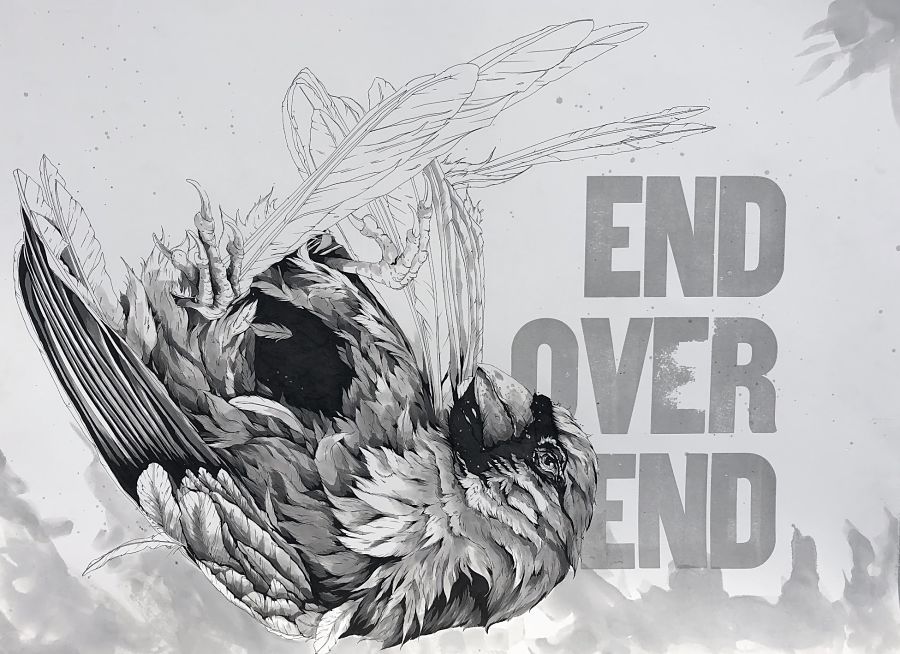

In a world saturated in colour the simplicity of black and whites can be overlooked. Tones of white, grey, and blacks can be equally effective as bright colours; black and white can portray warmth, life, and texture with impact colour sometimes diminishes. Alexander Landerman creates works that appear drenched in colour and life despite animal corpses being the primary sources of inspiration and not a drop of colour making its way onto the page.

