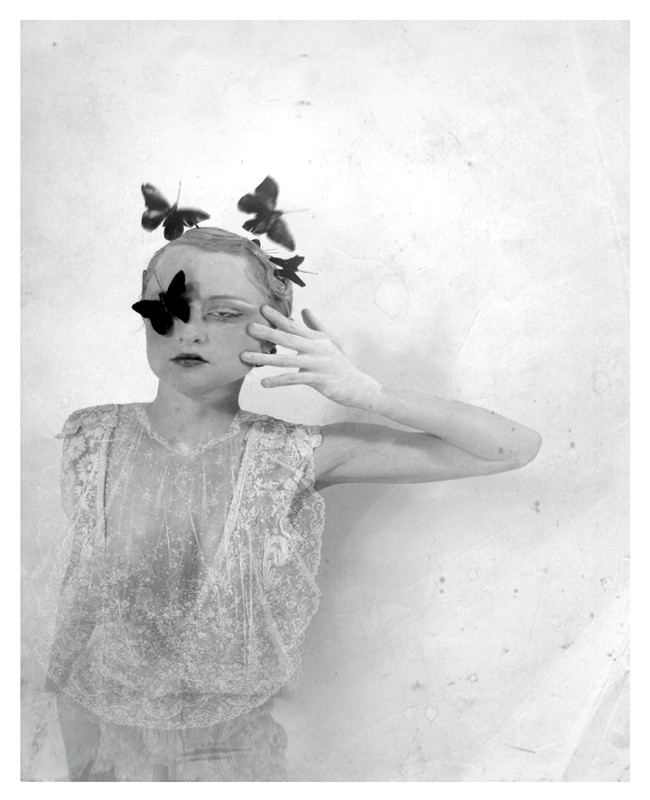

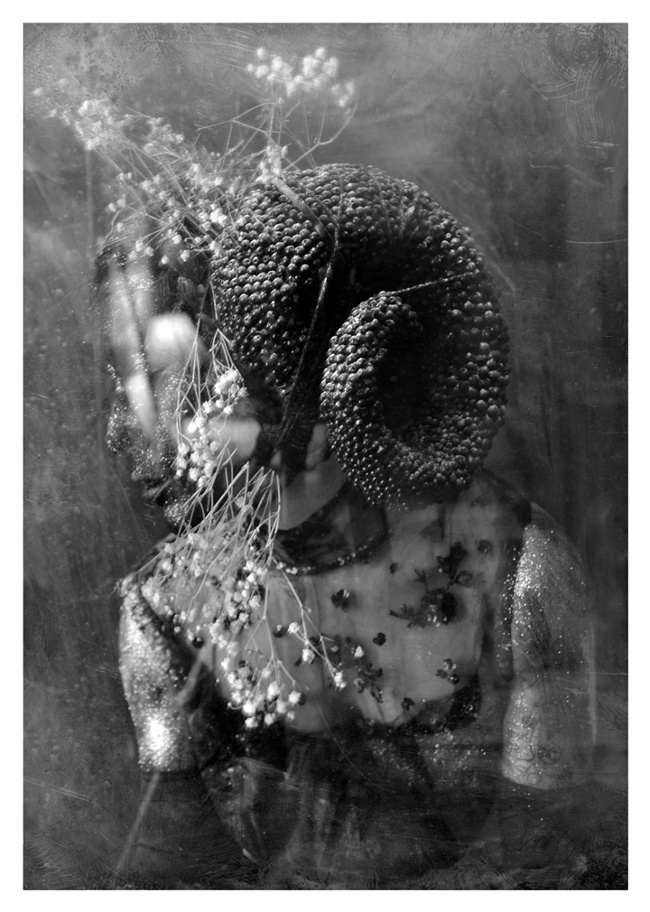

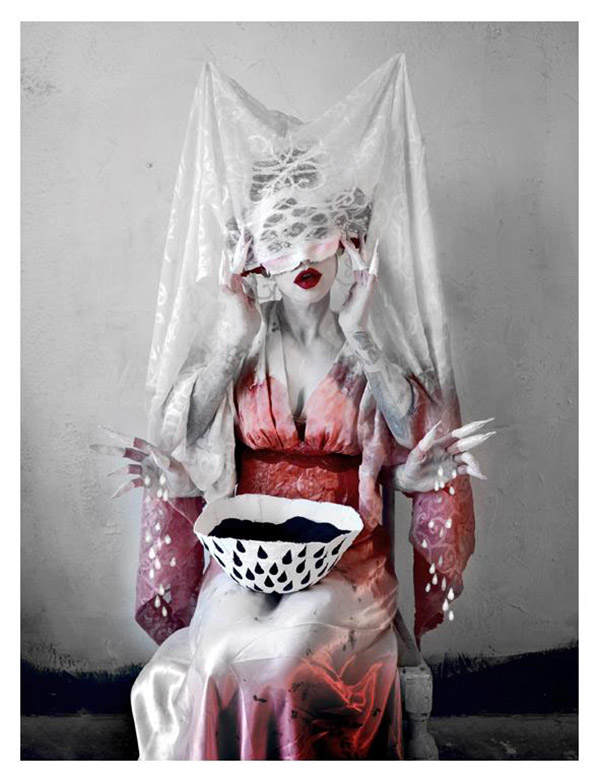

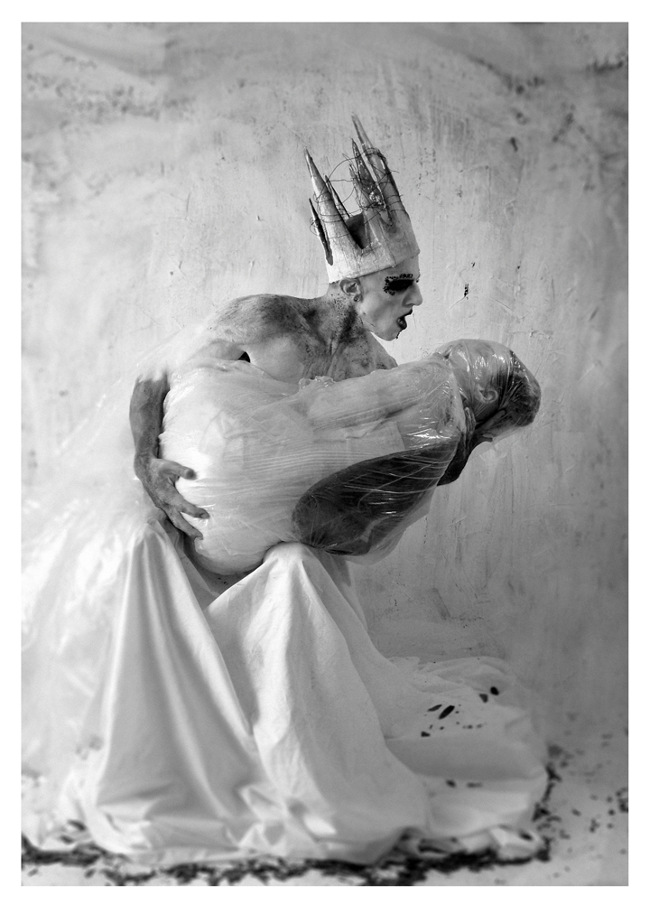

Hauntingly bewitching, Darla Teagarden’s self-styled photographic creations share her innermost thoughts with a refreshingly veracious grace. Like spying through the Looking Glass, perhaps it takes a moment to absorb the scene in front of you before clarity unveils itself; questions become answers, answers bring more questions. Candor wrapped in symbols, her works may often display riddled experiences. Speaking to her, however, is a whole new experience in itself. Grounded and perceptive, Darla opened up about her past, her influences and driving forces in our interview for Issue 016 of beautiful.bizarre. Enjoy!

There are echoes of turn of the century fashion in your photography – Victorian lace attire, and the large eyes and well-defined lips if the iconic 1920’s spring to mind. Your time working as a stylist and later as a historical cabaret dancer have, presumably, influenced these characteristics, but what first drew you to this vogue time period?

The Goth Culture in San Francisco in the late 80’s early nineties had a strong vintage aesthetic. It was a mash up of Victorian, 1920’s 30’s and punk. Vintage stores were still overflowing with gorgeous mourning gowns, cloaks and velvet. Intellectualism played a part so studied history and in a way embodied the Gay 90’s, Wiemar era etc.. Lots of decadence, lots of LOOK.

Do you think your time in cabaret has had a specific effect on your artwork now as a photographer?

Definitely. Cabaret is about low brow expression, gut expression. It’s a kind of Fever Dream in a way. There’s always going to be something staged, seedy, pointed, about cabaret. A kind of Tableau vivant. That’s how I see my work. Your use of predominant poses reminds me of the old black and white films where without the element of sound, actors often over-dramatized their acting to evoke stronger emotional responses from the audience. This intensity is very alluring.

