How to Plant a SEED

In art school, in the early nineties, people still threw around the provocation, “How come there are so few great women artists?” That line of inquiry has been losing its teeth ever since then as each new wave of talent emerges. As someone who witnessed that era it is a fine thing to bask in the brilliance of a show like SEED. In this exhibition you can enjoy our historical moment as that old question and its sexist underpinnings are being consigned to the dustbins of history.

The 29 artists gathered at Kasmin Gallery for SEED are an onslaught of female power. Abstract works make up part of the show but many of the canvases on display explore new frontiers of figurative painting. The vision is driven by high profile art stars like Yoko Ono, Lisa Yuskavage, Cecily Brown, and Wangechi Mutu, rising luminaries such as Robin Frances Williams and Claire Tabouret, and some artists such as HeiJin Yoo who are having their first New York Show. This group of artists practice wildly divergent styles yet they are bound together through subtle means by a new curatorial voice. On the giant window at Kasmin Gallery the lettering spells out “SEED CURATED BY YVONNE FORCE”. This kind of recognition of the curator is trending. It calls attention to an often hidden yet important way careers are built, art is sold, and perhaps even art history is made.

I talked with Force about the creation of SEED. Her story provides a glimpse of how an ambitious New York show comes together.

Force has been part of the scene for years. On her first day at Rhode Island School of Design in the late ’80’s she met fellow student Doreen Remen. Together they have carved out a unique niche in the art world, founding two very successful organizations that fund public art: the Art Production Fund and Culture Corps. Producing projects such as “After Hours: Murals on the Bowery” featuring the work of artists like Kerry James Marshall and Dana Schutz, among many others, and “Seated Ballerina” a giant inflatable by Jeff Koons at Rockafeller Center, Force has gotten to know an extensive list of art world celebrities including people like Shepard Fairey, John Currin, Yayoi Kusama, and Marilyn Minter.

Yet, even with all her prior experience, when Kasmin Gallery’s Danny Moynihan suggested she should put together Kasmin Gallery’s summer show it still took her way outside her comfort zone. While Force had made a couple exhibitions in the nineties she was not an experienced curator by any means. Kasmin Gallery is a big gallery, with three exhibition spaces in Chelsea. Readers of Beautiful Bizarre might recognize it as the blue chip gallery that boldly picked up Mark Ryden way before pop surreal was on the radar of that part of the culture. Kasmin has catapulted his work into new realms. Just the real estate the gallery sits on must be worth a pretty penny, necessitating a certain level of success to their shows. On the other hand summer is the gallery off-season, a time for taking risks.

Force jumped in with the same vivid intensity she had brought to her public art production companies, devoting the next four months to the exhibition. The first artist she approached gives a glimpse where her concept was headed. “I asked Jessica Craig-Martin before I even knew what the show was going to be about.” The society photographer’s fine art work has a twist on feminine power that Force more consciously developed later. The photo selected for SEED feels almost ritualistic. It shows three mature and jewel encrusted female hands clasping at a high society gala. Force describes it as feeling like “A kind of Pact”.

Jessica Craig-Martin, Equality of Outcome, 2017, C-print on dibond, 36 x 28 1/4 inches, Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery.

SEED | Curated by Yvonne Force

Exhibition Dates:

June 21 – August 17, 2018

Paul Kasmin Gallery

293 Tenth Ave, NY, NY

Participating Artists:

Theodora Allen, Morgan Blair, Sascha Braunig, Cecily Brown, Ginny Casey, Jessica Craig-Martin, Lacey Dorn, Rachel Feinstein, Vanessa German, Loie Hollowell, Shara Hughes, Baseera Khan, Sanam Khatibi, Kate Klingbeil, Hein Koh, Emily Marie Miller, Wangechi Mutu, Sophia Narrett, Katherina Olschbaur, Yoko Ono, Ebony G. Patterson, Sarah Peters, Ruby Sky Stiler, Claire Tabouret, Ambera Wellmann, Summer Wheat, Robin F. Williams, HieJin Yoo, Lisa Yuskavage, and Sarah Zapata.

