American painter F. Scott Hess has had a long and distinguished career as a representational figurative artist, carrying the banner for this often-belittled (by the fine art establishment) art form long before Beautiful Bizarre Magazine came into being. Now an Associate Professor at the Laguna College of Art and Design at Laguna Beach, California, in addition to continuing his own artistic practice, Scott has been a beacon and influence for lovers of realism and the figure in art and a true figurehead of the movement. Over his career, Scott has garnered many awards and is represented in the permanent collection of many gallery museums in the US and around the world, including the Smithsonian Institution.

Please enjoy this intriguing interview with Scott by Natalie Holland of Poets & Artists. In addition to being a frequent contributor to Poets & Artists, Natalie is herself a talented and lauded figurative artist, having had works displayed at London’s National Portrait Gallery and the Royal Society of Portrait Painters.

Scott teaching at Laguna College of Art and Design – photo by Carol Covarrubias

Scott teaching at Laguna College of Art and Design – photo by Carol Covarrubias

Scott Hess was born in Baltimore in 1955. His family moved to Sarasota, where his parents divorced when Scott was seven.As a response to that, he started making a series of bondage drawings. He didn’t realize at the time that those nude bound women represented his mother, who he was trying to control. Little did he know that the erotic drawings he created out of personal psychological necessity marked his birth as an artist.

Scott got his BSA in Fine Art from the UW-Madison in 1977. The painting department was primarily abstract, so he stayed with drawing and printmaking where he could do figurative work. His desire to learn to paint brought him to the Academy of Fine Art in Vienna, which he attended from 1979 to 1983 in the Meisterschule Rudolf Hausner. There, he had his first solo exhibition at Galerie Herzog, 1979, and thus started making a living from art.

Looking back at his artistic career, he reflects upon the driving force behind his creativity.

“You can’t control the world, but you can control what goes onto your canvases. In the studio I am a god. And like any god what gives you the most joy is bringing the creatures you are inventing to life. I especially like developing the psychology of the people in my paintings, delving into what makes them tick, and expressing their interactions visually. People have always been at the core of what my work is about.”

Despite being a god in the studio, the process of creating art doesn’t usually makes him happy. Scott simply doesn’t think the enjoyment is the goal; painting for him is pure grunt work.

“I often come into the house grumpy as hell after a full day in the studio. What painting does give me ultimately is a sense of fulfillment that is greater than anything else I’ve done in my life. That said, the anticipation during planning a work, and the first half of painting it, are more enjoyable than the second half where I have to polish and perfect the image. The work never turns out to be quite as wonderful as it was in the initial vision.”

Scott works at the large two-car garage attached to his home.

“The space is ugly and raw. My studio is a mess, there is stuff everywhere and chaos reigns. This rarely bothers me. When I’m working my consciousness slips behind the picture plane and stays there as I paint. I clean up the studio when I have visitors because they’d otherwise be disgusted.”

He doesn’t have a favorite tool, or color, or brush.

“I have a limited number of artists’ materials that I need to make my work, but I need it all to accomplish anything. There’s nothing exotic about any of it, just colored muds, sticks with hairs glued on the end, and some woven fabric support. Making paintings is like alchemy: you turn mud to gold.”

However, turning mud to gold doesn’t mean that the result will be a pretty picture. Scott doesn’t aim to please, he doesn’t want to decorate your house or put you at ease.

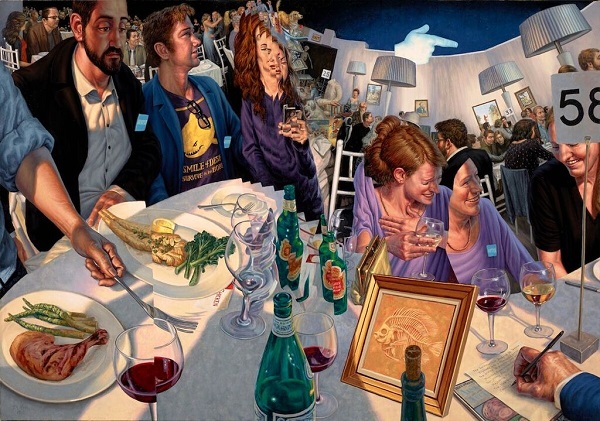

“I think I want you to feel compelled to love my work despite being deeply disturbed by it. Human emotions and psychological issues are messy and complex beyond belief. We are attracted to our own odd desires, often unwillingly, and I like finding that edge between attraction, repulsion, and obsession. I find my works beautiful, but I know that over the years a lot more people are freaked out by my paintings than share my sense of beauty. But when you do find those people who share it, you’ve connected to a kindred soul.”

