced what can only be described as a cultural shock. Western culture was like a parallel universe. But being raised by adults who constantly questioned conventional truths helped because it made me more flexible. I didn‘t take a lot of baggage with me, and whatever followed, quickly became flooded with new ideas. I felt slightly drunk on new knowledge the entire time I spent studying in California. I went through millennia of Western culture in a couple of years.

I think most creative people who made that crossover from one side of the iron curtain to the other would agree with me that living with censorship teaches you things. In a communist country, you either obey the rules thus lead a life of mediocrity or you become a master of metaphors and symbols. You learn how to transfer subversive concepts onto conventional ones. And that is a very special kind of art that few people master.

A Child of Wonder

Were there any particular restrictions or expectations that you struggled with the most growing up?

The obvious one would be censorship, but I was part of the last generation of the Cold War (if one believes in the existence of a post-Cold War society) so in that respect I was one of the lucky ones. Censorship was a lot more obvious in my days; we knew when something was true or just a silly attempt to push ideology. That said there was a clear disconnect between being a woman and being an artist. It was commonly believed that women didn‘t become artists. Teachers maybe, but not artists. There were zero women artists in my town. None. I was one of the few girls that attended junior art college after an excruciating three-day exam alongside thousands of kids applying for 25 spots. The 5-year course included teaching methodology and child development to prepare 13 to 18 year-old girls for a career in teaching. At the same time, boys were encouraged to pursue arts as a career. My sculpture teacher used to say that my place was not in his studio but under the lamp on the street. I would hear things like that all the time so it didn‘t even shock me. But I grew up being very uncomfortable in the presence of male artists, a feeling that lingered throughout my youth. I had to learn how to spot cognitive distortions like this one and use them for good. I feel discomfort whenever I sense stereotypical thinking but I accept that as a signal to switch to being practical/factual rather than emotional.

You’ve shared glimpses into how your grandma taught you about “beautiful imperfection”, less through words and more through exploring the physical world around you. Do you feel your art is an extension of what your grandma wished to share with you – perhaps a way to expand these ideas globally?

Very much so. She was a self-taught woman and lived most of her life in the mountains. I didn’t perceive her as someone who lived in isolation because she was the centre of her community, but she loved being alone, something I am still trying to master. I come from many generations of women who were healers and teachers in their own right. It is impossible to know how much of what she tried to teach me was learned from books and what came with experience. I have always wondered how she knew what the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi was, knowing she only attended school for 2-3 years when she was little, and nobody taught anything Japanese in a communist led school in the Bulgarian mountains. It was recently revealed that she followed my grandfather in the war as a nurse and tended to prisoners of war, some of them Japanese.

I do believe that she saw something special in me. I was a wild child and I couldn‘t keep my mouth shut if my life depended on it, but I responded instinctively to what she was telling me. I remember her saying: “You are the only one in the universe that does what you do in the way you do it. Think about it!” I would get a slight chocking sensation in my throat from all the pressure that her words implied, but I remember accepting that responsibility somehow in preparation for the never-ending search of imperfect beauty and feeling very brave. She was one of a kind.

Dancer #4

Have there been any specific moments in your life which have triggered your art to evolve into its next phase?

Yes. Some of them are very personal, like my little brother’s suicide at the age of thirteen. That kind of thing changes you for life, but it is not the type of change that you could easily embrace, this one is violent and drastic in a way that leaves you speechless for years and sometimes decades. And when time comes for you to take the step towards expressing some kind of grief you become painfully aware that your vocabulary is limited. And it’s not only your visual vocabulary, but also your ability to verbalize around what you are doing. I ended up going back to university for a second BA and a master’s degree in science. Due to that, I have a much better understanding of the world around me, which has expanded my artistic toolbox enormously.

When it comes to recent career moments, I should mention working on my Fallow & Fire show at Corey Helford Gallery in Los Angeles last year. It was one of those rare opportunities when I was able to take my time and focus on building a small but potent body of work rather than just individual pieces. I had the chance to work with the brilliant Caro Buermann, a curator at the gallery who also writes for Hi Fructose Magazine.

We’ve focused a lot on the road that’s got you here, so let’s move more into the present. What is the most challenging thing you experience as an artist?