How did you get into photography?

I did a lot of “alt modeling’ in the 90’s so it was there, but it wasn’t until I wanted something interesting to be done with my 2 year old son and myself (ten years ago) did I consider doing more. I didn’t want to pay someone else to re-create my concepts so there was only one thing to do.

This seems like a rather personal outlet for you. As a mother as well as an artist, do you try to keep the different parts of your life separate? Has your family ever become involved in your creations?

It can be difficult when I need time to do things like, make a dress out of paper towels for example. This type of concept photography is very time consuming, but in essence I’m just a mom who works at home and anyone who does that knows it’s hard to determine when you are available and when you aren’t. My son was in a lot of my earlier photography when he was little, but now he’s not comfortable behind the camera and that’s perfectly OK with me.

Do you feel your works are there as more than a single image? Are they part of a larger series of events?

My work is always a representation of real life, but not real life much like the cinema you described. This allows it to be broad but also intimate because almost everything I do is about shared condition. Especially the feminine condition. It’s an outer response to inner life. Inner life is something children are rich in and something we tend to lose quite a bit of as we age. My work keeps me connected.

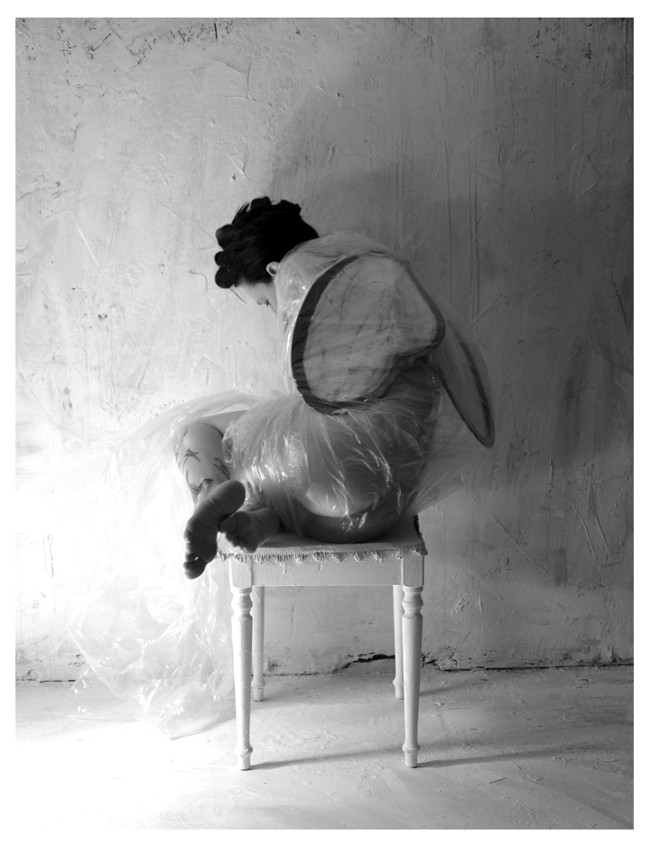

I believe that you make all the theatrical vignettes yourself before setting up and (primarily) posing for your images. Where did this idea come from? Has the process changed much over time?

It’s about practicality. It’s difficult for me to work around model’s schedules since there is a lot of staging. I shoot in my bedroom and I find it easier to just use my own body. I realize that I may be better known If it shot more people outside my own environment, but it feels natural right now. I’ll probably change this as time goes on. It can be physically demanding.

It must take time to put some of your more complicated vignettes together! Do you ever get lost in the process?

Lost, yes, but not in they way you may have meant… It’s not ‘fun’ per se. It’s challenging to keep coming up with ways to say a big thing with very little. It’s a cathartic ‘lost’ but not a ‘fun’ lost most of the time.

The constraints of limited room to make your visions a reality must cause you to really think outside the box; would you say this creative adaptation has pushed you to be a stronger visionary?

It pushes me yes. I like to compare it to a poem. The poet never uses extra words, every word matters and has a connection to the theme and meaning. Visually, it’s very similar. I have to keep searching for key visual words and it’s not always easy. Other times, it easily presents itself.

Have you considered bringing your visions outside of your bedroom – outdoors, perhaps, where you can utilize larger props and different spacial limitations (or lack of)?

I do when I can. I worked with artist Carrin Welch who does the enormous Rocking Horses Of The Apocalypse, for example. But even that was around the corner from my house!

