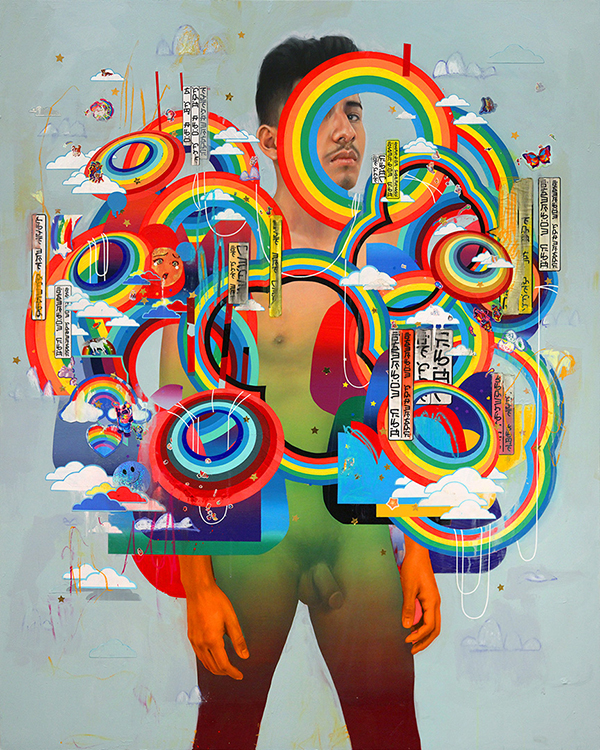

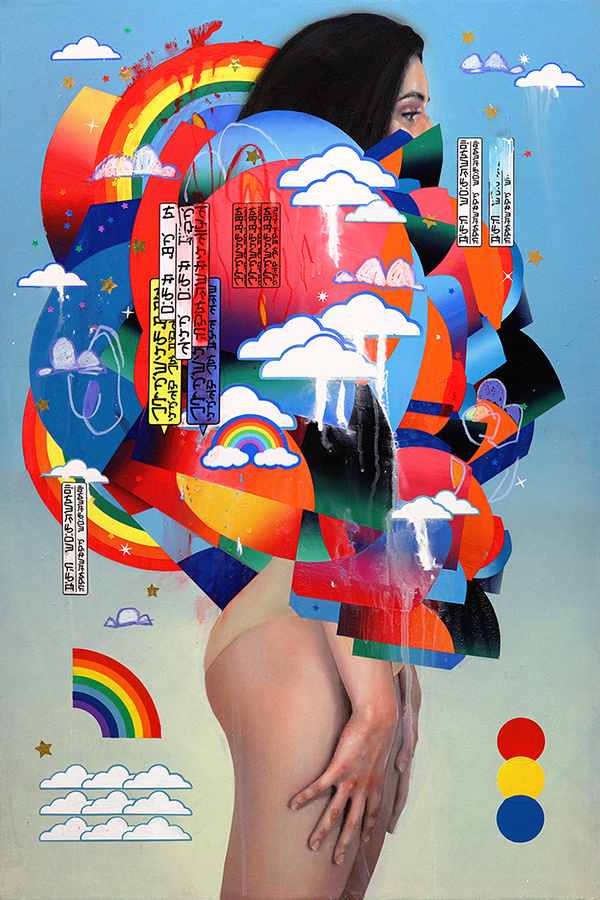

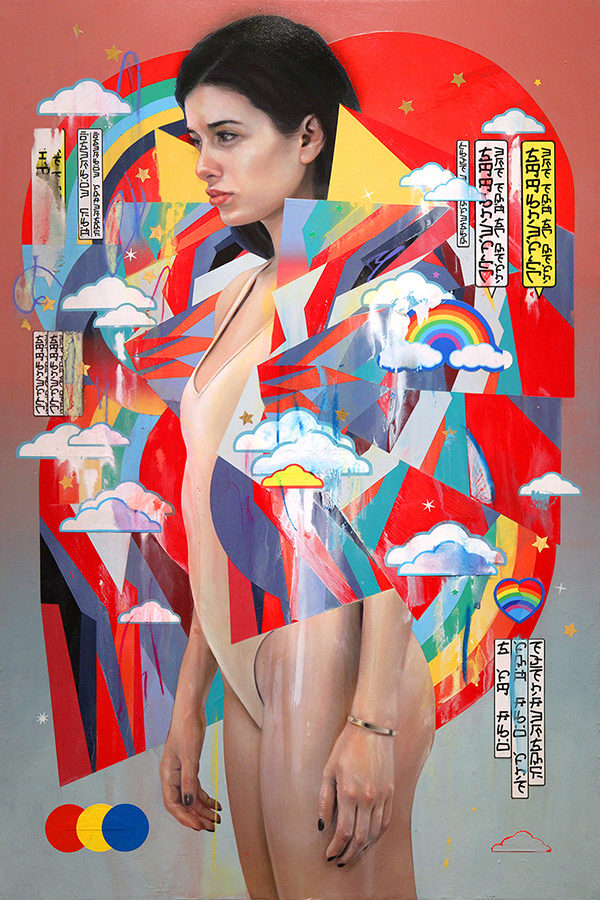

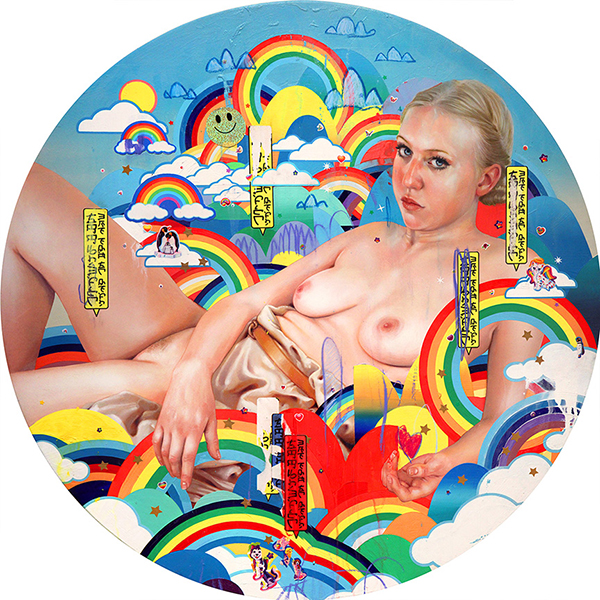

Who wouldn’t want to pose for a contemporary artist as talented as Erik Jones at least once? His ravishing paintings scream idol, perfection, and beauty. They also scream freedom, eroticism, and confidence. His models are literally covered in liters of paint – sometimes thick, sometimes thin, but always conveying the unbearable weight of perfectionism. For Jones, the human body is a medium between him and his audience and the effect of paint in a variety of textures and effects is a performance in and of itself.

Erik Jones has made an art out of the cutout – his subjects are hyper-realistically produced, each detailed and intense beneath a bath of paint, their nude bodies coated in reds, blues, and rainbows. Indeed, his subjects appear to be wandering about in a dream kingdom, and the clouds of color permit both reality and abstraction to coexist in a sea of fashion-like see-throughs. Jones depicts glamorous, divine Adonises and Venuses, their beauty pushing beyond their painted skin, asking whether they are mind or body à la Descartes.

Erik’s new series of work ‘Twenty Sixteen’ is currently on view at Jonathan Levine Gallery until April 30, 2016.

Did you only start working as artist in 2012 – at least, this is how I read your CV. What were you doing before 2012?

Yes, in 2012, that’s when I felt my work was moving towards a contemporary narrative. Before that I worked as an illustrator working in comics, fashion, and graphic design.

How has your past as illustrator influenced your transition into the fine art world?

When I first started painting and exhibition with galleries, I tried very hard to leave my illustration past clear behind me. But I found it was difficult to truly separate the two. I had acquired a following as an illustrator, and when I switched to ‘fine art’ I saw myself still working to keep that base happy. As I’ve grown more comfortable with my current work, I’ve stopped viewing social media as a form of validation. I try to not put the same pressure on myself if people don’t respond to a painting on social media platforms. What’s funny is that I now welcome my illustration work from the past to show through in my work. However, now I want to use the skills I’ve acquired as an illustrator to say something, rather than just to make something beautiful.

In your first works, you were obviously experimenting with realistic portraits, geometric shapes and expressionistic brushstrokes. Then what happened?

I’m not sure anything really happened. My current work still explores those basic elements. But I have been slowly focusing more on conceptual narratives along with my evolving aesthetic.

Your paintings have clearly been going through a gradual change, then one day not too long ago, you decided to mix up your figures with a kind of Japanese cartoon style. Tell me about this evolution.

