You have probably come across Jen Kiaba’s darkly surreal images, each one a page in her visual diary titled Burdens of a White Dress. You may even be aware of their truest meaning. Helping Jen to process her experiences of the cult she grew up in, each image is incredibly personal. But getting to a point where Jen Kiaba could share her experiences was a long and terrifying journey. The cult had a firm grip on her mind, having manipulated her very thought processes for over twenty years. Once she had managed to break away, fear and shame engulfed her in new ways – but she had to find a way to freedom, once and for all. To regain control and no longer live in silence.

However, anxiety can be all-encompassing. How do you overcome the fear and vulnerability to take those steps forward? Below, Jen Kiaba shares her story on how she found a way through the fear to create something unique – and use art to help heal herself and others.

Jen Kiaba: Overcoming Fear

Soft autumn light danced across the wooden floorboards of my living room as I bussed an empty tea mug into my kitchen. I crossed the path of a sunbeam filtering in through a window, and a small black cat curled up by my feet mewled her protest from the floor.

“Sorry sweetie,” I said, about to step aside and forfeit my spot in the warm afternoon sun until a buzzing in my back pocket distracted me. I pulled out my phone to examine the screen. The cat heaved herself up and swished between my ankles, as though pressing me to move on. But I was rooted to the spot, frowning at the message from Mom:

Father ascended.

Though the words were in English, my brain couldn’t process them for a moment. They required me to traverse a path into a world I had escaped over half a decade before. I held my breath and squeezed my eyes shut, trying to will myself to stay in the present, where the words had no meaning or bearing on my life. But it was too late.

Free at last

Mom wasn’t speaking about my dad. Nor did she mean that anyone had boarded a plane, or spontaneously acquired the gift of flight. She was referring to Rev. Sun Myung Moon, the man that she believed was the messiah, and had taught me to call “True Father” as soon as I could speak. When she said he’d ascended, she meant that he had died.

The room tilted slightly as my head felt simultaneously light, and too heavy to stay perched on my shoulders. I sunk to the floor, joining my cat in the comfort of her sunbeam, while I tried to process. Seemingly delighted to have a companion, the cat purred and rubbed against my hand, knocking the phone out of my loose grip. As it toppled to the floor, I heard another notification. From the phone’s landing place a foot away, I saw the message from my sister:

And then I cried.

A past never forgotten

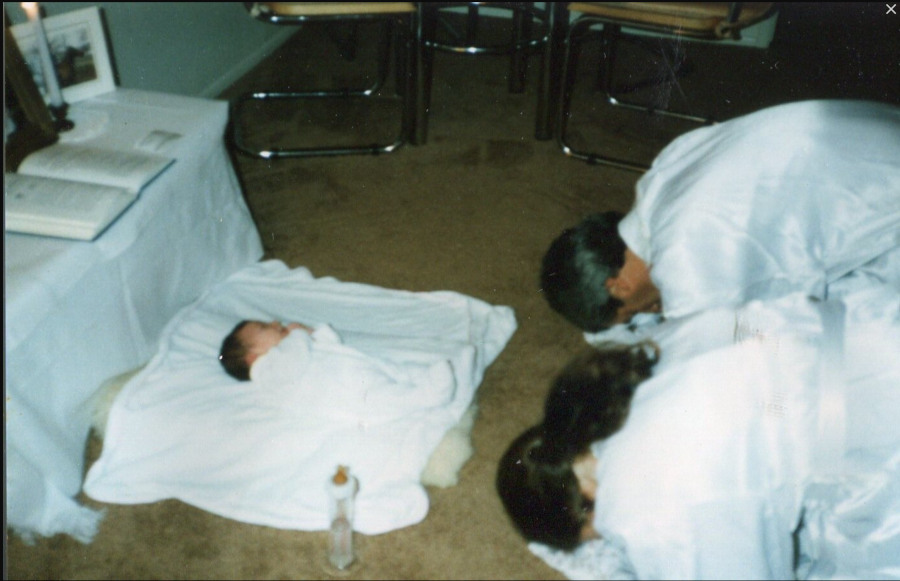

I was born and raised in the Unification Church, a religious group that the media considers to be a primary example of a cult. Most people remember them as the Moonies; they were one of the most feared new religious movements of the 1970s and 1980s, and Rev. Moon a kind of boogie man.

Though I had rarely met the man growing up, Rev. Moon was a force in my life. He had chosen my parents for one another, and they were married in one of the mass weddings that the Church had become famous for. As a child, I’d always assumed he would choose my husband for me as well someday. But as the years went by, I found myself questioning his doctrine and his supposed messianic mission. Whenever I found myself in that place of doubt, my parents and members of my community told me that I was being invaded by Satan, that I needed to cut off my negative thoughts to get back into alignment with God and True Father.