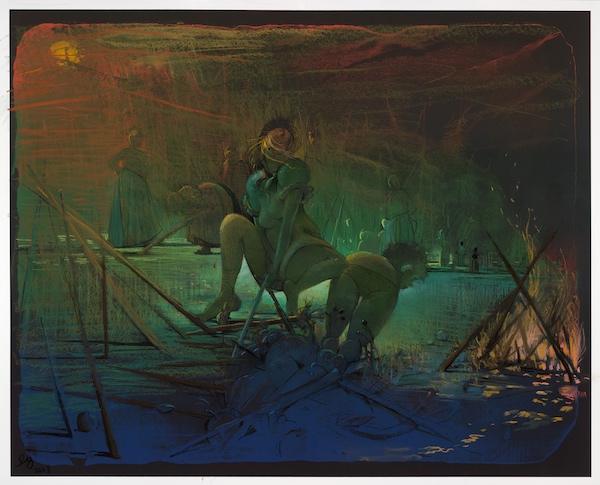

As the idea for the exhibition solidified it became about how “Women always have to defend our innately powerful positions.” The show would “Celebrate different modes and types of power that women have.” This in mind, she approached one of her close friends, Lisa Yuskavage an powerful painter who has shown at places such as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. “She was very helpful in having an intensely deep conversation about ideas.” The image Yuskavage provided for SEED may serve as a kind of touchstone to Force’s way of dealing with figuration in the show. It has a primal feel, burning sexuality, and a subjective approach to characterizations of the female form.

Lisa Yuskavage, A No Man’s Land 2, 2013, monoprint with hand additions in pastels 48 x 60 inches, Courtesy of the artist and Universal Limited Art Editions. ©Lisa Yuskavage / Universal Limited Art Editions.

Force proceeded to bring together some of her friends as aesthetic anchors: Yoko Ono, Cecily Brown, Wangechi Mutu, and Rachel Feinstein. Then she developed a massive list of “about one hundred seventy artists whose work I love.” It included artists whom she knew of but never worked with, some gentle suggestions from Kasmin gallery, and people she discovered via extensive on line searches.

Gathering this giant group was essential, but then it had to be winnowed. Force refined it to near 30 but was compelled to seek a number with personal significance. Astrology is important to Force. When reading the stars a full epoch of a person’s life takes place with each complete orbit of Saturn, a journey of 29 years. This sense of a living total aligned with Force’s vision of SEED. Thus 29 artists in the show.

Art and Alchemy

How exactly did she go from 170 artists to 29? This process of honing the vision calls attention to Force’s specific vision for the exhibition. The power of SEED is that it focuses almost exclusively on one process of achieving reference to the human form despite the different artist’s wild variation in medium and style

To explain this point it is best to look at what kind of depictions of the human body the show avoids. I can think of Five popular forms: 1) Figures based on photos, 2) Works based on direct observation, 3) Doll-like depictions, 4) Cartoon-like simplifications, and 5) retro stye imagery lifted from illustration and art history.

When asked why she hadn’t included work derived from photographic sources she replied that she hadn’t thought of things in that way. Instead she was drawn to an approach that could be seen as a sixth category. “For me it was about paint and the alchemy of the material itself creating a figure.” she explained. In this process the medium is the originator of form when married with the images in the artist’s mind. The work is less derived from existing objects or rules and more directed by mental pictures. This manner or conceiving of the subject is obvious in many of the pieces in the show. In others is more subtle but arguably still key to meaning. Force’s navigation of this concept through many mediums and degrees of abstraction creates an intriguing unstated unifying theme.

The art also exists within other inobvious limits. With the focus on power and archetypal modes of determining one’s own fate in society, it was turned away from aspects of identity that are more a compulsion of biology. None of the work is about child birth, nursing, or menstruation. Sex, however, is still on the table and all over the show as an expression of power and freedom. SEED revels in the still growing and still new field of visual poetry emergent from empowered female sexuality. As evidence of the gains in the sexual politics of our art historical moment the male gaze is not much of a topic here. Force asserted, “I didn’t want Venus.”

Which brings us to the final definitive quality of the “ritualistic and primal” for Force: no overt politics. “I didn’t want any text or political statements.” She further explained that this was not because of any hesitation towards activism. “I am a feminist. I do march. I am very involved in the sociopolitical work of maintaining our place in society…but I do believe we have this.” It is my understanding that the ’this’ she refers to is the subject of her vision with SEED: contemporary women artist’s ability to celebrate and forcefully express archetypal manifestations of female power. This is a thing in of itself.