Even though many of your images are faceless, you are the main model throughout your photographic career so far. Why are the majority of your photographs self-portraits?

Again, it’s practical but also I know what I want to do. The nature of my work is very much like a silent film and I feel I don’t need a perfect face or body to achieve that. In an offhand way, I find it cathartic and perhaps even feminist as a 44 year old woman and mother to put on a claw hand and pose behind a fur wheel, then sharing it with thousands. It’s somewhat absurd. Allowing myself to be any character I choose without a need for perfection or social agenda is freeing.

Would you consider using more models, or even joint-collaborations in your future designs?

Yes, I’m beginning to feel a bit lonely lately! I would like to get more people’s perspective on my concepts. It’s inevitable that my work changes when I put a new person into my space. That too I think is very interesting. I always learn something while directing. The model becomes almost like another independent limb and he/she will do their own interpretation to some degree even when I’m being specific.

Can you explain your technical process when taking a photograph?

In the simplest terms, it’s much like a mini play. I start with a concept, sketch it, then run around town looking for ways to build it economically. Then I do technical rehearsal, then dress rehearsal looking at what I’d like to change or add. After all that is done I pick a day to shoot. By then my camera is set up and my timer is ready. I shoot until I can’t do anymore and that’s it. I take what I get and I almost never re-shoot.

How long does it take to finalize an image after the photo has been taken?

Because I’m in full costume and make up, I let the shoot stay in the camera for at least a day before I go through it. I guess I have a ritual now. Scrub off the grease paint and get busy with something else. I usually go get food and a cocktail with friends or family. Then in the following days I can look at it with some objectivity. As far as editing goes, there’s not a huge amount so specifically, maybe about three hours after going through the shoot I have picked my shots and have edited it. So, one to two weeks of work to build a moment.

On your website you describe your work as a way to “serve abstractly […] as means for communication, protection, ritual and a sense of place.” Can you share with us a deeper insight into these specific points of focus?

It’s very important to me, no matter how abstract, comical, sad, pretty, childlike, broad or specific my work becomes, that in the end it’s a poem to shared human experience. And on a personal level, my art literally saves me and protects me from these experiences by allowing me to recall and rearrange my feelings to fit a more tolerable mind set. The act of dressing up and taking pictures helps reduce the enormity of something to a different animal. One that I can communicate with without crying or getting depressed. But that’s what art is, a kind of alchemy. Magic and practicality in one.

Are there any particular aspirations that have taken hold as you continue to progress on your journey as an artist?

From the beginning I’ve had this ongoing fantasy: Simply put, I’m on old woman with a life dedicated to art with solid work to show for it. Work for my son and potential grandchildren and friends to seek and find. Work that allows them to see and find a part of me whenever they want to for as long as it matters. Everything else is dessert.

Do you still practice any other forms of art?

I write, but only for myself.

Keeping your whimsical essence (flying witches and swarming flies around singing heads, for instance) there are also some very raw moments in your portfolio – would you describe your work as sometimes macabre?

Fairytales always have a macabre lining. I see some of my work as cautionary parables because life is full of them. Sometimes the lesson is short and sweet and sometimes you live with a royal fuck up for the rest of your life. That’s where the macabre aspect comes from for me. Living with choices.

Though you create a lot of works to say or share something in particular, do you find people understand, or have you experienced your audience asking for you to share the meanings behind the pieces?

What’s odd, is that it seems to have changed some recently. Instagram has ”INSTA” in the word for a reason. I find if I go into detail about my purpose for the photo it doesn’t seem to garner interest for the meaning the way it used to. People either immediately identify or they see the surface and move on. Broad themes like witches or animals get the most feedback and the heavily symbolic stuff seems to interest a select audience. People almost never ask any more, but when they do I oblige. It’s not important to me to explain pieces any more. They either enjoy the symbolism or they enjoy the theme.

Have you found that a concept has ever grown beyond what you thought it would be?

Concepts often start out as one thing and end up another. Sometimes bigger, sometimes smaller. I think this is pretty typical for any medium.

The way that you display your photography for exhibitions blows me away; take Hidden Woman for example that recently showed at Last Rites Gallery: it had its own little curtains to hide the artwork if you want to! Do you think of aspects like this when taking the photographs, or is this art on top of art a brand new creation inspired at a later date?

The concept frame for “Hidden Woman” was something I wanted to do for a long time. I adore mixed media and I love miniatures. It seemed like a simple way to work those interests into the story telling, into the theatre of my photo concepts.

