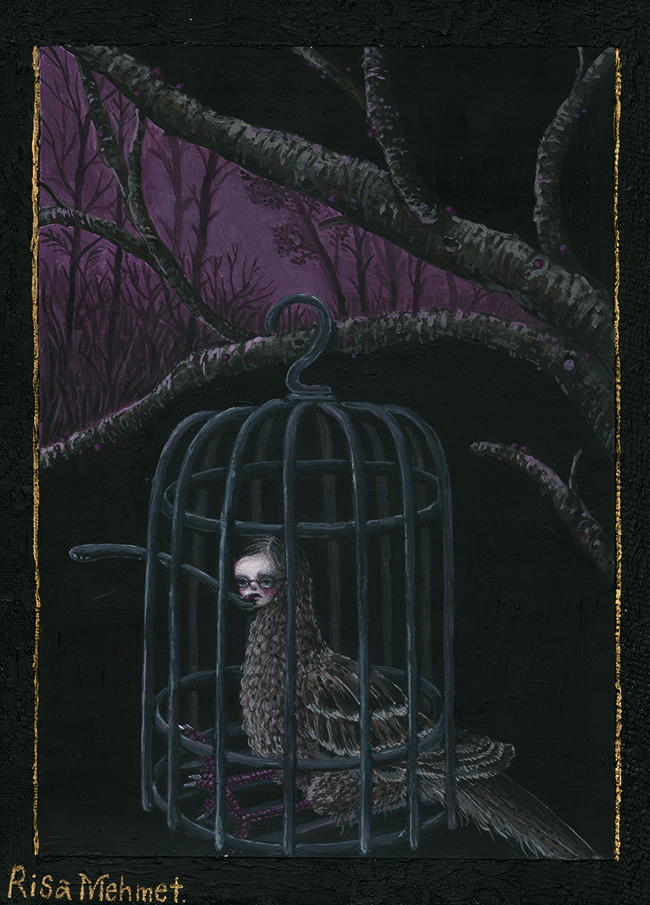

Risa Mehmet’s paintings look like illustrations from one never-ending fairy tale…a disturbing fairy tale that predates the Brothers Grimm by several centuries and incites too much mass hysteria to remain in our cultural memory. Or perhaps one in which black stallions with porcelain doll faces drown for an eternity in black tar as featureless maids look on, in which blindness and body horror and mutilation are customary. Set in a kingdom far, far away, everything is dreamy and pastel.