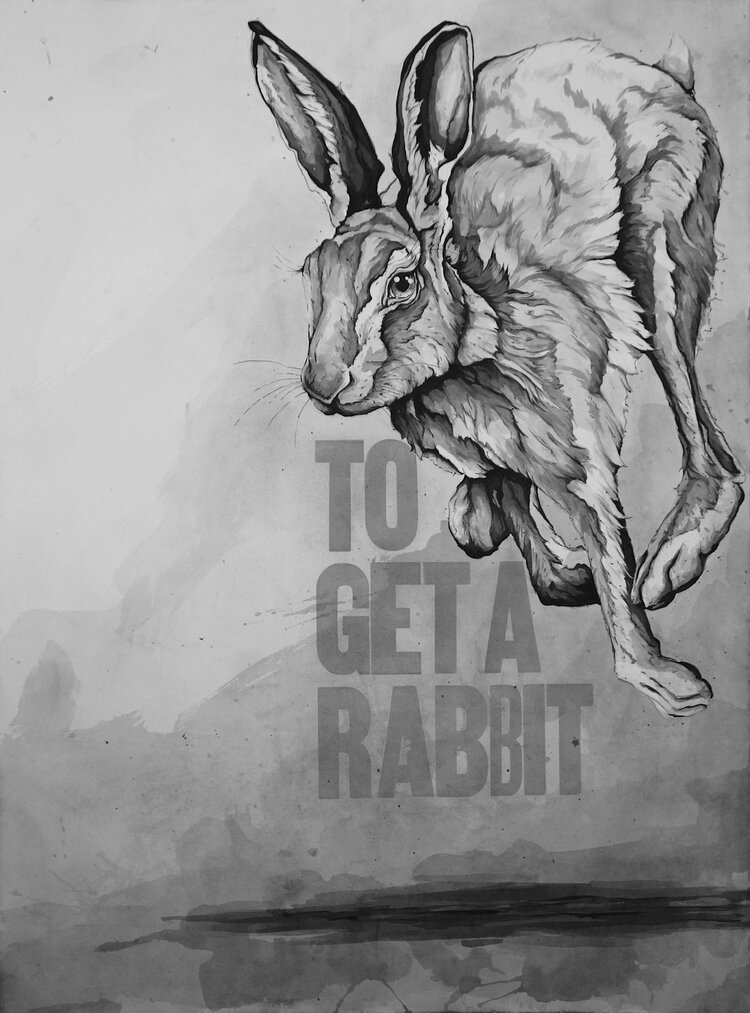

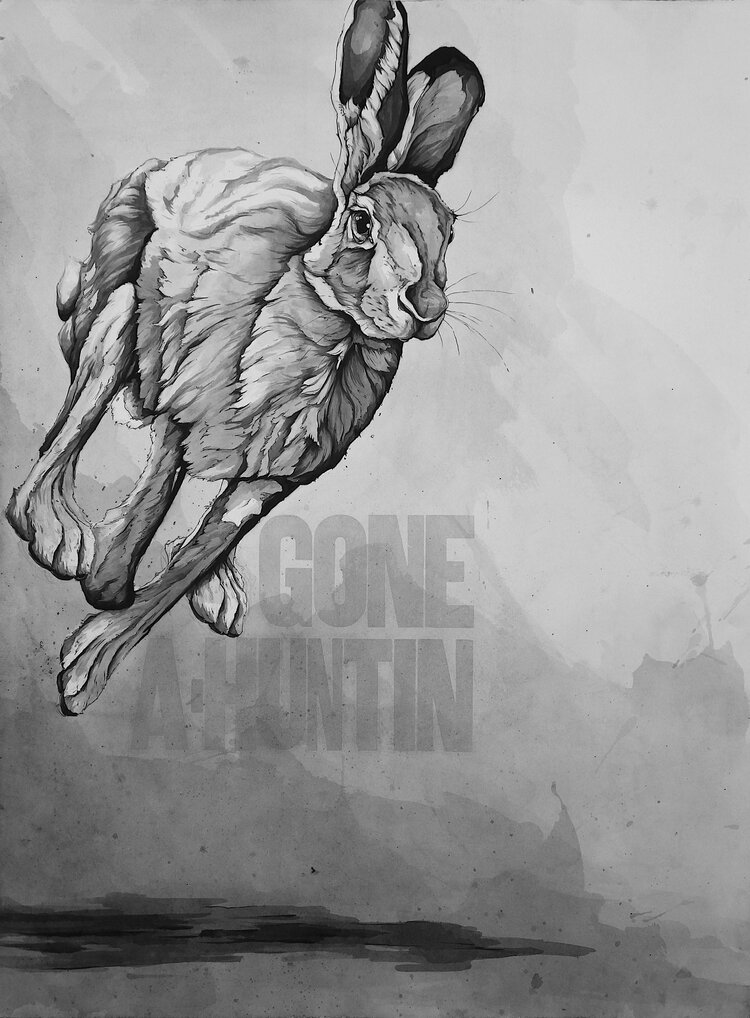

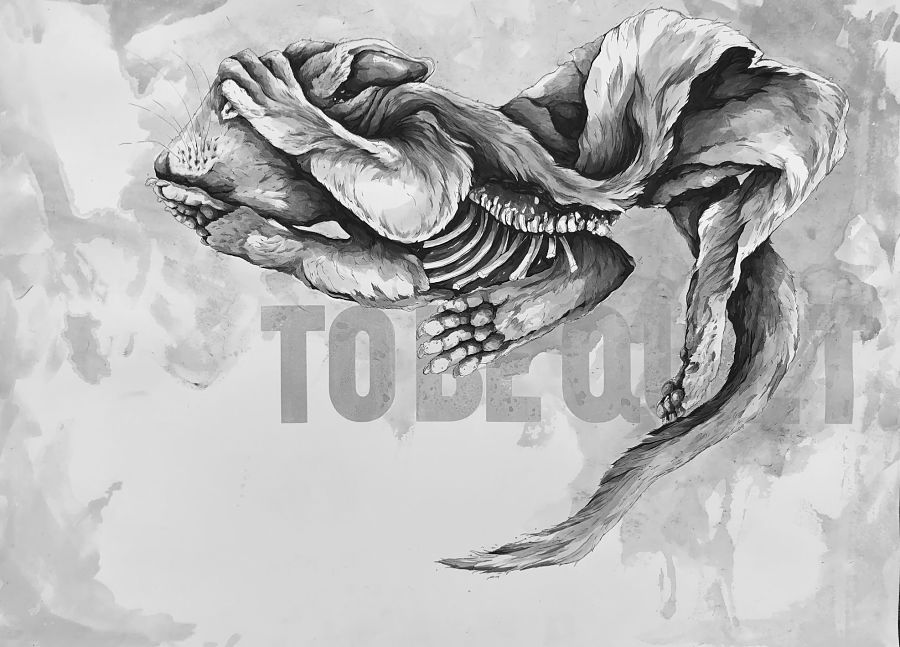

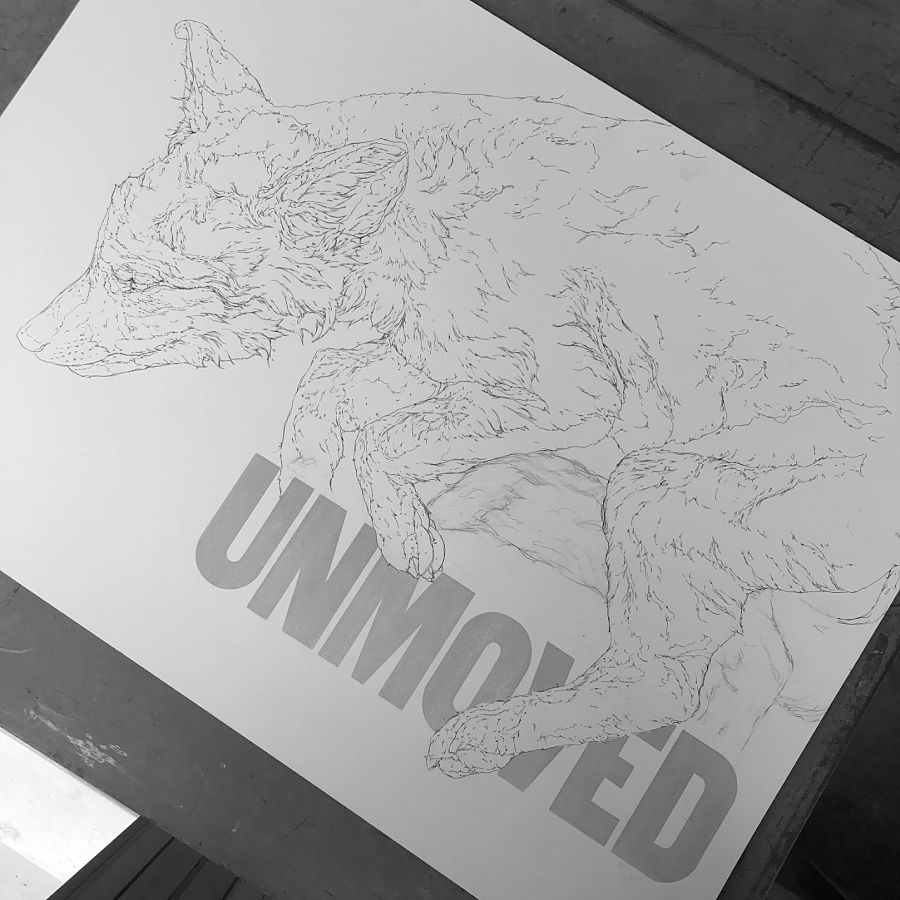

Layered and weaving in and out of Alexander’s wildlife are words and phrases using traditional letterpress methods, a more tactile and impactful method than adding text through a computer. A skill Alexander honed at Indiana University and has moved on to teach to a new generation as a faculty member there.

It is this combination of old-world printing techniques and careful anthropomorphized illustrations that encourages a connection between the viewer and the subject.

Through suspending the subject in moments of tension, I subtly push feelings of discomfort, apathy, aggression, or fear on the viewer. Encouraging them to question the level of understanding possessed by animals and their potential role in society.

Interview with Alexander Landerman

Could you please tell us a bit about yourself, where you grew up and what were some of your early creative influences?

I’m a letterpress printer, illustration, and educator, living in Bloomington, Indiana, teaching letterpress and design.