Is there a particular photograph or series that you feel especially connected to?

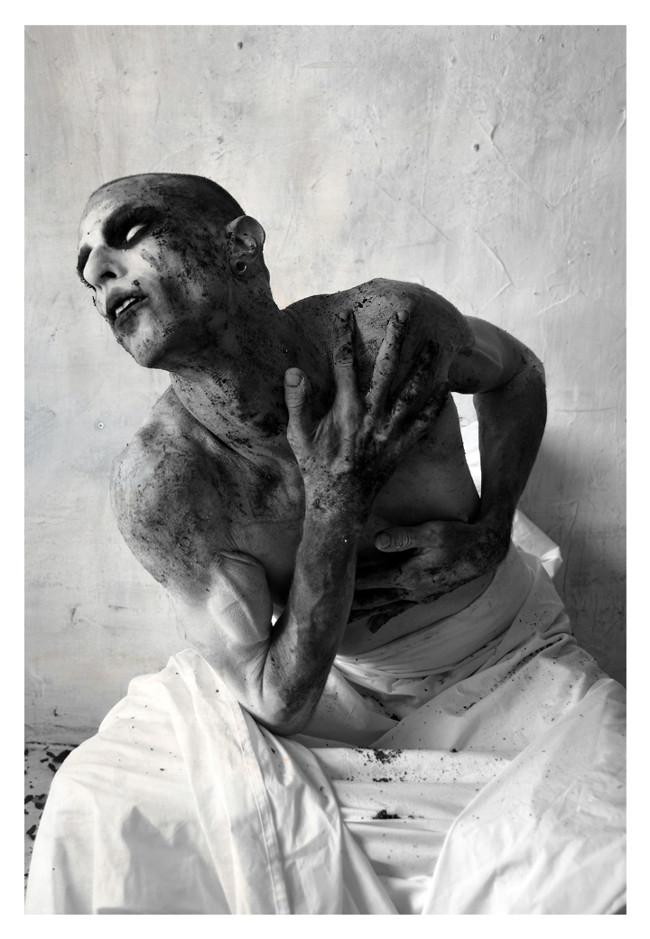

At this point ALTARS series says the most, but there’s something special to me about my series of images with Mr. Goff in Lamentation for Mrs. Fly. It’s about two friends who’ve had a ocean of life experience between them coming back together to share it. We survived and at times we even lived. There’s something always profound about being in a friendship with someone who knew you when you were a little dangerous.

The ALTARS series is a selection of self-portraits exploring living with mental illness. What did you learn in creating this series?

I learned how silent most people are forced to be about their illness. ALTARS seemed to allow strangers to come to me and talk about the ways it affects their jobs, their relationships etc. For me it was an honor to be trusted with their stories and to know it was a positive thing and not just a series of ‘creepy photos” or that it helped more than only myself.

How do you think your experiences in the art world have made your life better?

Community. I’m pretty guarded and tend to keep to myself but my work has allowed me to meet so many different types of people and allowed me to know I can relate and let people in. I don’t have to work as hard to be understood as maybe I once had.

Sometimes it’s impossible not to influence others and be influenced by the people you meet, especially in the art community. Have you had any experiences with others in the art community that particularly struck you? Perhaps a moment that opened your eyes or started a new path?

There has been few artists who personally had something to do with my growing interest in photography and in art. Late Ex-Rolling Stone photographer turned fetish photographer Charles Gatewood had a big impact on me. He was very forthcoming with his technical processes and with how he conducted his business. Two artists (then a couple) Enrique Vargas and Nick Bohn were two more… They documented our unusual group of friends in brilliant ways. Nick ended up moving to New York to make films and has since passed but he encouraged me to try new things. Nothing intimidated him. Also late Jazz Photographer Herman Leonard encouraged me with his genius and friendship. He invited me into his world and instilled the notion that human story and your relationship to it, had to come first.

It’s obvious that a lot of yourself goes into each photograph; plenty of people are interested in what you create… Are your works for sale anywhere at the moment?

Nothing is for sale right now.

What about future shows or events, anything coming up in the pipeline?

Yes! I’m honored to be doing a group show at Jeremy Hush’s space called The Convent, in Philly. It’s called WINTER FLOCK – it opens in February 2017. After that I may do another more in-depth show there as well. It will be nice to meet everyone finally. So many people I’ve known only online.

I look forward to knowing what everyone’s laugh sounds like.