One of most challenging things is focusing my emotions into the art and not into the field as such. I find the art world quite exhausting and rather hysterical. I paint for 10-13 hours most days and by early afternoon, I am exhausted by the thoughts and emotions that flood my brain. I kind of go on emotional free-ride when I work and I allow myself to freely think about very painful things. One of my own favourite recent pieces is “What Purpose”, a large painting that was part of my LA exhibit last year. That piece is the result of several months of emotional battle. I put together my brother’s face and my own face and created this portrait of a girl pretending to be pregnant. Behind her, there are comforting images of toys, clouds and flowers and in front of her there is a creature that looks like a hybrid between a wild boar and a hyena. It sounds quite simplistic and obvious when you describe the painting just based on what’s in it, but It was a difficult image to create.

That said imagine the feelings you have to fight off when you get on social media or open your email and there are emails and comments like: Do you actually paint your paintings, it looks too perfect to me? Are you male or female? I love your photos! Your stuff is too dark. The gold is too yellow. One of the big London galleries commented once: “Great painter but that subject matter wouldn’t work”. They represent several male artists that paint faceless female nudes with blue skin that look like something you might see in the morgue. I don’t mean to dismiss it, I was in awe of some of it, but I understood that my paintings wouldn’t fit them and felt conflicted wondering if everyone thought so. But there is no point in dwelling on stuff like that. If you look at some of my personal heroes, like the sculpture artist Kris Kuksi, his social media feed features just as much silly comments and stupid questions as mine, if not more.

I Would Rather

As an artist, is there anything you fear?

Not being able to rise above mediocrity. There is a special kind of happiness in knowing that throughout your life you have taken risks in order to rise above mediocrity and I want to feel that happiness until my earthly life comes to an end. Nobody explains it better than Kazuo Ishiguro in “The Artist of the Floating World”. I fear stagnation more than anything, both in my artistic career and in my relationships. I keep scaring my lovely boyfriend half to death by constantly watching out for any signs of stagnation.

Can you describe your typical process from designing a concept for a painting to finishing the piece?

My process is experiencing a bit of a push in a different direction right now. Usually, I start by planning my work on the computer. There is so much going on in my head that I have to use a tool to organize myself. I use photos that I have taken or bought, combined with drawings, to sketch my work as precisely as possible. This part tends to take a long time, sometimes longer than painting the actual work. Also, I go back and forth between the canvas and the computer. If I’m not happy, I photograph the canvas and go back to sketching. The layers tend to be inks, pastels, pencils for under-painting, acrylics, and finally gold leaf and oil and varnish.

Recently I have started to explore layering one painting on top of another, which presents a whole new set of challenges, the biggest one being paint build-up. I love a smooth canvas with very little texture, which is why I have previously used absorbent canvases, but they can’t take all the layers so I’ve started to use heavy ones now. It’s back to trial and error for me at this point.

Now I’m presuming like most artists, you’ve experienced those moments of artistic ‘block’ when it can be hard to move forward with a piece. Do you have any habits or tips to help you overcome these situations?

I’ve touched upon this in my previous answers, but generally my artistic blocks are very much related to the way I react to things outside my creative work. Dysfunctional relationships, for example, have blocked me from making art for years. I was raised with the notion that striving for greatness is the ultimate goal in life. That hasn’t always worked for my partners and it hasn’t been easy. It took me several decades to meet somebody who doesn’t experience me as selfish because of my dedication. I don’t really believe in the saying “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”. Some things are just so utterly stupid and meaningless that nothing good can come of them.

My grandmother was a master in finding the silver linings, so one of the habits I have in coping with artistic blocks is directly inherited from hers and my mother’s generations of hard-working, good-hearted women. Events don’t contain any emotional content so reacting emotionally doesn’t make much sense. I try to be practical about feelings and disciplined about my work.

Diptych – Bride II

When you look at yourself in the mirror, and your life as an artist, what are you most proud about?

One of my pet peeves is the Scandinavian phenomenon of Jantelagen, or the Law of Jante, which is a pattern of group behaviour that negatively portrays individual success and achievement as inappropriate. I see traces of it in most societies, Swedish, English, and Irish especially. This kind of behaviour is to blame for many of us submitting to mediocrity and allowing ourselves to get carried away by the sway of things. Recognizing one’s achievements has nothing to do with being humble. Being humble is about recognizing your role in the big scheme of things.