Although sometimes current social or political issues find the way into his work, the true source of his inspiration is his own experience of life.

“Usually the content has more direct links to things like relationship issues, parenting and family, ageing and mortality. These are timeless and universal concerns that get filtered through my unique experience of them. Political work often has a short lifespan so I tend to avoid it, though I might add some things that I find humorous that connect to current affairs.”

Indeed, he did put Trump and Hilary Clinton into a show piece he created using his own students and professional models.

With the career that now spans more than forty years, there have been many milestones that Scott recalls, and one exhibition in particular.

“My most popular exhibition was The Paternal Suit: Heirlooms from the F. Scott Hess Family Foundation. It was an exhibition of 102 objects that told my missing father’s family history since 1634. I had to invent the artists and artifacts they made to tell that story and use every variety of skill that I’ve ever acquired to do it.

The exhibition traveled to five museum venues, mostly across the Southern United States. It was a success also because so many museums don’t want to see skilled representational painting hanging on their walls.”

Another milestone was his sixty painting retrospective at the Municipal Art Gallery of Los Angeles in 2014. The show went on simultaneously at Begovich Gallery at Cal State-Fullerton, and although the retrospective didn’t travel anywhere, Scott was proud of a four decade span of work, followed by the book that is available on Amazon.

Apart from successful exhibitions, he finds that survival as an artist can be tough.

“Besides the highs and lows of art world attention, there is a financial hurdle that many find insurmountable. You have to realize that this career has some wonderful high points, where the money flows and everybody seems to love you, and incredible lows where you are broke and nobody gives a shit about what you do. Add a family of four to the mix, and mortgage payments, and all the other expenditures of life, and it can get scary as the bank account dwindles. I am lucky my wife has been very supportive and has an innate sense of frugality. As a family we were never wasteful, drove older cars, and lived modestly. Somehow we got through it, the kids are grown, and life at the moment seems pretty solid.”

However, Scott finds that the hardest part of being an artist today is actually making something that people are interested in.

“Your first job as an artist is to get a viewer’s attention, and if you don’t you’ve failed. It’s over. Today there is such a glut of imagery, a daily online inundation of paintings, drawings, and photographs, that rising above that tide is a feat in itself. Then, having their attention, how do you hold them, give them a deeper experience or something to ponder? Things seem to be moving really fast in our hyper-technological world, and as an artist you have to adapt to that new reality in some fashion -or risk being irrelevant.”

Despite acknowledging the importance of presence on-line, Scott doesn’t have a personal website – because he simply hasn’t found he needs one. However, having said that, Scott does consider the Internet a useful and necessary tool to search out new opportunities.

“I post on Facebook and Instagram, and have Twitter, Tumblr, Ello, and Linked-In accounts; Poets & Artists has published a fair amount of my work over the years. I realized that a lot of things have happened in my career over the last ten years that simply would not have occurred if I’d not been posting online. It is logic: if you post, then opportunity knocks when it sees your beautiful door. If you have no door, opportunity passes you by.”

He adds that being of an age and having a long record of shows imply that most opportunities seek him out.

“I get invited to participate in quite a few group shows every year, solo shows seem to come along when needed, and museums are acquiring works here and there. I’ve also have had a hand in training a whole generation of figurative artists. I enjoy helping them out when I can and recently curated a couple of shows that included a group of former students mixed in with established artists.”

When it comes to the business side of being an artist, Scott admits that he has never been very good at it.

