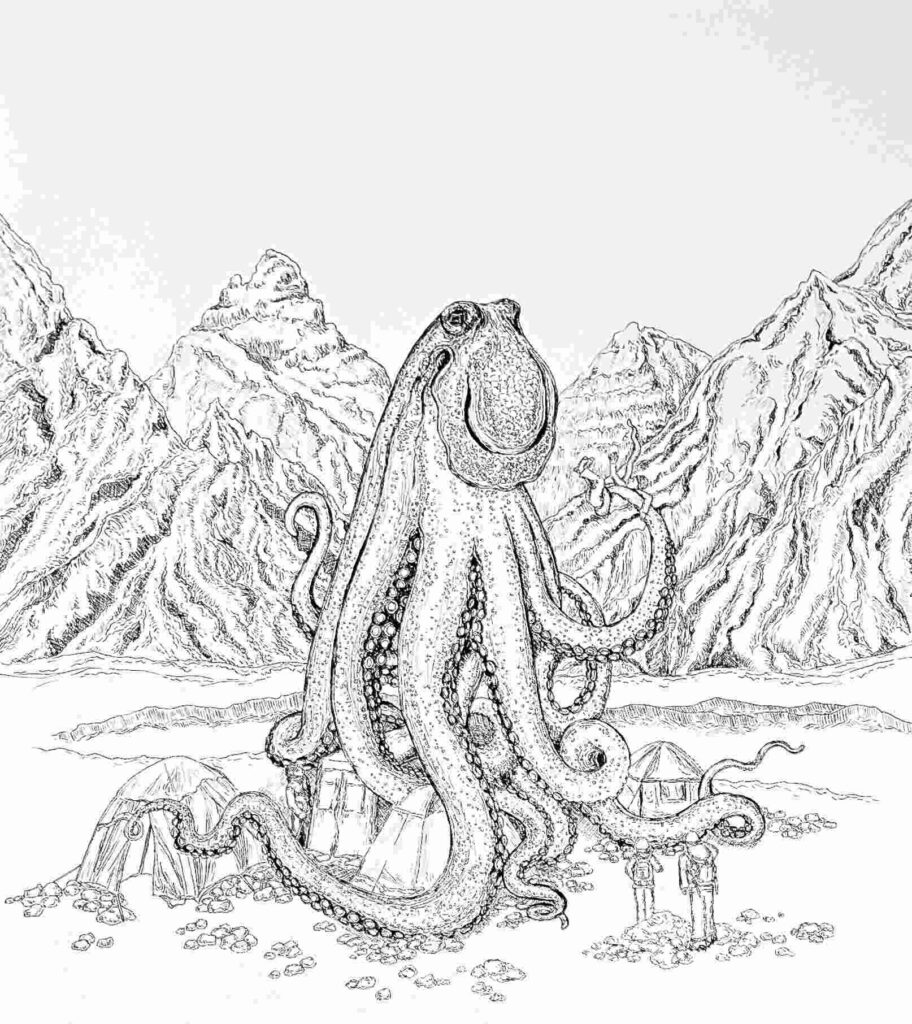

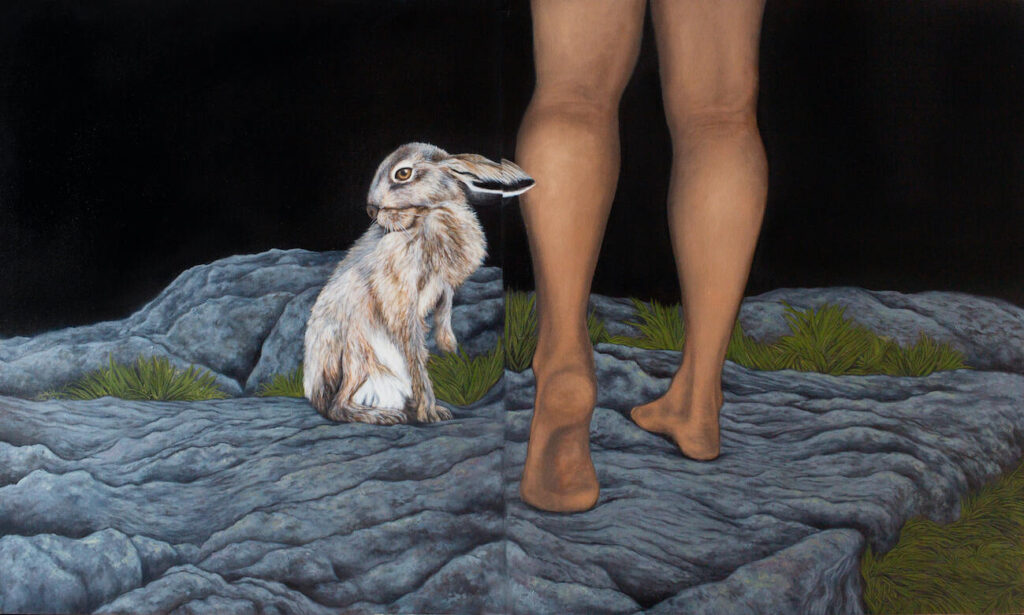

Laura Thipphawong’s paintings are what dreams feel like. She takes those feelings of wonder and confusion that the subconscious mind grapples whilst in an unconscious state and presents it before our conscious minds. Nature, horror, sexuality and folklore are all complex themes of research weaved into every canvas, creating dreamy, or sometimes nightmarish, surrealist landscapes.

