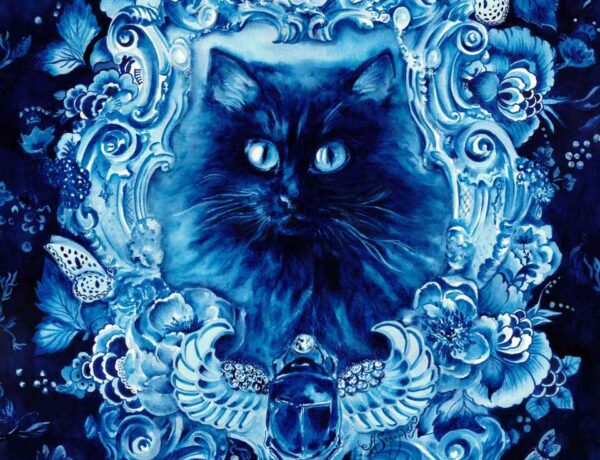

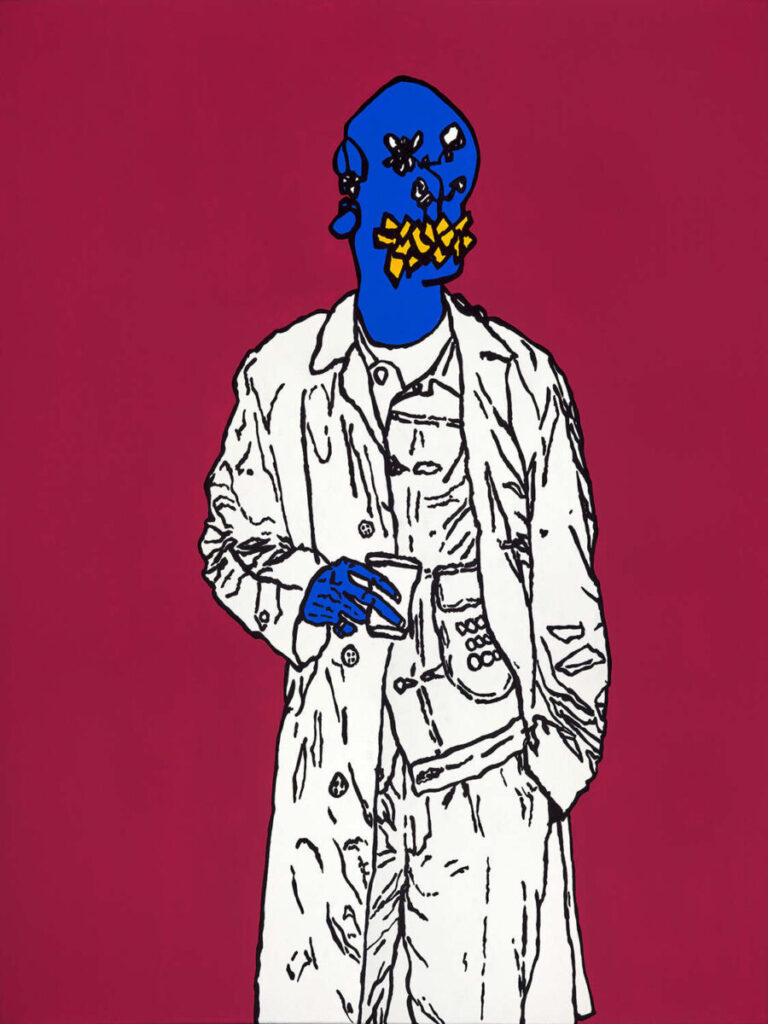

Jean Luc Iradukunda would like to introduce you to his ‘blue people’. As the name suggests, they are blue in appearance, reminiscent of aliens, sporting dark hair and golden teeth. These people are a creation of his own making that are built from a concoction of bold, jagged lines, splashes of flat primary and secondary colours and the most important ingredient, the complexities of the human existence. These ‘blue people’ have a playful tenderness to them as we watch them live their daily lives. Underneath all the bright, playful colours however, lie important, complex themes of identity, marginalization, society and what belonging means as a migrant.