By the time I had turned twenty, in 2004, my parents and the Church community had ground me down enough to force me into an arranged marriage with a stranger, a man of Rev. Moon’s choosing. As I stood in the back of the ballroom of Moon’s East Garden mansion compound, saying wedding vows to a stranger in a language I didn’t understand, I knew that I needed to find a way to escape both the Church and the marriage. It took two years of fighting, but eventually I did.

Freedom: It’s not so simple

When I initially left the Church, I’d been too ashamed to tell many people my story.

No one would understand, I told myself. They would think I was weak, stupid, or both. Now, I realized that I’d had another unacknowledged fear: that, somehow, Rev. Moon could still hurt me even after my escape.

And that sunny September afternoon in 2012, as I sat weeping on my floor, I felt like I could finally stop running. The man who had controlled so much of mine and my family’s lives for decades could no longer hurt me. While I wasn’t going to argue with anyone about whether he had ascended or descended, I knew that my sister was right. We were finally free.

How to break the silence?

After I picked myself up and dried my tears, a need welled up within me. I couldn’t remain in silence anymore.

First, I tried penning essays that detailed my experiences growing up in the Unification Church, and the reasons why I left. But I didn’t have the language to describe the trauma, or the education to even truly understand what had happened to me. I didn’t understand what coercive control or thought reform looked like and had simply normalized them into my upbringing.

So I turned to images to describe how I felt.

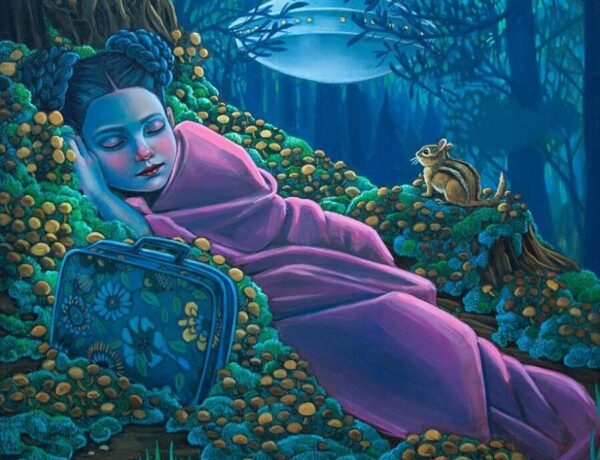

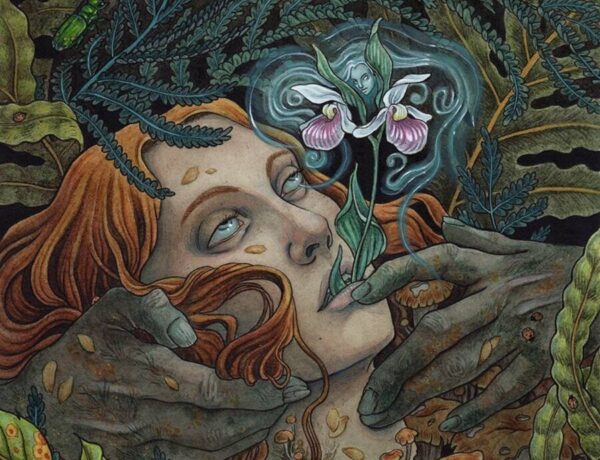

I had been working in photography for about five years at that point, sometimes using models and other times turning the camera on myself. Deep down, I knew I’d been circling around something essential, too afraid to dive in and really explore the crux of what I was trying to say. Then one day in the summer of 2013 I took a model out to the Hudson River, gave her a white dress to wear, and photographed her weighted down with driftwood.

“The burdens of a white dress,” I murmured to myself, clicking the shutter. A shiver of recognition went through me, and I knew that this was the essence of what I wanted to say and needed to explore.

How Dare I?

I sat with the audacity of the thought for a few more months, quaking every time I even considered speaking directly about my experience through art. How dare I?, I thought. Then it hit me. That was my old conditioning; I was still silencing myself long after the Church was there to do it for me. But I wondered: if by remaining silent, was I also being complicit?

So one afternoon shortly after, I entered my studio with a sketch, a white dress and a coil of red and white rope. I wanted to demonstrate the mental and emotional bondage that I had felt leading up to the events of my forced arranged marriage. But I shook as I set up my camera. I was so blinded with fear as I posed and used the remote to activate the shutter, that when I arrived home to process my images, I realized they were all out of focus.

Maybe that’s better, a part of me said in relief. After all, speaking out could still be dangerous. Not only could people judge me, but there might be a chance that the Church could come after me.

But at home the sketch kept seeming to stare at me from my desk. Something inside me was screaming to be heard. I couldn’t just let those out-of-focus images be my final attempt at speaking my truth.

A few days later, I returned to my studio. Trying to keep my breathing calm, I set up the camera and pulled on my white dress. I could feel the buzzing of fear at my temples, trying to blur my vision again. “You’re OK, it’ll be OK.” I repeated the mantra, trying to will the fear back as I checked my focus and took my shots.