I think I am actually making fun of myself as an artist – including all the fun bits about my past. This current exhibition where I stepped out of the box with stickers and graphic design elements actually fulfills more of a conceptual idea, so it’s not just for looks.

The sticker aesthetic is used to provoke an immediate reaction to the work. In this case, it’s nostalgia –for many people, I think. I wanted the viewer to have an immediate affection for the work. I purposefully used vintage stickers from the very late 70’s to the 90’s to trigger this reaction. Mostly incorporating Lisa Frank, Rainbow Brite and generic stars and sparkling smiley face stickers (smiley face stickers I actually made myself from glitter paper). This aesthetic is also used to put the viewer in a state of fantasy, so the stickers should theoretically complement the work.

Let’s talk about your subjects. Are they inspired by models from fashion magazines?

Commercial fashion photography has definitely influenced my work a lot. I find myself fascinated by the generic qualities of the models. They come off as non-offensive and kind of asexual (at least in the photos I gravitate towards).

Have the canons of beauty changed, over time?

For me, they have. I used to be interested in painting a pretty figure. Now I find beauty in all types of people and things. This will become more apparent as my work develops. I’m also not interested in only painting pretty people. I want the concept embedded within the painting itself to dictate if a “pretty person” is needed.

What does “beauty” mean for you? Is it a synonym of “vanity” or “status symbol,” or merely part of a commercial strategy?

My current view is that beauty is a representation of our time. I consider myself a contemporary painter, painting contemporary people. Beauty is part of a visual dialogue of what is happening now. It is vanity, it is status, and it is commercial. All of these things have context and meaning in my definition of “beauty” and in my work.

Does “beauty” ever get used to consolidate a certain socio-economic and cultural “superiority,” a kind of upper class cult from which whoever is either not beautiful or doesn’t embrace or worship beauty might easily get excluded from this “caste” or “sect”?

One could most certainly look at “beauty” that way, and of course, beauty has been used that way. But I look at beauty in a more unifying way, a way to communicate. It transcends language and politics.

Are you able to catch your models’ souls and inner beauty while portraying them?

Working with a model is a collaborative process, but what get from them is what is necessary for the work. To find their true “spirit” is not my priority.

What sorts of skills do good artists possess?

We are all so different from each other, as artists. To project my own idea of what a “good artist” should have knowledge of would be irresponsible on my part.

Has this interview allowed you to find out more about yourself?

Interviews are always helpful. They force me to state what I’m thinking and help solidify the chaos that’s in my head.