Looking back Force says, “I could get any kind of criticism about this show and it would not bother me one bit because I feel so good.” It seems inevitable that her hope for the show will be fulfilled, that the show will truly serve as a SEED. A beginning. A thing which shall take root and grow.

Follow Yvonne Force at:

See her new curatorial efforts at CultureLab

A Selection of the Works of SEED

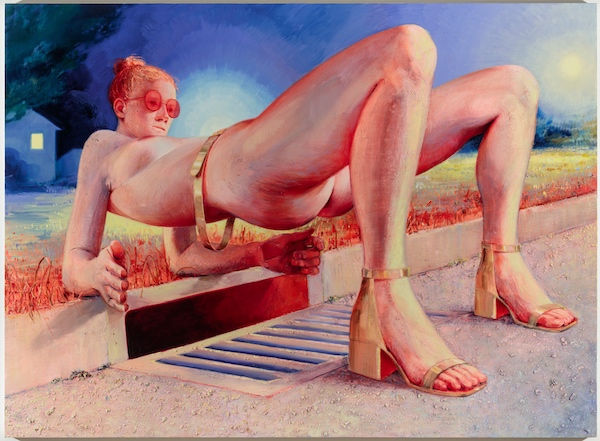

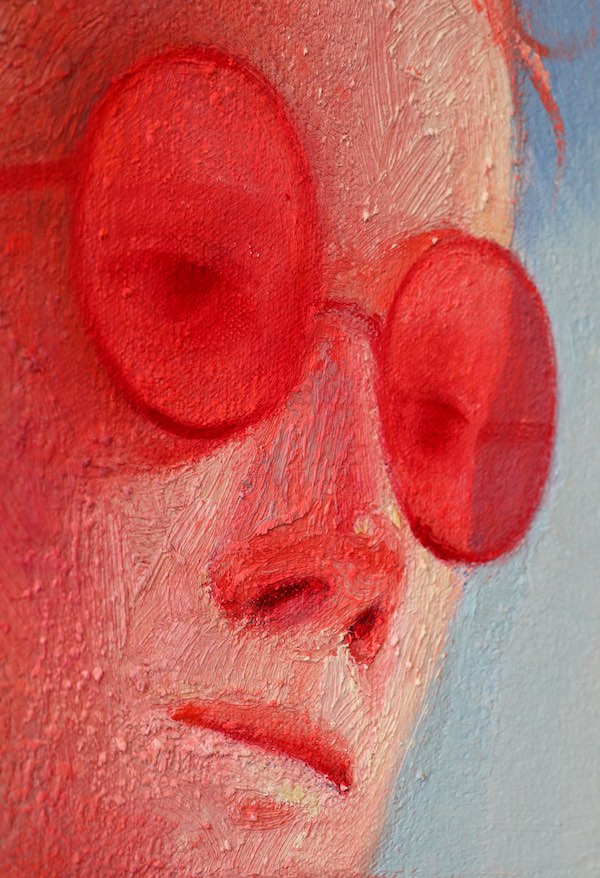

William’s fabulously surfaced, largely illusionistic figures appear to spring from her mind. She can distort and compose the human form at will to serve and create the meaning of a painting. In SEED her large scale canvas commands the entry way, its figure having a near architectural presence.

Robin F. Williams, In the Gutter, 2015, oil on canvas, 63 x 84 inches,photo courtesy of the artist and P.P.O.W, New York.

Robin F. Williams, In the Gutter, 2015, Detail, photos by Matt Mitchell

German’s work has the emotional gravity of its own planet. Although she is described as an artist of assemblage I would argue that the meaning of her sculpture here is locked in the face. German purposefully manipulates cultural references of pride and pain, modeling a visage that is part ancestral African mask and part appropriation of racist imagery. The mouth area distends caricature-like from the elegantly constructed masses of the rest of the head. It culminates in lips made of shell. Too white, too clamped, they are also a natural armor, with their hardness mirrored by the cut stone highlights blazing in the eyes.