A momentous step: facing the fear

That day the first image in my Burdens of a White Dress project was born. It’s a series that now comprises over 60 images exploring the feminine experience of growing up in a high-demand group, as well as the intersections of purity culture, coercive control, and the sexual, mental and emotional traumas that occur as a result. Most of the images are self-portraits, and they use red, black and white as both a color scheme and the primary symbolism with which I explore these issues.

Over the seven years that I’ve worked on this project, every time I show up in my studio to create a new image, fear was there to greet and try to stop me.

In the beginning, I saw that fear as a monster with fearsome teeth, ready to devour me. I kept waiting for the consequences that it promised me: shame and judgement from others, retribution from the community that I had grown up in. And it’s not that those things never came. Occasionally they did.

But eventually I understood that my fear was trying to keep me safe. I wanted things that felt fundamentally dangerous, and my fear was trying to keep me small in order to protect me. Once I realized that fear was simply doing its job, I began to greet it and offer it respect. Sometimes I even thanked it for being so vigilant. But I always let it know that I could take things from here.

Thus acknowledged, my fear began to settle down, its voice more easily relegated to the background so that I could do my work.

New level, same devil

A year after I began my project, I partnered with Unchained at Last. They are an advocacy group dedicated to ending forced and child marriage in the United States. I began mentoring other women who had escaped forced arranged marriages in the Unification Church.

When the director asked me to create an image for the group’s annual fundraiser, I wanted to return to the waters of the Hudson River and create an image that spoke of healing. Problematically, I didn’t know how to bring my sketch to life and make it a self portrait as well. I’d need to be in the water, much too far for my remote to activate the shutter. But self portraits felt safe. Bringing in a model, explaining my vision and purpose felt vulnerable. And with that feeling of vulnerability, my fear roared to life again, louder than ever.

“Ah, there you are, old friend,” I said, smiling and shaking simultaneously. “Thank you for trying to protect me.”

My gratitude was feeble, laced with frustration. And unlike before, my fear wasn’t backing down.

But I knew that I wanted this. Pursuing a new level of visibility and advocacy in my art felt like an important new dimension of my creative mission. Why would my fear try to protect me from something that I wanted?

Eventually I realized that what I was striving for was a deeper connection in my work. But that connection required a new level of the same vulnerability I’d been so afraid of in the beginning. Once again, my fear was trying to keep me safe, and would go so far as to prevent me from accessing and accomplishing the things that I wanted if necessary. Instead, I forged ahead in finding a model, scouting a location, and bringing my vision to life.

Everything you’ve ever wanted is sitting on the other side of fear

Since then, I’ve developed a new kind of gratitude for my fear. Although we are often at cross purposes with each other, not only have I realized that it tries to keep me safe, but I have learned that many times it acts as a compass for the things that I want.

The George Addair quote, “Everything you’ve ever wanted is sitting on the other side of fear,” can be found plastered across mugs, stickers and wall art.

But the essence of it never truly struck me until I understood that when my fear was the loudest.

It usually meant that I wanted the very thing that it was trying to protect me from: more visibility, more connection, more depth in my work. Eventually I learned to lean into my fear, to listen for when it was the loudest. When I found that place, it usually marked the direction I needed to move towards.

The road is ongoing

A few months before COVID shut the world down, I found myself in a gallery near San Antonio, Texas, preparing to give an artist talk. It was the opening reception for my solo show, and my palms were clammy, my breath coming in ragged pulls. When the gallery owner called me to speak at the front of the salon, I squeezed my eyes shut to fight the dizziness that was threatening to overwhelm me.

I opened my eyes again and looked out at the small crowd gathered around my work.

All I could hear was my fear: “What if these people judge you? What if they laugh at you?”

Thank you, I thought, I’ll take it from here. Then I shared the story of my art.

Perhaps people judged me that evening. I wouldn’t know. None of them jeered or made rude remarks. Instead, after my talk, people gathered around to share their stories and discuss the issues addressed in my art.

At one point I felt my fiance, the man I’d chosen, wind his arms around me from behind, resting his chin on my head. I smiled, leaned back into his strong embrace, and felt a deep gratitude for the connections I had found and the life I had built on the other side of my fear.

Conference on Religious Trauma: Healing Through Art

On May 15, 2021, Jen Kiaba will be speaking about healing through art at a virtual conference. The Conference on Religious Trauma (CORT) has two ticket tiers, but you can use Jen’s special discount code MAIL15 for a $15 discount:

- For USD$150 you will be able to attend all sessions, and also gain access to all session recordings for up to one year.

- For USD$75, you may not attend the live sessions, but you will have access to all recordings for up to one year.

Student discounts are available ($35), and CORT will also make considerations for those under financial hardship during these challenging times. Potential attendees are directed at registration to send CORT an email regarding these two matters.