It isn’t the precision of the artwork of Australian painter Jeremy Geddes that takes your breath away. Neither, paradoxically, is it the suspension of reality that occurs with key elements in each of his pieces; the spaceman suspended against a deserted downtown backdrop or crouched, oversized, within a gritty alley; buildings disintegrating under some hitherto unknown quirk of physics; bodies floating, or segmented, or coalesced into massed limbs.

What truly astounds is that, when seeing Jeremy Geddes’ art, you are not astonished by these things. With no flaw in the execution, nothing to tell the eye that what you are seeing is not as it truly is, then we are left wrestling with the unreal becoming real, and that takes your breath away.

Interview with Jeremy Geddes conducted in conjunction with his editorial in Issue 14 of Beautiful Bizarre Magazine.

Jeremy Geddes (photo credit: Bronek Kozka)

Jeremy Geddes (photo credit: Bronek Kozka)

Australia seems to have produced an incredible array of hyper-realist artists over the years, painters and sculptors, each with their own unique take on the genre – Ron Mueck, Sam Jinks and Patricia Piccinini to name a few of the sculptors, and yourself, Robin Eley, Joel Rea and many, many other painters. Is it something in the water? Coincidence? A national honouring of Jeffrey Smart? What do you think?

I grew up looking at Jeffrey Smart as well as a few other Australian painters such as Rick Amor and James Gleeson. Australian art has been in an interesting position over the last one hundred years, it’s come very much from a European artistic tradition and has looked to Europe and America for inspiration, but at the same time has been very isolated. I think this has produced some distinctly Australian traits in art making, some for the better and some for the worse.

There has been a certain bleakness in much Australian art, it can be seen in music, film and the visual arts, and often is very distinctive. It’s hard to pin down exactly where it emerges from, undoubtedly Australia’s unforgiving landscape is a factor. But there has also been a dearth of technical proficiency. Much of the techniques developed in painting during the 18th and 19th century were lost in the modernist push in the early 20th century, and whilst pockets of art communities continued these traditions around the world, the Australian population was small enough that they essentially became lost to generations of painters growing up in the mid to late 20th century. As a result, many painters in Australia reinvented the wheel with technique, myself included. Again, this is no doubt positive and negative, with styles that were distinctive, but also possibly not as proficient.

The internet has ended Australia’s cultural isolation now; we are now bombarded with a tidal wave of overseas influences. It has become incredibly easy to find demonstrations of classic painting techniques online, something that was unavailable to me as I was growing up. Hopefully we can use this new technology to enrich ourselves where it is appropriate, whilst still retaining our distinctive and unique voice.

Fortress, 2013-14 [Oil on Board , 54 x 90.5cm]

Fortress, 2013-14 [Oil on Board , 54 x 90.5cm]

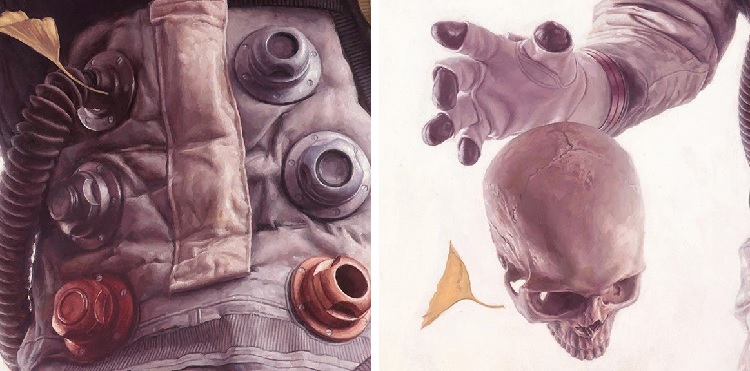

Begin Again 2012 [Oil on Board, 21.5 x 25″] and detail

Begin Again 2012 [Oil on Board, 21.5 x 25″] and detail

Your representation of the astronaut in urban landscapes poses the question – are the landscapes alien or is the astronaut? The disparity in scale in some of the works also invokes Swift’s Lilliput, the loneliness of isolation among others. Who does the astronaut represent for you?

I love the comparison to Swift, and I love disparities in scale, but these are questions I can’t and don’t answer. I’m interested in creating paintings that lack conceptual frameworks to help explain or contextualise the image. Everything I have to say about my paintings I try to say within the painting itself. I don’t create my work with an allegorical or symbolic language, I just try to work instinctively and intuitively.

The meaning of the landscapes and the figures are limited by exactly what I’ve painted, nothing else. When I’m working on them I can see various interpretations I find engaging or convincing, but these are my own stories, no more or less valid than others, and so I have no wish to share them and possibly colour other people’s perception.

Bringing it back to basics, what inspires you to create ~ and what motivates you to keep creating? Did you have artistic influences in your youth, or are you driven by other inspirations; music, literature, daytime television…?

Painting is what I do, I don’t really see it as needing external inspiration. However, whilst I’m developing a work I often use certain music pieces as a sort emotional thru line, it can help me see clearer what elements to incorporate or leave out. Podcasts and audiobooks have also been a boon, just to help me through some of the more mundane and grinding parts of the painting process.