Vanessa German, sometimes i want to kill you #2, 2016, mixed-media assemblage, 76 x 24 x 16 inches, Photo courtesy of the artist and Pavel Zoubok Gallery, NY

Vanessa German, sometimes i want to kill you #2, 2016, Detail, Photo by Matt Mitchell

Olchbaur has the ability to create a masterful abstraction employing not only anatomy but animated gesture. These legs are positioned and constructed for stride. How do they happen to have exactly the right line and position, the correct color and proportion to both complete the abstract composition and to flow forth from that floral shape?

Katherina Olschbaur, Sailor In A Sea Of Possibilities, 2018, 2018 oil and oil stick on canvas, 78 3/4 x 78 3/4 inches, Photo Courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery, Los Angeles.

Echoing the spacial distortions of a reflective porcelain surface Wellman riddles her figures into a cubist space of boundary-less eros.

Ambera Wellmann, In Teeth, 2018, oil and soft pastel on linen, 25 3/4 x 27 inches, Photo courtesy of the artist.Ambera Wellmann, In Teeth, 2018, oil and soft pastel on linen, 25 3/4 x 27 inches, Photo courtesy of the artist.

Ambera Wellmann, In Teeth, 2018, detail, Photo by Matt Mitchell.

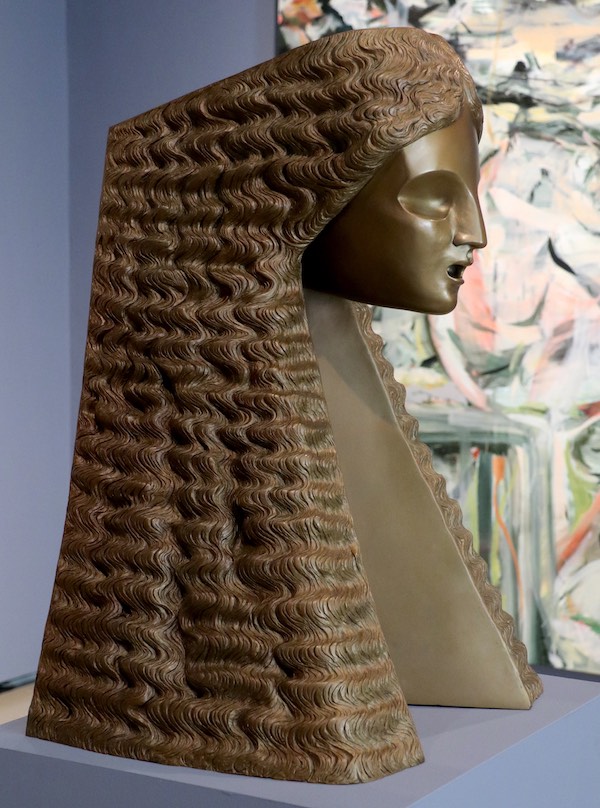

A melding an art deco machine aesthetic with the geometry of Assyrian architectural sculpture and something of the romance of the pre-raphealites, the assertive structurality of the coiffure is all Peters’. Rather than a precision polished form, close inspection reveals the small textures of hand shaping in the hair and face. The work becomes a tactile assertion of mythic force.

Sarah Peters, Figurehead, 2018, bronze, 30 x 21 x 16 inches, Photos by Matt Mitchell.

This figure seems to ecstatically violate all the expectations of its own construction. The supermodel-like base form and gesture is hacked into and globbed onto with some substance looking like play dough. Yet tube-like boneless fingers and a dessicated forearm belie this idea of the destruction of an idealized underlying shape. Then, out of left field come the flat steel cutout wings printed with pixelated color. A euphoric smashing of conventions.

Rachel Feinstein, Ballerina, 2018, hand-applied color resin over foam with wooden base and painted aluminum with printed vinyl base, 85 1/2 x 31 x 27 inches, Unique. Photo courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.

Rachel Feinstein, Ballerina, detail, Photo by Matt Mitchell.