My Grandmother was a home economics teacher and single mom that was one of those people that knows the name of every flower and tree. She had an interest in high-quality crafts and arts later in her life. I spent a lot of time with her being exposed and influenced by different aspects of nature and art. I grew up in rural Wisconsin, right in the middle of Wisconsin, on the outskirts of a rural town. I was extra lucky to always be surrounded by nature and being encouraged by my parents to be creative and exposed to art. I struggled academically as a child but my father always encouraged us to focus on doing things that make you happy not money. Without this, I don’t think I would have ever gone to college let alone into higher educations and making the art I do.

Living rurally, I was constantly exposed to nature, there was an elk farm down the road where I use to climb in with them and run around. My father’s side of the family has always been involved in hunting, fishing, and trapping as a young kid in a rural area and in a small community I wanted to be part of this but I couldn’t kill them. I don’t know why I have lots of theories but I think it was empathy for them and perhaps that’s what affects my art to this day.

I guess I spent a lot of time alone and drawing was my way of communicating.

I, now, work as a faculty member at the Indiana University running the Letterpress Studio and creating work that combines traditional drawing techniques with emerging digital practices and letterpress printing.

How do you progress from an idea to a work? Where do you get your ideas from?

I think you’re always going to have more ideas than you are able to actually produce, but being in wild spaces really helps. The series I’m working on at the moment started when I became fixated on animals and the way we see them once they die.

I had drawn a dead rabbit and was exhibiting it when someone approached me and told me how much they love my work, but wished I wouldn’t draw dead animals. They asked why I drew it. And I replied, “I found this rabbit dead in my yard after getting hit by a car.” And the woman who was much older said, “I’ve lived in Bloomington, where I live for 2050 years or whatever, a very long time. And I’ve never seen a dead rabbit. I’ve never seen a rabbit hit by a car or roadkill rabbit.”

I didn’t want to argue with this person but I also mentioned I see them every once in a while while she continued to deny it. After that, whenever I went for a run in the morning, I would photograph all the dead rabbits. I completed this big drawing with every dead rabbit I found… about 50 rabbits. It built into this body of work where I just can’t stop thinking about how an animal that we really relate to or find a lot of empathy for or attach cultural significance to, like an owl or a fox, magically lose their importance when they’re dead.

They’re not visible. When something dies, we treated it as so much less.

A lot of my current work has been inspired by going on hikes with my partner. When we’re in the woods, Lou is looking for plants, animals, or plants and fruits and mushrooms and mycelium and all this cool stuff. And I’m looking for dead stuff.

This past year I found a flying squirrel, which will be in an upcoming show that I was really excited about. I found a possum that was really beautiful. I found a lot of deer. I found a fox. I mean, I find dead animals, and I just think they’re important when you find them. I take photographs. Lots and lots of photographs from different angles.

I like talking about the things that are happening in my community right in front of me. I feel that sometimes when you’re really specific, you can reach more people than when you try and be a lot broader. I want to focus on my experiences. Every day I run and I find another dead rabbit. This is my experience. Every time I walk my dog, I see this heron that is trying to carve out an existence on an incredibly small body of water that has 40 miles an hour traffic on each side of it.

And it’s less than a block, like a city smaller than a city block. And this heron built a nest there. I made a drawing that was this heron, very confined. I think other people have experiences where they are constantly confronted with dead animals on the side of the road or constantly confronted with an animal trying to exist in a space where it’s not really evolutionarily prepared to exist.

Are the photographs you take and your finds in the woods your main source of reference?

I’m not a photographer by any means. So I supplement my inability by taking a lot of photos. I have a telephoto lens, nothing fancy, but I take as many photos as I can.

The heron by my house, for example, I photographed the heck out of and made a drawing out of it because it was accessible. And my dad still traps. I’ll go home for Christmas, and he would offer me the chance to photograph a beaver or something else. Last year, he sent me a bunch of hog skulls.

There’s also a huge amount of resources at the University. It’s a research institution and I’ve been working with somebody in the biology area. It’s really important that all my drawings are either anatomically correct or augmented in a way that is intentional. I want my understanding of those animals to be equally as accurate. I want to be able to describe those animals in a way and identify those animals in a way that does justice to what they are.

Can you explain to us your process?