Jean Luc Iradukunda is a painter and software engineer originally hailing from Gisenyi, Rwanda. He currently resides in Cape Town and his body of work explores and draws upon his experiences as a Rwandan migrant living in South African society. Artistically, Jean Luc is best known for his ‘blue people’ which are expressed through his signature use of vibrant colours and abstract, Fauvism flare. He encourages viewers to reflect inwardly working to bridge the gap between cultures as he explores identity, human connection and the everyday aspects of the nuclear family.

Exclusive Interview with Jean Luc Iradukunda, South African based artist, represented by Bender Gallery in Asheville, North Carolina

Bender Gallery Associate, Amanda Kendrick-Deemer, has been emailing back and forth with the painter, Jean Luc Iradukunda, learning more about his process, studio practice and goals for the future.

Hello Jean Luc, I hope all is going well with you. Please give me a summary of your background. I would love to hear about growing up in Rwanda and how you came to be in South Africa. How old were you when you settled in Cape Town?

I was born in Gisenyi and raised in Rwanda’s northern regions, my childhood was enveloped in a vibrant community, rich with cultural traditions and the beauty of natural landscapes. Relocating to South Africa in 2007, at the tender age of nine, I was unaware of the full implications of seeking asylum. This shift in worlds, though bewildering, unknowingly sowed the seeds for my artistic journey, deeply rooting my work in themes of displacement and belonging as my family and I attempted to settle in Cape Town.

The jagged yellow teeth in my pieces act as a device to extend the work’s narrative on human disfigurement. They play on the concept of pareidolia, where even amidst distortion, the essence of humanity persists.

Jean Luc Iradukunda

Can you walk through what a typical day in the studio is like for you? You’re a software engineer as well, how do you balance making artwork and your job?

My day typically involves a full work schedule as a software engineer from 9AM to 5 or 6PM. Post-work, I take a brief nap, shower, have dinner, and then I dedicate my evenings to my art studio, often working past midnight, occasionally stretching to 4AM to meet deadlines. My artistic process is methodical, involving extensive research through reading, films, documentaries, and other online media. I prepare thorough sketches before approaching the canvas, ensuring a clear vision for each painting. This structured approach allows me to efficiently balance my professional and artistic pursuits.

Please tell me about the teeth of your figures and why they are depicted as such.

The jagged yellow teeth in my pieces act as a device to extend the work’s narrative on human disfigurement. They play on the concept of pareidolia, where even amidst distortion, the essence of humanity persists. These teeth, placed where one expects a mouth, push the boundaries of recognition, yet remind us of the human form.

