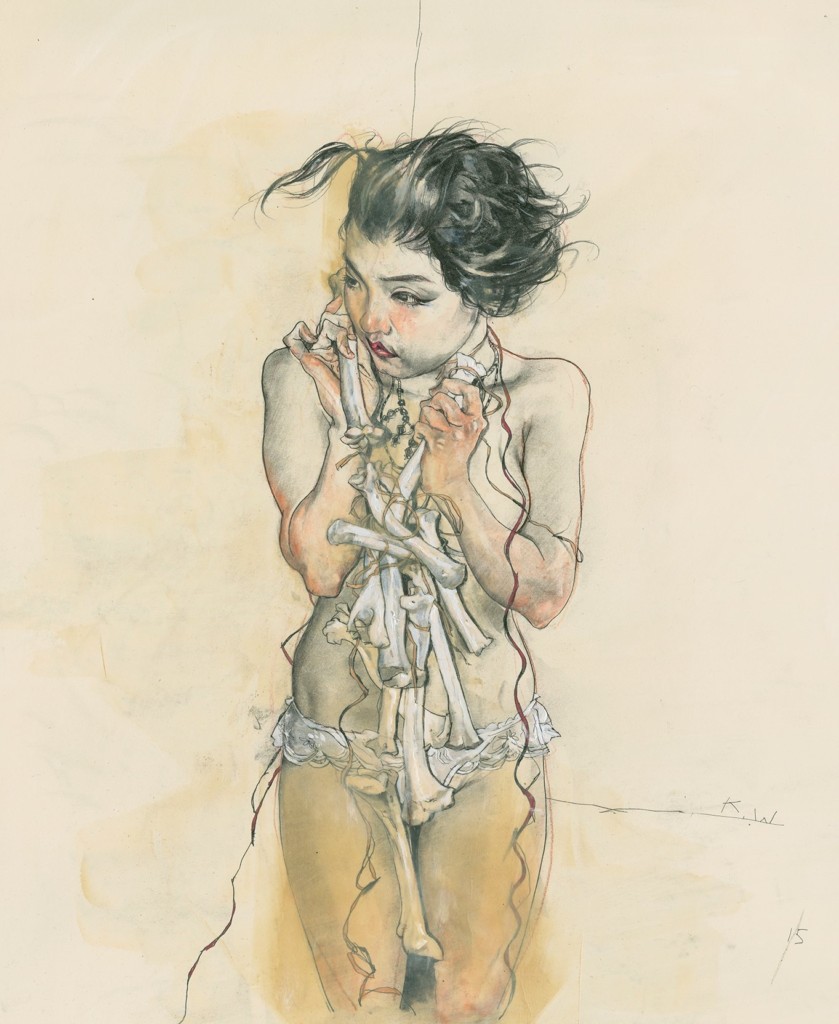

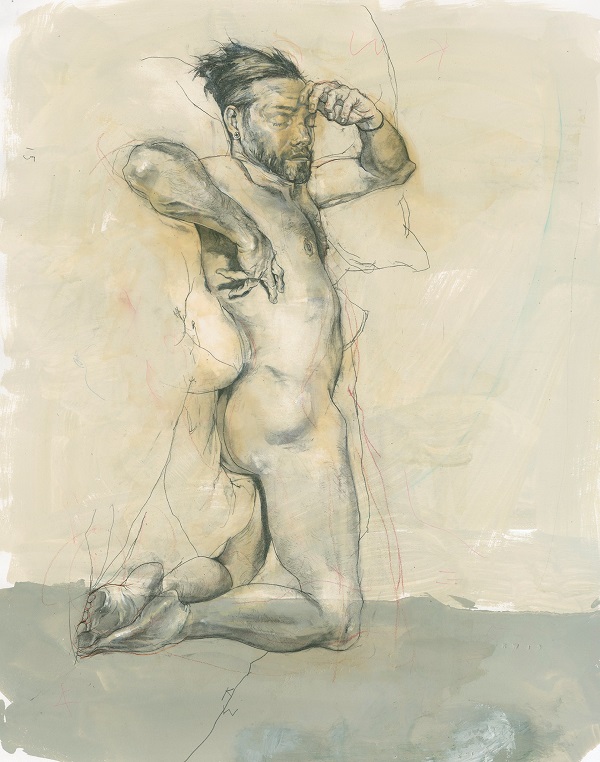

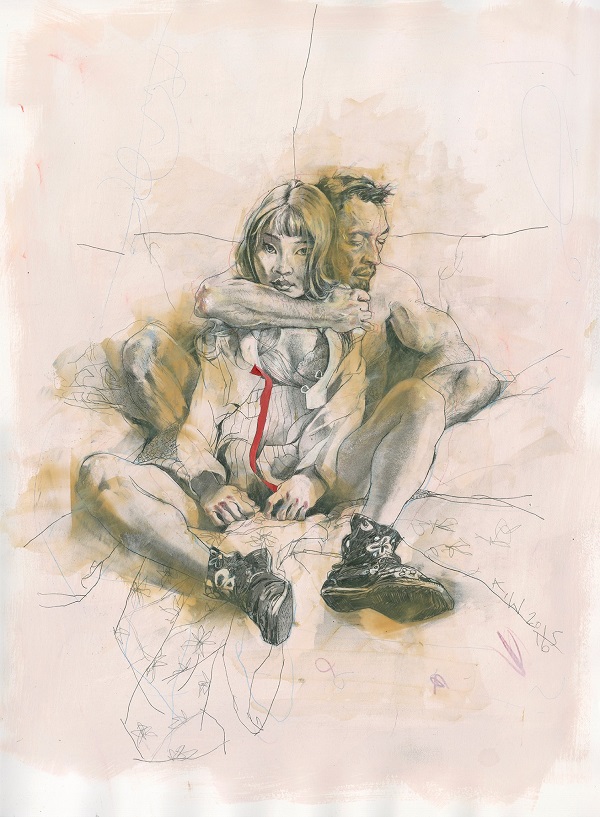

The art of American painter Kent Williams is not easy. Don’t expect his work to hold you by the hand while it gives you a simple narrative to take away, satisfied that you have fully grasped its meaning. Kent’s paintings take hold of the human condition, deconstruct it one raw moment at a time, and present it to you in all of its flawed glory.

Beautiful Bizarre was fortunate to have a conversation with Kent for Issue 013, to take our readers into the studio with him and shed some light on his background, his inspirations, and his creative process.

Interview conducted in conjunction with Kent Williams editorial in Issue 013 of Beautiful Bizarre. We hope you enjoy!

Kent Williams

Web | Facebook | Tumblr | Instagram | Twitter

How much of an influence was art to you in your early years? Did you find support and inspiration in becoming a creative from within your family?

I’ve been drawing or picture-making since I can remember. My earliest images consisted of monsters and creatures that were very much influenced by the Universal and Hammer horror films. No artistic influence from my family except possibly my father’s desire to do things right and well, and his ability to most often achieve this. I wouldn’t say there was an over-abundance of encouragement (my parents certainly had the fear of the standard perception of the “starving artist” model), but there wasn’t discouragement either. They supported me for sure ~ probably based on them seeing me follow through to completion with other interests that I had in my youth.

Who were your early inspirations in art?

It was in college, when I moved to New York, that the whole of the art world opened up to me. I don’t recall having ever visited a proper gallery or art museum as a kid. Whatever exposure I had, I got from art books and magazines, I suppose. My move to New York – in the middle of the art world – was the first time I was exposed to all that New York had to offer, and I soaked it all up like a sponge. I fell in love with it all: going to the Met and MOMA and seeing all those originals for the first time. I discovered Egon Schiele and Degas, Franz Kline and de Kooning; I saw Rembrandts and Francis Bacons for the first time! That raw, unencumbered energy of Bacon was fuel for the fire! – and along those lines, it wasn’t very different than what I got from Frank Frazetta, whom I had a passion for when I was in high school. I started developing a taste for artists who I didn’t even know about just a year earlier. Was having discussions about Eric Fischl and Julian Schnabel in school, and I had an immediate attachment to the paintings by Leon Golub.