I start with the drawing and then pair it with the words. My partner and I will sit and brainstorm words when I’m in the type shop. We’ll come up with things that might work and write them down. I have a Google document that has hundreds of little phrases or single words that could fit with anything but feel meaningful.

The drawing starts as a pencil sketch that is built out of a combination of sketches I’ve made in a sketchbook. Then I will do it full size and then ink it with, like, a felt tip marker, so it’s outlined and is reminiscent of a colouring-in page. When it gets to that colouring-in page stage I bring it into the type shop and apply the letterpress. Letterpress printing is literally pressing letters against paper with ink in between the two; it’s pressing letters, which is the lovely thing about the name.

I have a masking technique that I used to allow the illustrations to interact with the type so the illustrations can weave in and out of the letters and interact with it on a different level, it’s a newer technique I’m working with.

When did you discover letterpress and start weaving it into your art?

It was in my undergraduate studies when I was studying toward Bachelor of Fine Arts in 2-Dimensional Art at the University of Wisconsin. I met this woman, Karen Heft, who is just an incredible person. She recognised that I was interested in letterpress and I didn’t mind getting dirty, which is part of printing.

She needed help in her studio. She’s an older person, and I was young and eager. We came up with a deal where I would come in at eight in the morning and work until noon. She’d give me lunch and after I could do whatever I wanted. It was a work exchange. She’s very smart and could proofread things for me; she helped me learn basic typography. She’d also look at the drawings I was doing and combining with text, and be really brutal in a beautiful, honest way, she would tell me if things were bad. If I asked why she wouldn’t always know the reason but she would talk me through it and made me into a better artist and illustrator. It’s thanks to her that I am where I’m at now because letterpress is why I got the job in higher education. There are not many people specialising in it. And I know enough to fix the presses.

I really struggled academically. I have some learning disabilities, and I still struggle to read. Reading can still be difficult, and I couldn’t read as a kid. I fell in love with illustration and drawing as a way of communicating.

Every kid wants to express themselves, but if you can’t read and write, what do you do? I learned to draw.

As I got older, and started to understand what was going on in my brain and why I wasn’t able to read, I was able to teach myself to read better. I fell in love with letterpress because it was like it was this seductive and beautiful thing that I could never do. But if I thought about it like drawing, it made sense. It felt more like drawing than writing to me. If I press a button on my keyboard to create words it doesn’t make sense but when I’m moving physical objects around in a press bed, it feels like drawing to me. That made it make sense in my head. It became really attractive because it was this thing I was so bad at, bad at for so long. To gain a little bit of control over it was really alluring.

It’s interesting to hear you say that. Viewing your artwork and the use of words and phrases, I would have assumed you were a reader. That words were important to you, but instead drawing is your primary form of communicating?

That’s really interesting. Words are really important to me because they are the thing that, as a child were the most detrimental thing to me. The thing that led to getting bullied and destroying my self-confidence. You can only feel like a bad student for so long or do poorly in school for so long before you start feeling like you’re dumb. Thank goodness I could draw just enough.

Or, at least, I was probably average at art as a kid, but because I was average at it, I was like, the fucking best! It’s the only thing I could do. I took it and ran with it. In a roundabout way that got me to letterpress printing and using text. And that’s why I like graphic design. Because I’m not looking at the words on the page I’m looking at the shapes on the page, and I love them.

Are you restricted in the fonts you use? Are new fonts being developed or is what we have it?

Wood type is still being cut. A company called Virgin Wood Type is cutting typefaces, some of which are being designed. And then there’s Hamilton, which is in Wisconsin, and still cutting and producing typefaces just in a much smaller quantity.

Where I grew up I was perfectly positioned to start illustrating animals and fall into the letterpress community, I guess it was natural that I would weave the two together. The type of wood that grows around the Great Lakes is really dense and therefore good for cutting and producing wood type. The person behind Hamilton started their foundry in Two Rivers, Wisconsin, and took over the industry and made wood type for a very long time in Wisconsin. There is an abundance of it in Wisconsin. And there are still printers in Wisconsin because of W Madison, University of Wisconsin Madison.

Is that something you would like to do in the future? Produce your own font?

I love typography, and I would love to design a typeface someday. I think it would be long time from now because I recognise how incredibly complicated it is to design a good typeface.