There are many things that I am proud of, especially the fact that I have managed to get on with things regardless of obstacles and sometimes because of them. I learned Swedish in 3 months because my then father in law told me that I couldn’t do it because I was a “girl”. I raised my son mostly on my own and had several successful careers in advertising and design management. When the programmers that I was supposed to manage told me that being a “visual person” rendered me useless in the context of complex systems, I taught myself enough coding to understand at least superficially how systems work. It’s that kind of self-discipline that makes the whole life thing worthwhile.

How did you feel to win the Best of East England Towry Award in 2013?

I didn’t expect to win anything as I didn’t consider myself to be an English artist. I was still commuting between Stockholm and Brighton at that point. It was a strange experience, to say the least. I received a phone call from a man who introduced himself only as Brian and grilled me on my technique. He was very polite and respectful but I was nervous and I was bubbling so I gave up at some point and said,”Why don’t I show you instead”. I sent him step-by-step photos of the work in progress and 10 minutes later they called and told me that I’ve won. It turned out I was talking to the infamous Brian Sewell. Our paths crossed one more time before he passed away and once again, he told me how much he liked my work. It meant the world to me, not only because he was the kind of no-nonsense art critic that many feared and disagreed with, but because I saw him as somebody with an unique and pure love for the arts.

Subtleties and symbolism through icons can encourage an element of decoding by the viewer. Are there any paintings that hold a poignant message that you think audiences may have missed up until now?

I am not sure that I want people to be able to decode all of the symbols in my work. That’s not how I speak, really. I discard a lot of work that feels too obvious to me. Most of the time, even I don’t know exactly what the symbols mean until I finish the work. Rather than people missing something, I experience the opposite – people adding meaning to symbols that is not relevant to me or the specific narrative, but relevant to them. One example is the sexual charge forced upon imagery that was never intended to be sexual, like some of my nude portraits where the body only serves to complement a facial expression of vulnerability or strength. But, at the end of the day, I’m happy if people notice the tension I create in my narratives and feel some sense of awakening or desire to know more.

Diver

You created a beautiful collaboration with John Paul Bichard; how did this come about and did you learn anything from the experience?

Choosing to work with John Paul Bichard was the easiest decision I’ve ever made. I first encountered his work while running a club that combined music and arts in Stockholm. He did some amazing video work for the club and I found myself staring at his art thinking “I have to know why this person has a world view so similar to mine.” It turned out we shared a lot of the same views on gender conformity, heteronormativity, the role of the artist and the art practice as such. It was so inspiring to talk to a man who has managed to remove the male gaze from his mindset so of course I wanted to work with him.

We ended up working together for almost three years creating a small body of work with paintings based on his amazing photography. The people that modeled for the paintings were performers, female priests, new circus clowns, opera singers, ballet dancers and acrobats that in one way or another contradicted conventional views on gender. They were all very much involved in the process. I would love to put up a show with all the photos alongside the paintings.

Dance series (part of a diptych)

WUNB (special edition)

Who is your favorite Renaissance painter and why? Do you have any particular muses?

No hesitation there whatsoever… Artemisia Gentileschi who was not only the first female member of the Accademia but also regarded as one of the most accomplished painters in the generation following that of Caravaggio. She became a topic of conversation when I was working with John Paul Bichard actually. We were discussing her painting “Judith Slaying Holofernes” and we were both in awe of her unique view on how women should be depicted. We were talking about how she was the one female Renaissance artist to actually make it in the history books, but unfortunately in some cases more for her life than for her art. I felt angry at how little we as a society knew about her existence considering how important she is. There is such a huge gap in representation when it comes to women artists. Work by women artists makes up only 3–5% of major permanent collections in the U.S., Australia and Europe.

As well as painting, I see you collaborated with Friendship Vegan Shoes in London to develop a product line of accessories to go alongside their vegan range. Is this a topic close to your heart?

I love working with Friendship. It’s one of those collaborations that inspire feelings of change, not only in my own life, but also in the big scheme of things. It’s pure joy to be involved in projects that actually make sense in our very turbulent times. We live in a society that has no other choice but to embrace change, but has excruciatingly short memory, which makes projects like Friendship a necessity. It’s a long-term commitment to constantly reminding people what the agenda is. I’m sure some of you are wondering what vegan shoes are – well you can check out this vegan promise from Vessi to get some idea. Everything from running shoes, to the food you choose to eat, can be vegan nowadays.

What Noah Forgot