What do you think is the main difference stylistically and thematically between your graphic novel / comic work and your fine art practice. Do you find there is much cross-over in your process or do you maintain a conscious separation between the two?

I don’t see, and I think most people would agree, that there is a difference stylistically between my graphic novel work and my “fine art practice.” I draw and paint the way I draw and paint. I’m not assuming a “style” regardless of the medium I’m working in. My language or voice is my voice. Thematically, or content-wise, naturally there’s a difference. With the graphic novel, I’m storytelling. With the other, I’m usually responding with an emotive and analytic reaction to a given thing. Highly personal. Both can be this, I suppose, but they’re very different vehicles.

If you’re seeing a difference, it’s probably simply that I haven’t done any graphic novel work in over a decade, and naturally – hopefully, my work itself has developed, grown during this stretch of time.

I’m going to quote myself here: Style (a term I generally shy away from when used in the context of art) should not be something one consciously chooses and places upon oneself. Style, or one’s artistic language, is something that comes about as a by-product of sweat equity during the sincere pursuit of something better than he or she is capable of doing. I hear so often from other artists, especially students, about wanting to “find a style.” But in so many cases these folks are not willing to put in what it takes for this to happen: to put in and to discover the passion for observation, for drawing, for looking outside of their insular worlds – to feed and nourish the passion that will ultimately lead, by the act of doing, to a personal language. They think they can kind of just step in and choose a “style.” The pursuit should never be to find a style, but rather to look, to discover, to soak in, and then to transcribe as best he or she can. And through this most simple and complex WORK, one’s look, or language, or style will develop on its own.

The blurring of abstraction with realism to a greater or lesser degree is a signature of your work ~ what process do you to decide the boundaries, and do you do it from a particular direction i.e. here realism ends and abstraction begins or vice-versa?

By incorporating both of these extremes in my paintings I am able to weave the tangible with the intangible. This incorporation of disparate calligraphy generates a sort of electricity, a juxtaposition of opposing forces that makes come alive the human aspects of my picture-making and/or meaning. Also, quite frankly, including both – or creating a world where both can exist – allows me the opportunity to bring into play my enthusiasm for, and influences from, historical and contemporary art. Real estate where the blessed and forsaken can play together.

Portions of fabrics, often with traditional Japanese patterns or themes, are a frequent element of your work – is there a particular relevance of this for you?

I’ve always seemed to be more interested in peoples and cultures other than those that immediately surround me. As a kid, I was particularly interested in Native Americans, which I suppose I could partly attribute to my family’s part Cherokee lineage. Honestly, though, I think a lot of my cultural interests were initially stimulated by going to the movies so much as a kid and watching films like ‘A Man Called Horse,’ for example. I remember so vividly witnessing the bear claws buried in Richard Harris’ chest as he spun ritualistically in the middle of the tribal lodge with the sun bearing down on him from the roof opening, and all of the members of the tribe looking on. A ceremony in which he was becoming a member of the tribe, I believe? This and other films, at a time when Native Americans started to no longer solely be portrayed as the enemy, shaped my connection with other worlds. I was always more than happy to play the “indian” when we played cowboy and indians with my friends. I wanted the bow and arrows, when they wanted the guns.

And then Bruce Lee came along for me at around age 10 or 11. I really do contribute a lot of my love and ability for drawing the human form to discovering Bruce Lee. I must have drawn thousands of pictures of him, copied from magazine after magazine. Anything Bruce Lee that I could get my hands on, I would grab up. That obsession led to my interest in the martial arts, in particular Okinawan Karate, which then led to my interest in the films of Akira Kurosawa, and so on and so on.

Of course, Japanese art had a large influence, especially compositionally speaking, on the Impressionists and other artists of that era — artists that had a large impact on my work, such as Degas, Whistler, Bonnard.

I’m just taking all this further, in different combinations, and with a contemporary mindset.

Kent Williams is represented by KP Projects in Los Angeles, CA and EVOKE Contemporary in Santa Fe, NM