“I think to be really highly successful, at a Jeff Koons or Damien Hurst level, you have to be 95% businessman, and 5% artist. If you enjoy business, then I guess that is fine. I just enjoy making my paintings too much to pay greater attention to the business side of the equation. I do just enough business to keep it viable.

It used to be the interaction with the galleries, curators, and critics that took up your time, but that seems to have lessened as the amount of time spent online has increased. I hate Instagram, because I think it is cheapening art and influencing the art that is made today. I think of Instagram as a necessity, just like trying to find a gallery once was. Both actions had some very unpleasant aspects, but you hold your nose and do it.”

By the end of the interview, Scott has been asked to name his favorite work, and he chose his current piece that is based on a dream from 1978.

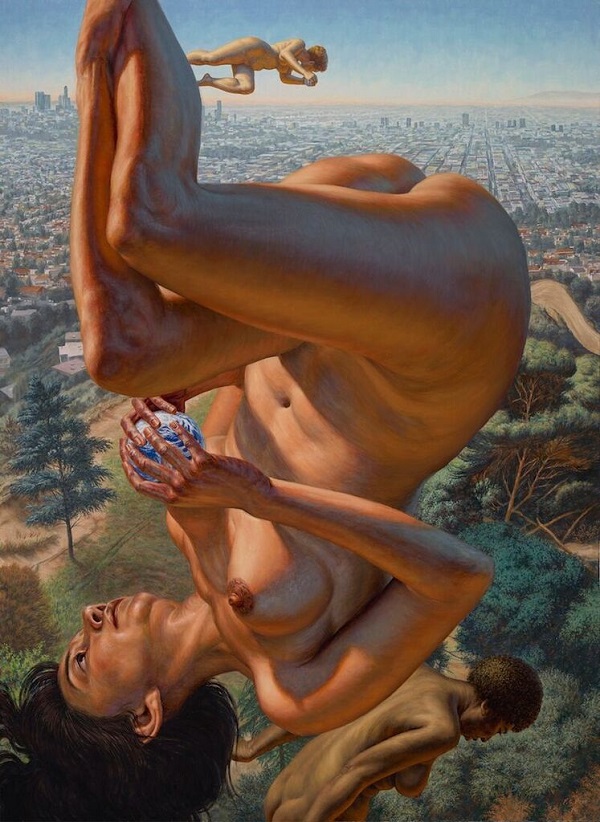

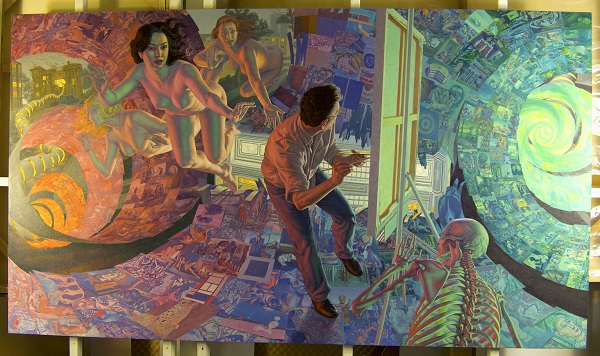

“I was sick, with a high fever, and dreamed that the history of art was coming out of our second floor toilet, like a giant mummy-worm full of paintings and sculptures. It rumbled down the hallway, out the door, and down the highway. Suddenly I was caught up in the history of Art, and it was horrible. I was wrapped up with a couple of paintings that had made me famous and was bouncing uncomfortably down the highway when the history of art was struck by a Cadillac Eldorado. I was blown out of it into a nearby ditch, and as I lay dying my last words were, “Thank God I’m not in the History of Art anymore!” I woke up then, and 40 years later I am making a painting about that dream, my legacy, and my own mortality. It has the spiral of art history, which is not unlike the daily cascade of online imagery, and some muses or guardian angels flying in around the breach of the Cadillac. The three women are nude because I don’t know what guardian angels wear, and one of them seems to want to ward off death, the skeleton figure to the right. There are thousands of little images from art history.”

This canvas has taken him the better part of a year to paint.

“In the studio I am a god – and like any god what gives you the most joy is bringing the creatures you are inventing to life,” -F. Scott Hess, the artist

Interview courtesy of Poets & Artists