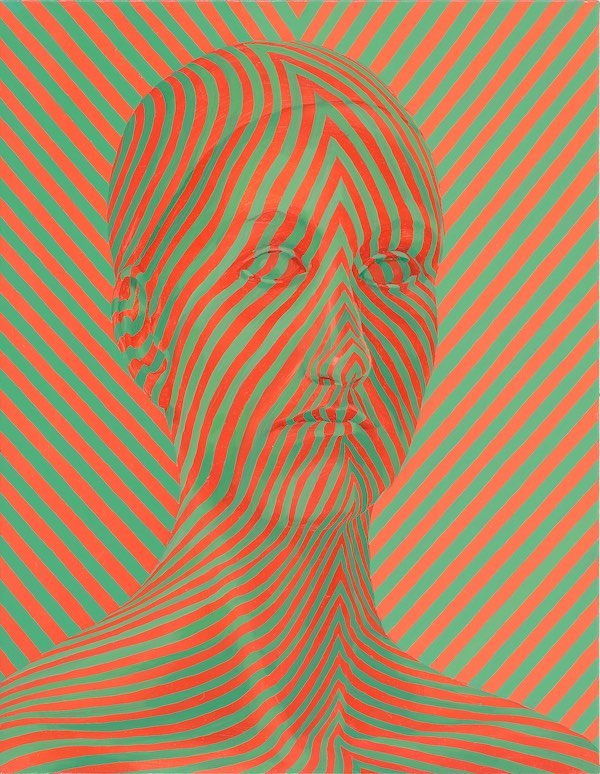

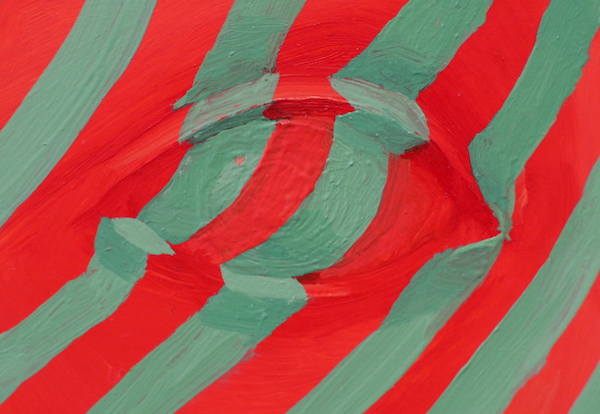

A subtle piece. I would argue that the strength of this work is that it is primarily a mental image realized through alternating bands of color rather than stripes mapped onto an objective structure.

Sascha Braunig, Chevron, 2012, oil on canvas over panel, 18 x 14 inches, Photo courtesy of The Collection of Niva Grill Angel.

Sascha Braunig, Chevron, 2012, Detail, Photo by Matt Mitchell

Like an apparition, Tabouret’s image feels specific for moments then becomes simply colors and shapes. In the headdress blue strokes of the same size, hue, and outline represent the essence of flower petals rather than their appearance in real space. The whites of the eyes are the orange of the ground, a darker shade than that around them. Throughout the work the paint treatment continues to be non representational in small unexpected ways. The structure of the face remains just simple enough that the whole remains in unreality.

Claire Tabouret , Makeup (bright lipstick), 2018, acrylic on panel, 24 x 18 inches, Photo Courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery

Claire Tabouret , Makeup (bright lipstick), 2018, acrylic on panel, 24 x 18 inches, Photo Courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery

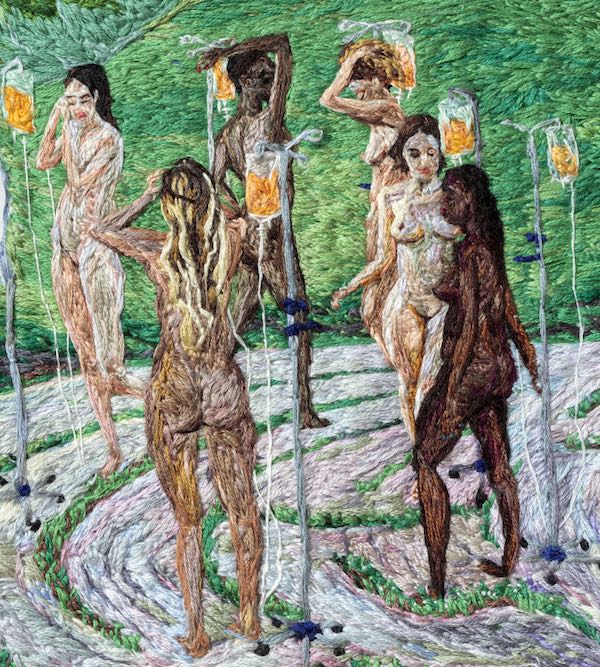

Here material dominates on other terms as Narrett defies limits, providing flesh tones and form development through color that should be the envy of any oil painter. Yet it is not about illusion as the character of the thread plays itself in cameos within the pictorial drama. String as string features in the giant red bow placed in a stretch of lawn, as it does also in the intravenous bags dripping orange juice(?) into the nude garden party denizens. Wherever Narrett’s figures are sourced from they are re-created in her work as if being embroidered is their best form of existence.