Viewers are encouraged to connect, admire and dissect each piece, delving deeper to discover hidden meanings contained within each canvas. Laura’s work is sure to stir feelings within anyone as she disturbs the comfortable and comforts the disturbed.

Laura Thipphawong is a painter, writer and historian who is best known for her surreal artworks that feature complex topics and symbolism. Originally from a small town in north Ontario, Canada, Laura is a self-taught artist who has been painting in her chosen medium of oils since she was twelve-years-old. In 2016, Laura graduated from OCAD University, Toronto earning herself a BA in Visual and Critical Studies with a minor in Drawing and Painting before going on to complete her Masters in History of Art at the University of Toronto in 2018.

Laura’s artistic work ties heavily into her interest in researching complex narrative symbolism of the psyche including themes of sexuality, horror, folklore, literature and natural science.

Part of being alive is pain, distress, confusion – so I think that even if a work of art is beautiful or depicts something beautiful, if it’s really soulful and authentic it should have something odd or uncanny about it, and that’s what make it great, that’s what expresses the human condition.

Interview with Laura Thipphawong

You did your thesis on death and the maiden imagery throughout art history. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this art motif. What made you want to pursue this as a body of research and how it has influenced your creative work?

I’ve always been interested in horror media and the themes and archetypes within it, and before there were horror movies, there was horror art. Death and the maiden was particularly interesting to me because it involves so many layers of subtext, and as an image it’s evolved in such interesting ways over the centuries. To sum it up, the man signifies death, and the woman signifies life, but not literally. They were allegories of life and death, but more recently life and death became metaphors.

For example, I argue that The Anatomist by Gabriel Von Max is a death and the maiden image, where the man represents death through the scientific violation of the body, and the woman represents the changing meaning of a woman’s role, or the changing idea of a passive or submissive woman. These kinds of concepts are inspiring to me on a symbolic level in my art too, so it was great to research these things academically and then also paint a series about it.

Your series ‘The Maiden and Death’ was inspired by 18th and 19th century European literature. Which pieces of literature inspired this body of work?

Goblin Market by Christina Rosetti was a huge inspiration to me. It’s the story of two sisters who try the fruit that’s being peddled by goblins. When one sister eats the fruit, because she very much wants to, suddenly she starts to wither and has become essentially doomed or tainted for having eaten it. In most analytical critiques about the poem, you’ll see a lot of focus on Goblin Market as a redemptive story and of the power of sisterly love.

That is for sure one of the themes, but for me, I see it as more of a story about women who act on their sexual desires and are then rejected by society for it, even in a society that constantly sexualizes them.

Christina Rossetti had once volunteered in a Magdalene Asylum, where they housed and often abused women who worked as prostitutes or women who were known to be sexually active or even just sexually suggestive. It’s been centuries since her time, but we’re still doing this to women, sexualizing them but chastising them if they are found out to be sexual. So, my series based on my thesis research was all about the tricky navigation of the sexual experience for girls and women, and what it means for us to not just be passive in sex and romance. My painting ‘Fallen’ was directly inspired by Goblin Market, and the idea of the infantilized, sexual, sexualized, and “fallen” woman.

Which periods are you drawn to most when researching art history?

I love the Victorian period. I love the aesthetic, the clothes, the furniture, the massive changes that happened alongside so many pivotal inventions, and the art and literature that came with it was so much more driven by imagination and emotion than the periods before it.

Alongside being a practicing artist you are also an avid researcher. Does your research inspire your art and vice versa?

Yes, definitely, as I mentioned, ‘The Maiden and Death’ was an art series inspired by my thesis, but I’ve also done research on things like the trope of the mad scientist in horror media, which was inspired by my love of incorporating images from natural science into my artwork. I’ve also written some essays on existentialism, which spurred me on to paint a series called ‘Parallel Universe’, which is about the body and the perception of experience in place and time.

You incorporate various themes into your work including sexuality, horror, folklore, literature and natural science. How do you approach tackling and intertwining these themes into one cohesive work?

I have to trust my gut with these things. I used to think that I shouldn’t do work that’s too multifaceted or that I shouldn’t try new styles or subject matter because it might be too obscure to people or that it wouldn’t work to create a “brand”. Some art directors or gallerists don’t want you to experiment or be too esoteric, that’s definitely true, but I can’t let that dictate how I want to express the things that are important to me. Also, I think that the subjects that inspire my work fit well together without even having to try.

There’s a sweet spot in art, whether it’s paintings, movies, literature…where it can work on its face without having to analyze it or know the context, but when you do, it’s all the more rewarding. I want my paintings to be accessible and enjoyable on an aesthetic level, and then for anyone interested in the deeper meaning, there’s a whole other level to uncover.