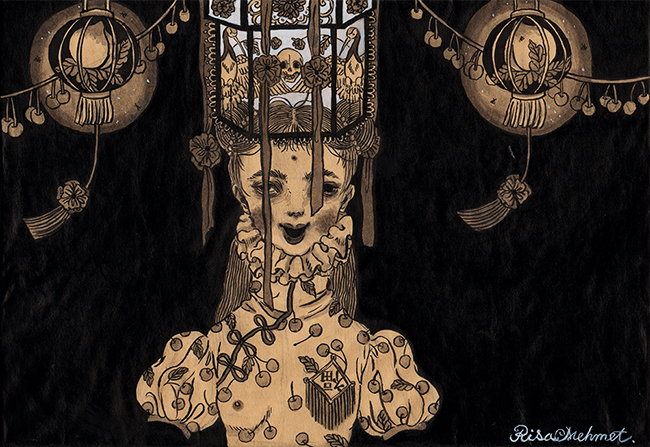

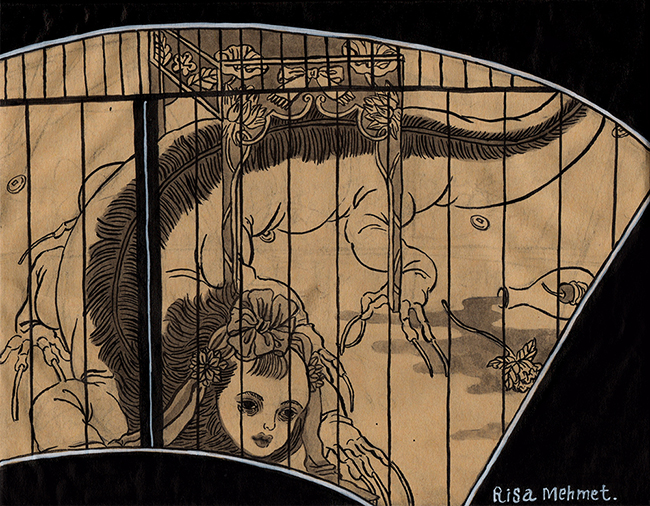

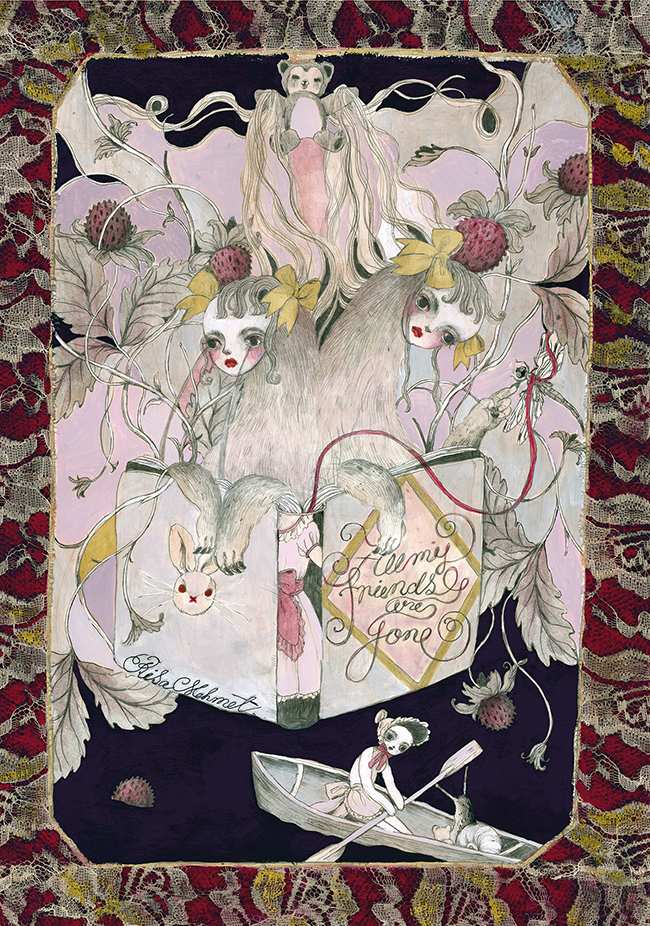

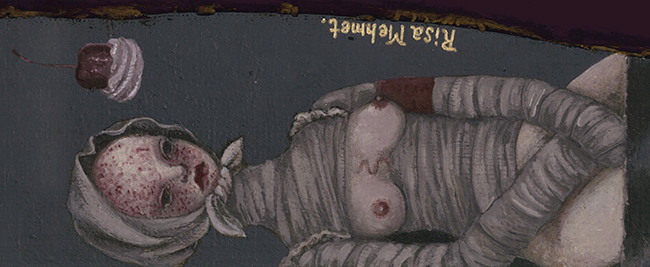

The Japanese artist’s paintings are studies in duality. The most oft-hashtagged is “creepy cute,” which is somewhat insultingly reductive given the intricacy of her work. “Daintily macabre” or “morbidly lovely” might be more fitting, but still a critical hysterectomy. It’s tempting to use such shorthand because this paradox is so characteristic of Mehmet’s oeuvre. Spotlighting the sweetness of her faces would obscure how they are frequently attached to the bodies of deer or horses or creatures less comfortingly defined, twisted into excruciating positions and given proportions that would scandalize Cronenberg. Fixating on the frills, lace, and stuffed toys would ignore how often they are stained with blood.