I collect wood type, and I have some beautiful wood types in my collection; I don’t think I can improve on it. I’ll just keep collecting type and making little doodles in my sketchbook. I don’t know if I’ll ever actually design a typeface because I think that I want to focus on doing new things with old tools and making drawings that people engage with before I want to open that can of worms,

You make an effort to go on an artist residency each American summer. Has there been a particular residency that has given you a breakthrough, something that helped you develop your style and think, yes, this is me?

Weirdly enough, the residency that really helped me a breakthrough was not one that was, I mean, it was definitely in a sort of rural area, but it wasn’t, like in the woods. And it wasn’t in an artist studio. It was this place called Dorland Mountain Artist Colony in Southern California. The reason it really propelled my work forward is I got to the studio and it was a writer’s studio. The walls were white, the floors were white. Everything was white. And freshly painted.

I had been working completely with charcoal up until then. But charcoal is so messy. I sat there for, like, 30 minutes thinking what am I going to do? I got into my truck and drove into town and bought a bottle of ink. That’s when I started drawing with ink. I had a month of nothing to do but learn how to use ink. It was really beneficial to me.

That’s a long-winded way of saying, getting out of your studio and your comfort zone and making artwork someplace else with different restraints and different advantages is going to make your artwork better or at least different. It’s going to do something.

Do you find being surrounded by other creatives as a faculty member teaching letterpress and graphic design fuels your own work?

Being in higher education gives me freedom with what I’m creating. I really hated freelancing. I did it for three years and I did fine. But it was a lot of work; it was super stressful and wasn’t fulfilling. I wasn’t making good work. I was just making work, and now I get to make good work. Well, I hope, I hope it’s good.

Going into academics and having the flexibility that I’m not reliant on the money coming in from my art has allowed me to make better art and experiment more. And my students are amazing, I’m lucky they like me and want to discuss art a lot. The time balance can be hard so I mainly create during my residencies. But there are other benefits: we had a visiting artist this week who’s making incredible stuff, and I got to sit and chat with them for 2 hours. That doesn’t happen when you’re isolated and making work by yourself. We had an opening for them and I got to meet a bunch of friends who are also artists and talk about art.

It doesn’t have anything to do with my work at all, but any conversation about art can help move your own work forward. I need to live in that space.

Are there any artists that you particularly admire or that have influenced your career up to this point?

There are a ton. Visually, I love Christina Mrozik, Zoe Keller, and Beth Cavener. There are so many artists but mentors like David Wolski, Paul Brown, and Karen Heft, people with who I have had really in-depth conversations about art-making and why I’m making artwork inspire me. My friend, Tanya Argenson. I have access to all these incredible and intelligent colleagues that, although our work is completely different, I think influence what I make and how I speak about my work. I think the people who really influenced me are the people in my immediate vicinity. And my mentors, I’m super lucky. People are just so generous.

How important do you think that art in general, not just your art, grows our awareness of environmental issues?

I think it’s really important because you can’t reach everybody through one medium. I mean, we talked about it earlier that I really struggle with the written word. And if that was the only way to access this information, it would be super detrimental.

Some people will come across a piece of art and think it’s really neat but that will be the end of their interaction. And that’s fine. But every once in a while, people will lean in a little bit and want to read about it or email me or get involved. If I, or other artists, can pique someone’s interest in that way it’s worthwhile. There are a lot of artists that are doing a really incredible job at just that. It’s hugely beneficial, we should all do our part.

This is the part that I can play. It has to be beneficial because it’s the thing I can do.

What’s on the horizon for you? Is there a project are you working on that you would like to share?

I have my first international solo show coming up. It is the perfect place to take a bit of a risk with new things. I think this is the best work I’ve made. I’m excited because I know my work will be building off of this, playing with letterforms, and illustration.

Finally, what does art mean for you? Is it a form of therapy, a compulsion, a career?

This sounds like a very graphic design professor answer, but it’s a communication tool. I don’t mean that in the, you know the sterile way that could sound but in that it was the only communication tool available to me at one point.

Now it is the communication tool that I am most adept at. You couldn’t exist in higher education and not be able to read and write, and I’m capable of doing those things now. But there was a time where that was impossible. Art was how I communicated. So I think it’s about communication. It’s about using a tool that I’m comfortable with to tell people how I feel about things, to share how I feel about things. It is the thing that made me into who I am because it was the thing that gave me the confidence to push beyond what was expected of me.