Who inspires you and why?

That’s actually kind of a tricky question, more so than you might think. I’ve been inspired greatly by people in my past, but let’s say you had someone who was your muse, what happens when that person is no longer in your life? That can be really difficult. It’s impossible to separate art from my personal life, but I try to evolve the way I make art as I grow and make changes, otherwise I’d be stuck in unhealthy situations and never move forward. So now I cultivate ways to be inspired that don’t involve other people. Getting out in nature alone inspires me.

Spending time just thinking aimlessly can be very inspiring, especially if you’re hiking or paddling over a long period – I find that’s a sure-fire way to shake loose the ideas that will start to come together to inspire what I’m going to do next, so I try to prioritize that.

I’m also really inspired by movies and TV. I’m kind of obsessive about it, but it’s more than just zoning out and watching whatever’s on; it’s always been a huge source of comfort for me. I’ve titled several paintings after quotes from movies and TV shows that I love, something like The X-Files, which I often have playing in the background for hours while I paint.

I understand that you have done research on horror symbolism. Can you tell me about your research into this subject and what you have uncovered thus far?

I mentioned my research on the mad scientist trope; it’s not a comprehensive survey or anything, but I did write a paper and presented it at a conference in Washington DC about how the trope was borne out of The Enlightenment and reflected in art and literature and now lives on, especially in movies. The mad scientist is a reflection on the cultural anxieties about the secular body, in other words, the human body being untethered from religious or spiritual association once a person is dead.

This was the idea that scientists brought with them when dissection was introduced as a regular and legitimate practice, and autopsies, and x-rays, and so many huge advancements that sort of compartmentalized the body, and people weren’t used to thinking like that. People still have trouble with the idea of organ donation. And scientists were excited to push this on people at large, sometimes for their own glory. Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll, Dr. Moreau, these are good examples of the originals, but they’re still relevant and you still see iterations of the trope in contemporary media, and I’m very much inspired by all of that.

I want my paintings to be accessible and enjoyable on an aesthetic level, and then for anyone interested in the deeper meaning, there’s a whole other level to uncover.

As an avid lover of horror and unsettling art I particularly resonate with the phrase “art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable”. Is this a phrase that resonates with you?

Yes, 100 percent. Part of being alive is pain, distress, confusion – so I think that even if a work of art is beautiful or depicts something beautiful, if it’s really soulful and authentic it should have something odd or uncanny about it, and that’s what make it great, that’s what expresses the human condition. Strange and unsettling feelings are part of the human experience, and they’re part of every individual, but people will often discount horror if they feel like the creative expression of the abject is depraved or low brow.

The abject, the obscure, the scary stuff…they’re a big part of life, and dismissing that because at first it makes you sort of uncomfortable is not just narrow-minded, but it’s also really boring.

What do you think it is about unsettling art that appeals to the human psyche? And what do you think repels some people from it?

Cultural standards are really bad for dismissing the quality of horror in art and especially in movies and TV. I hate the term “elevated horror” because there’s always been good quality and bad quality horror – good horror is not something new that has elevated itself above a low-lying genre. Take The Silence of the Lambs: It drives me crazy when people try to say that it isn’t a horror movie. Of course it is, but people want to recontextualize it as strictly a thriller because it’s so amazing and a multiple Oscar winner, it couldn’t possibly be a horror movie, but it is and it’s one of the greats.

Horror and unsettling art has always been a lot more accessible than people realize. According to a study by Dr. Deidre Johnston, there are four types or horror viewers, and it’s pretty much focusing on narrative film, but I would equate it to all types of horror media. It would take too long to go into the nuances of each type, but I find that one of the types is pretty easy to understand and probably pretty relatable, and that’s the thrill watcher, someone who is sympathetic or empathetic to the victims, and finds it cathartic to feel the rush of danger through them as a conduit.

Another type, the one I relate to, is the independent watcher. It’s a lot like the thrill watcher, except you also gain a sense of personal empowerment for facing the fears. I feel like there’s another level to this one, speaking from my own experiences, where you might also feel validated. If you’ve been through horrific things, or even if you just have a preference for strange aesthetics, or if you just love monsters, then seeing those things in art is a reflection of you and your mind, and that is comforting.

Do you have any new projects on the horizon that you can tell our readers about?

I do have a couple of things in the works. I have a solo exhibition coming up of paintings that revolve around the history of natural science and people’s relationship to animals. That will be in the Rotunda Gallery in City Hall in Kitchener, Ontario, in winter 2024. I also have two shows tentatively scheduled for this summer with Gagné Contemporary and Walker Contemporary Art in Toronto.

The curation of these shows hasn’t been done yet, but right now I’m working on pieces that I’m really excited about; they’re large-scale oil paintings on unstretched canvas, and the process and presentation is a lot more raw and instinctive than what I’m used to, so I’m looking forward to evolving as an artist through this new work.