Sophia Narrett, Stuck, 2016, embroidery thread and fabric, 62 x 38 inches, Photos by Matt Mitchell.

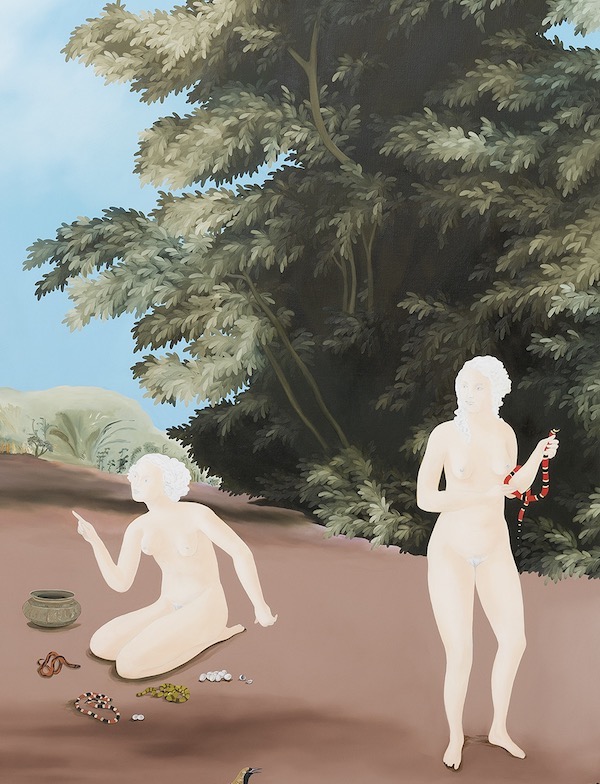

Khatibi manages to wield a rhythm of line as well as a conception of pose and action that makes her spectral traces of figures look like relocated citizens of art history. The landscape is a more assertive character with its lavishly painted stylistic trees and masterfully brief illusory sky.

Sanam Khatibi, Empire of the birds, 2017, oil and pencil on canvas, 78 3/4 x 98 1/2 inches, ourtesy of the artist and Galerie Rodolphe Janssen.

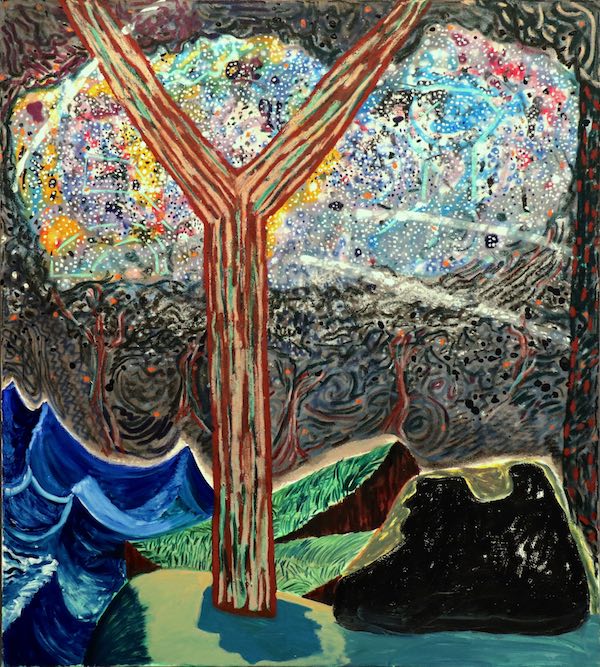

It is the enviable position of the plain air painter to be able to worship the natural world with devotion. Hughes manages to convey that same love through full on mental reconstructions of landscape as myth. Living cognizant of such fully animated vistas seems like it should raise her to a higher level of communication with the cosmos.

Shara Hughes, Milky Way, 2016, oil, enamel, spray paint, air brush and acrylic on canvas, 60 x 54 inches, Photo courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery.