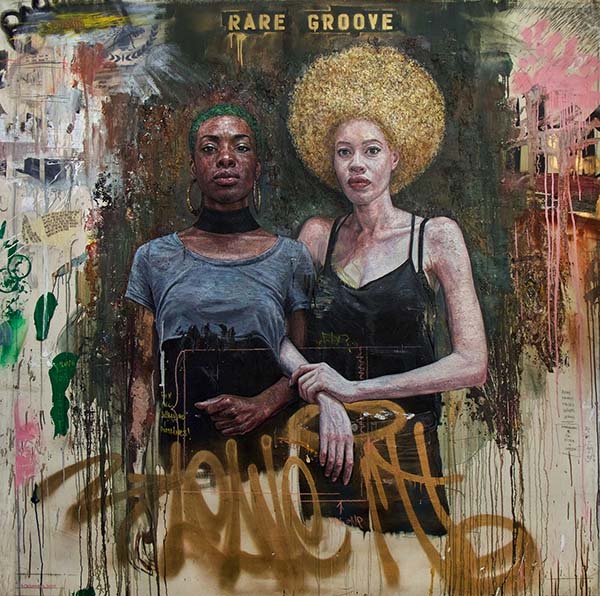

In case you have been transported from a different universe, let me tell you something about Beautiful Bizarre Magazine ~ we love the figure! Figurative art is at the heart of our aesthetic, and we are always overjoyed to see and promote this art oeuvre at every possible opportunity. We are very excited to be able to tell you, then, about the latest exhibition organised by the wonderful people at Poets & Artists and co-curated by Didi Menendez and Walt Morton. To be held at the Wausau Museum of Contemporary Art, in Wausau, Wisconsin, this exhibition features many friends of Beautiful Bizarre, including issue 019 cover artist Tim Okamura, and others whose work we have long admired and are thrilled to see featured!

Many thanks to co-curator Walt Morton for this insightful essay on the power of the figure in art.

Painting the Figure Now

Co-curated by Didi Menendez from Poets & Artists and Walt Morton

Wausau Museum Of Contemporary Art

Wausau, Wisconsin USA

July 7 – September 28, 2018

Why paint the human figure now?

People have been illustrating the human figure for at least 30,000 years. There are worldwide paintings on rock walls that indicate a primordial desire to express the human form. Five thousand years ago, Egyptian artists painted complex figures on the walls of tombs. Around the year 900 CE, human figures were carefully rendered in illuminated bibles. Innovation in figurative painting ignited in the late 1400’s with Leonardo DaVinci who invented convincing ways to express dimensional drawing effects and to paint light and shadow. DaVinci gave rise to the next five hundred years in painting history, where artists advanced the craft of figure painting and portrait painting to an all-time high. This was a progression that took centuries of accumulated knowledge and invention, usually passed hand-to-hand, ceremoniously after years of hard labor, from master to student. You had to grind your own paint. Nobody had a digital camera. And there was no internet.

Fast forward to 2018, artists continue painting the human figure. Why haven’t we exhausted the subject after all this time?

For one, figurative art investigates our identity: who we are and what we are. What does it mean to be a human being? In the past, figurative art was often nationalistic, celebrating cultural heroes loved by a mass of admirers. An example is Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze (1851, The Metropolitan Museum of Art). But the internet has fractured traditional barriers of region and identity and created a million tiny social networks and countless digital tribes. More than at any time previously in history, humans have the power to choose who they’ll talk to. Chat happens anywhere on planet Earth with wifi. Distance is no longer is a limiting factor. You can pick your digital tribe, and membership may be spread from Moscow to Buenos Aires.

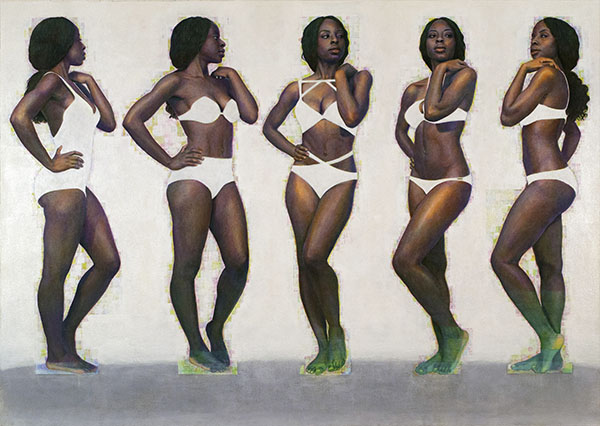

Who are your people now? It’s your circle of friends, chatting and messaging on a multitude of digital devices. Your followers on Instagram care deeply about you. Everybody is a “brand” today, and skilled self-marketers speak to their followers with emotional images that shape thought itself. The images you see in someone’s Instagram stream define your idea of that artist and their identity. Yet it’s very unlikely you’ve met them in the flesh. The structure of communication across these smart phones, tablets, and laptops is deep, not superficial. It affects viewers’ thinking, a concept popularly known as the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis. When artists paint a figure, they are actively encoding ideas about identity into the work. The art might be about female identity, gay identity, Latino identity, or any micro-subcultural group. The fact that it’s a painting underscores the hands-on designed encoding of ideas. A painting is not a found object like a photograph. Every bit of a painting (be it blobs of paint, marks, or color choices) is a result of human direct intention to code specific things. The whole point of the exercise allows a viewer to decode the art and extract some message. If the message is agreeable and well-executed, the viewer may get out a Citibank VISA card and buy the art. Buying art is a cash vote for solidarity around ideas of identity and representation.

No matter how fringe, the internet has an identity-matching group for you. If you want to chat about Marvel’s new gay black Spider-Man, there is a community interested in probing this identity and welcoming any new visuals to support the discussion. If you draw or paint gay black Spider-Man, people will be hotly interested in how you present this figure. Your painting tells us what you think it means to look gay. And to look black. And to look like Spider-Man. In this new configuration, a painting of gay black Spider-Man becomes an icon, a thing charged with extra meaning beyond what is literally seen, and the icon speaks to an in-group of followers on a privileged channel.

One of the reasons superhero movies are popular now is we’re all interested in the idea of flexible identity and especially the key super-power of shifting your identity, a shift always signaled by a costume change in what the figure wears. A mask, a cape, the visual change overlies something deeper down, normally hidden. There is an implicit thrill in the idea of having a secret identity, an urge that runs counter to an equally strong impulse to be open about yourself. Back in 1969, if you were a Star Trek fan, you were likely in the closet about that fandom, since it felt terribly geeky to identify yourself as a “Trekkie.” But since that time, over the last fifty years, the geeks built the internet, earned trillions of nerd dollars, and now run the entire economy on Amazon. Today, it doesn’t matter how obscure your identity obsession is, go to Comicon and you’ll meet the rest of your Sailor Moon tribe celebrating living on the fringe with great joy.

In 2018, traditional aspects of fixed identity are in greater flux than ever before. In the past, religions, nationalism, and racism tried to draw hard definitions, segregating groups and limiting freedoms. While these issues are evolving and unresolved, today’s world encourages different thinking about identity. Gender-neutral bathrooms, LGBTQI rights, gender fluidity, and changing standards and terminology are familiar news. For artists painting the figure, the issue of labeling is significant, since labeling connects to how work is sold, a practical reality of marketing oneself.

Artists, more than most professions, have always been conscious of the personal identity they present to the public. There are a lot of mythic representations of the eccentric artist in popular culture, and these work to establish the special nature of the art product, different from products of the butcher, plumber, or janitor. The artist identity is always a manufactured product, often a collaboration between the artist and a pioneering gallery selling the new. The public face of Andy Warhol was just as conscious a creative work as any of his paintings or prints. Warhol knew the audience didn’t just want art, they wanted a show — a distraction, amazement, a jolt. Marketing the artist can be show business.

The marketing notion leads us to a core issue attached to painting the contemporary figure, which is “truth.” The word “true” is a hot potato in art, since it can be loaded with heavy meaning (“a true artist”), but more practically one hears things like “true color” as part of any debate on accuracy. Words like “honest” and “authentic” are favored by savvy art sellers these days. Any whiff of sincerity carries a special power in a global factory economy that takes your money in return for handfuls of disposable tech-gizmos.

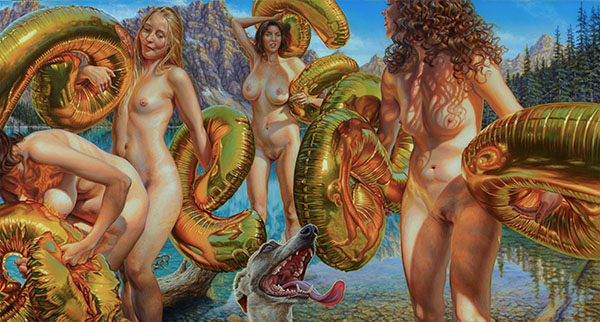

In other words, mass-market consumerism has transcended morality for almost every product we buy. However, contemporary paintings represent a retro antidote. A return to an era of handmade items. Part of the magic in painting the figure now is carried in this increasingly rare connection to the world of handmade craft products. Painting requires real artists to work with actual physical materials and to produce a singular object in the material world. The one-of-a-kind nature of painting supports the curious idea of the real thing. An object that is truly itself and nothing else.

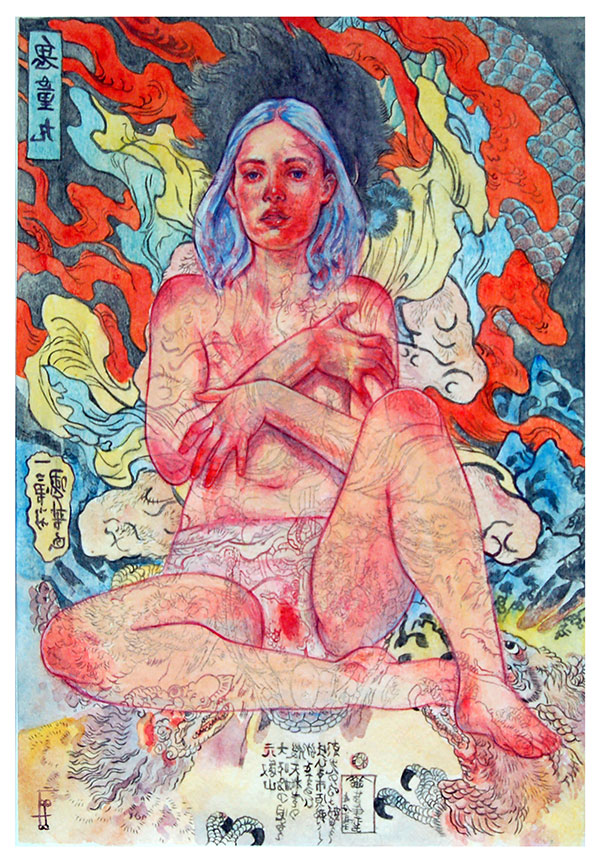

Truth is where great liberties get taken by artists painting the figure. While a finished painting on canvas, linen, or aluminum is a real physical object, the image is never entirely true to the source material. The physical reality of the painting is an indisputable thing, but we’ll never know for sure what the model actually looked like. No, despite a modern obsession with more megapixels and high-definition detail, even the most hyper-realist contemporary painting presents a view of the world skewed by the artist’s mind.

Skewed is a good thing. We want the artist’s outlook and mental state to impact the look of the painting, because without that interior psychological aspect, we may as well just use a camera for an objective, non-partisan view. The camera is quicker, easier, and has greater density of information. But what the artist gives us in a figure painting is a human-calibrated selection of most-essentials. What’s left out — that says everything about what the artist believes is most important. In considering the works shown in 2018’s collection for Painting The Figure Now, this should be your first question: “What does the painting tell me about how this artist thinks?”

Human life is fragile and relatively short. To capture an image of the human figure that endures centuries touches on a power to hold back the ravages of time in a way normally forbidden to biology. A painting offers us the capacity for the important moment, frozen forever. The artist who thinks to capture the figure this way sometimes dares the flaming pit of ego, with a selfie. In following Rembrandt’s example of forty self-portraits, from youth to withered age, we find hope to discover the truth about oneself. There is hubris in this, a wish for understanding, recognition, love, even egomaniacal greatness. More than that, a marker that you do exist. You matter, right here and now and forever.

Even if you are a queen, a president, a hero, or a great beauty, the one thing that will erode your image and erase your identity is time. You cannot last. But a painting of you, if nothing else, may remind future generations of your marvelous, spectacular existence. This is also a good thing: to capture us as we are, bold humans clawing a daft mark across endless eternity.