Mehmet’s relative lack of fame is so baffling, considering the zeitgeist has never been more attuned to the whole “innocence corrupted, but, like, meta”/self-aware-whatever-personality-disordered-Lolita-with-a-heart-of-lead thing since Courtney Love graced America with the “kinderwhore” in the ‘90’s. Mehmet appears to get the most recognition from her modest legion of Internet fans, to whom she sells packages of limited-edition buttons and stickers and postcards. The apotheosis of her career, if we’re talking big names, was at Tokyo’s Hidari Zingaro Gallery, Gallery Maison D’art Tokyo and Gallery Maison D’art Paris. She had a spread called “Creepy Sweet” in Issue 41 of Asian fashion-art magazine Little Thing, which came with a copy of her art book. Her most recent exhibition was part of China Circus, a Chinese-themed show commissioned by Japanese antique shop Amanojaku featuring three of her paintings.

In an attempt to taste the brain matter behind the art, a la Hannibal, I browsed Mehmet’s blog and sent her interview questions over email (due to the language barrier). It’s such an odious cliché, but I came away with more questions than answers, with at most a back alley Freud’s understanding of her art and psyche, and how they intertwine. Her blog’s description reads, “My creations are produced by my sadness, mysterious disease and some traumatic memories. Sometimes I make dolls.” Lots of dead or dying flowers. Rose petals drowned in tea. Crucified butterflies. Candles shaped like severed hands. Pictures of her bedroom, which is literally a garret, slanted skylight and all.

Risa Mehmet, herself, could have been written by a fourth Brontë sister—the one they kept, Oldboy-style, chained in a pastel-colored basement and subsisted on a diet of Earl Grey and edible flowers, with only an abandoned carousel for company. In answer to my asking how she would describe her work, she wrote, “Recording of sorrow. It is the custom for me to put sad memories in the picture that I cannot talk with everyone.” Sad being an egregious understatement. The defining elements of her childhood were trauma and ostracism. The “mysterious disease,” she explained, is a skin condition, which makes her unable to grow hair. This led to abuse and bullying that continued even into her adult years. “So many people asked me on purpose why you are different,” she wrote.

Mehmet explained that her pictures are largely autobiographical. “There was no friend whom I could talk about my trouble with shame, so I draw a picture to pour out my feelings.” She also wrote, “I have been drawing a picture almost every day since I was a little child.” It doesn’t take a genius to do this arithmetic. “A person appearing in most of [my] artwork is myself and slice of my life,” she added. Thus contextualized, many of the recurring motifs in her artwork take on a much darker weight. The prepubescent shape of the faces and bodies. The disembodied blonde wigs. The leaky, rust-colored pockmarks dotting the skin and the bandages that fail to cover it. The ubiquitous wounds, usually over the heart and bleeding profusely. The juxtaposition of one girl-faced animal trapped in a circle of actual girls, or vice versa. “All my friends are gone” in disarming cursive.

But even with the language barrier and intentional mystery, Mehmet’s intelligence and wit—even, dare I say, cheekiness—shines through. She is incredibly cultured for a self-taught artist and lists Dadaism, Surrealism and giallo auteur Dario Argento as some of her influences. Her favorite book (for now) is “Hokuetsu Seppu” by Bokushi Suzuki…a highly complex Edo-period piece of human geography describing life in Japan’s snow country, where she lives. Wikipedia tells me “the text covers 123 themes from multiple angles.” The relentless flow of gorgeously poetic decay on her blog is interrupted by Harry Potter fan-posts, pictures of a chocolate disguised as a silkworm, gifs from Japanese game shows, opulent photos of burgers, pies, and cakes she ate. And when I inquired about her dolls, she wrote back, “I wrote sometimes I make dolls but it is extreme beginner and making for my friends.”

“My favorite story is dark, sad and cruel,” Mehmet wrote. But she immediately added, “I want to tell the story of sad, foolish and sometimes funny like my life. I think the tragedy and the comedy are just two sides of the same coin.”