A Perfect Vacuum, 2011 [Oil on Board, 20 x 35″]

A Perfect Vacuum, 2011 [Oil on Board, 20 x 35″]

We have many creatives in our audience and they just love the gory details of technique. Can you share your process with us, how you decide on your media (mostly oil on linen, isn’t it?) and how this has evolved over your career.

It’s essentially all oil on board these days. I’ve been using oil paints since I was young, and it’s the medium I intuitively understand now, so I’m not sure whether I ever consciously adopted it. Rather I fell into it and kept running with it. It has the most versatility of any paint medium, and so I couldn’t really think of any reason why I would abandon it now.

It terms of technique, I begin with an initial drawing up in ink, and then proceed to a thin wash over the board to outline the broad colours and tonal values. After that I proceed with the major detail pass, using fairly thick paint with little or no medium. This phase is easily the most time consuming, often taking many months. Once this has been finished, I go over most parts of the painting with thin transparent passes and glazes, modulating colours and adding additional subtlety to the surfaces. It’s a process that in its particulars is, I think, wholly my own, as it has evolved through much agonising trial and error. That said, I’m still cognisant of the many flaws it has, and at the moment I’m in the process of pulling it all apart and searching for whether there’s a more rational way to put it back together.

“I think reality at its core is a messy random unstructured storm of particles, and any order we impose is merely a figment of our imagination.”

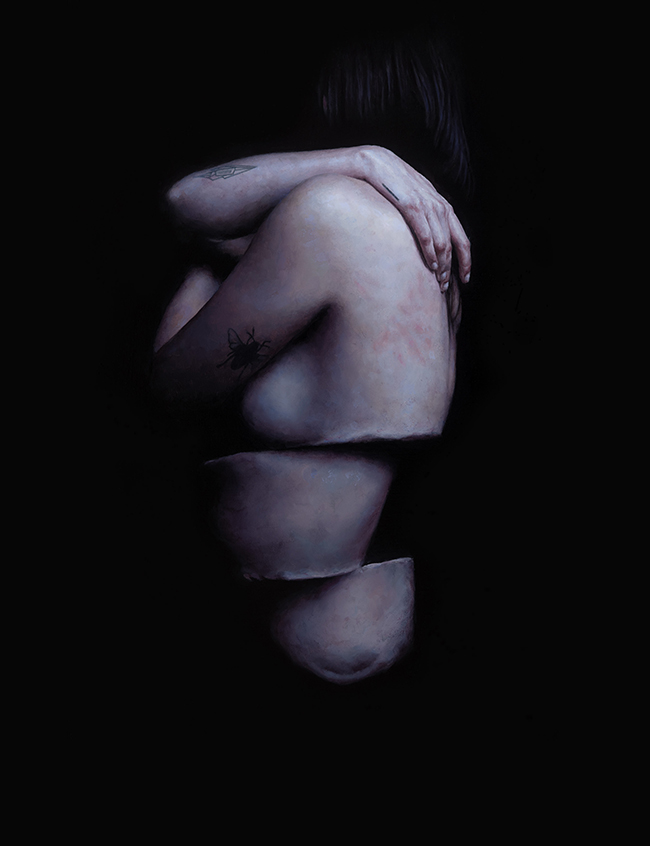

Hypostasis, 2014 [Oil on Board, 37 x 37″]

Hypostasis, 2014 [Oil on Board, 37 x 37″]

Foundation, 2015 [Oil on Board] and detail

Foundation, 2015 [Oil on Board] and detail

Ascent, 2014 [Oil on Board, 29.5 x 29.5″]

Ascent, 2014 [Oil on Board, 29.5 x 29.5″]

White Cosmonaut, 2009 [Oil on Board, 27 x 26″]

White Cosmonaut, 2009 [Oil on Board, 27 x 26″]

Your works can be described as though provoking, technically brilliant, challenging … but perhaps never as uplifting, joyous. Have you ever considered a journey on the lighter side, or would you prefer to leave that to others? …and if so, who’s work brings that other side out for you when you see it?

I see many of my works as having an uplifting quality personally. Perhaps it’s people’s initial frame of reference that colours their ultimate interpretations. My outlook on life might be classified as rather bleak I guess. I’m a materialist and nihilist who rejects any meaningful conception of free will and who sees peoples’ internal life as a muddy and incoherent conglomeration of evolved mental processes that fools itself into thinking it has a degree of independent action. I think meaningful communication is in many ways almost impossible, even amongst those other humans you might share the most commonalities with. I think reality at its core is a messy random unstructured storm of particles, and any order we impose is merely a figment of our imagination. Given that starting point, there is beauty and serenity in the smallest acts of kindness or interaction. It is all we can hope for, and that makes it all the more profound.

“Undoubtedly philosophers are in the right, when they tell us that nothing is great or little otherwise than by comparison.” ― Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels

Jeremy Geddes and his beloved dog, Colin the whippet

Jeremy Geddes and his beloved dog, Colin the whippet