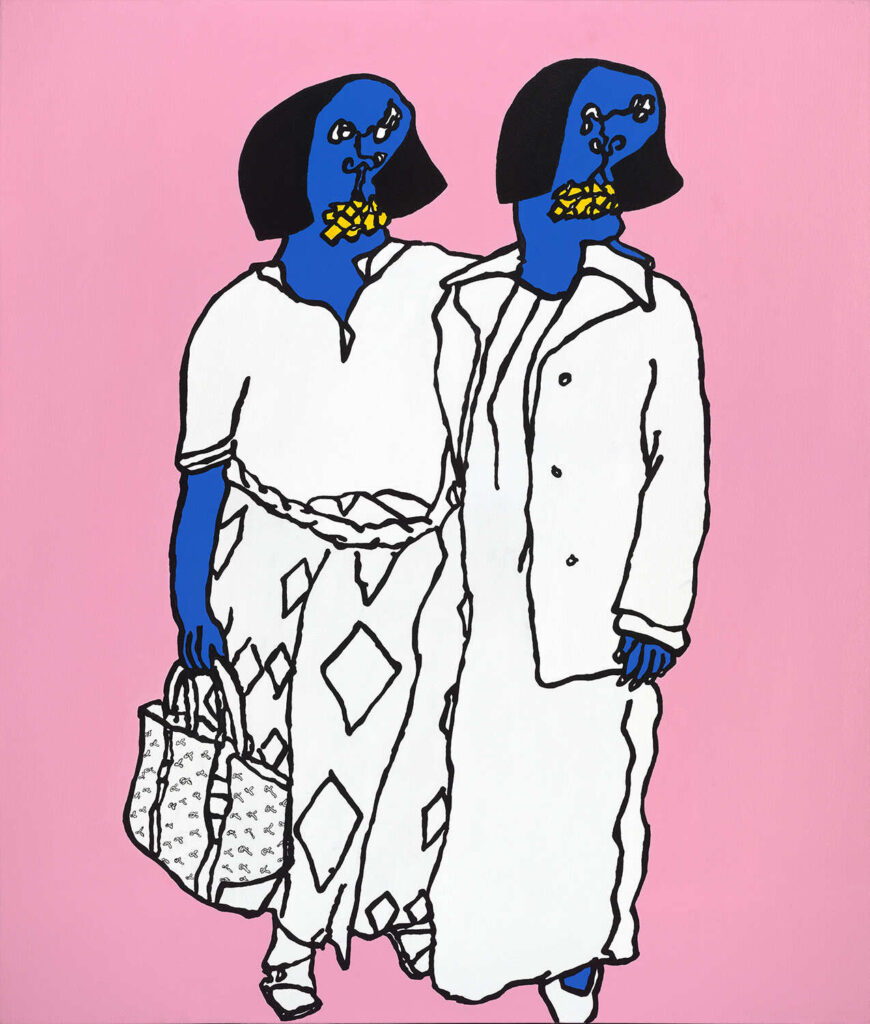

I love your painting, ‘Prison Pink’. Is it titled as such to reference “drunk-tank pink”? Can you tell us about this piece and the meaning behind the title?

‘Prison Pink’ uses the colour pink to explore the concept of confinement. In Rwanda, the pinkish attire marks the incarcerated, a visual cue of imprisonment. Here, the subjects are entirely enveloped by pink, symbolising how refuge can morph into restraint. It reflects on refugees’ reality in places like South Africa, where the search for safety can lead to a new form of restriction, confined to a single place, their movement and freedom paradoxically limited in their newfound ‘home.’

In ‘Still a Long Way to Go’, is this based on a photo of your friends and family? If you use a photo reference, how much do you veer away from the original arrangement of people?

In creating ‘Still a Long Way to Go’, my approach has evolved from my earlier practice. Initially, I closely followed old family photographs, maintaining the original arrangement. However, for this piece, I combined a found image with poses from my siblings, allowing me to deviate from the original to achieve the desired composition. This method of blending different sources is integral to my research phase, often involving editing and altering online materials to serve as reference, ensuring each artwork embodies the narrative and aesthetic I aim to convey.

…I’m open to incorporating other mediums like oil paint in the future, as my journey in art is one of continuous experimentation and growth.

Jean Luc Iradukunda

I see one of your media used is markers. What type of markers? What is it that you like about acrylic paint?

For my marker work, I primarily use POSCA markers and Montana water-based markers. As for acrylic paint, my practice is grounded in exploration rather than a specific preference for any medium. Acrylics have been a valuable tool in my artistic development, offering versatility, a rapid drying time, and ease of availability. While I appreciate these qualities, I’m open to incorporating other mediums like oil paint in the future, as my journey in art is one of continuous experimentation and growth.

Please tell me about the piece ‘Building What We Will Destroy’.

‘Building What We Will Destroy’ contemplates the bittersweet process of building up lives in one’s homeland, akin to the traditional Rwandan Runonko making, where a dome of clay balls is constructed and heated before being collapsed over food to cook it within. It reflects on how migrants often contribute to the fabric of their nation, crafting and shaping their community, only to leave behind their handiwork—knowingly or unknowingly stirring the undercurrents that may lead to its unravelling. This piece captures the duality of creation and loss, the investment in a home that is both vital and ephemeral against the tides of migration.

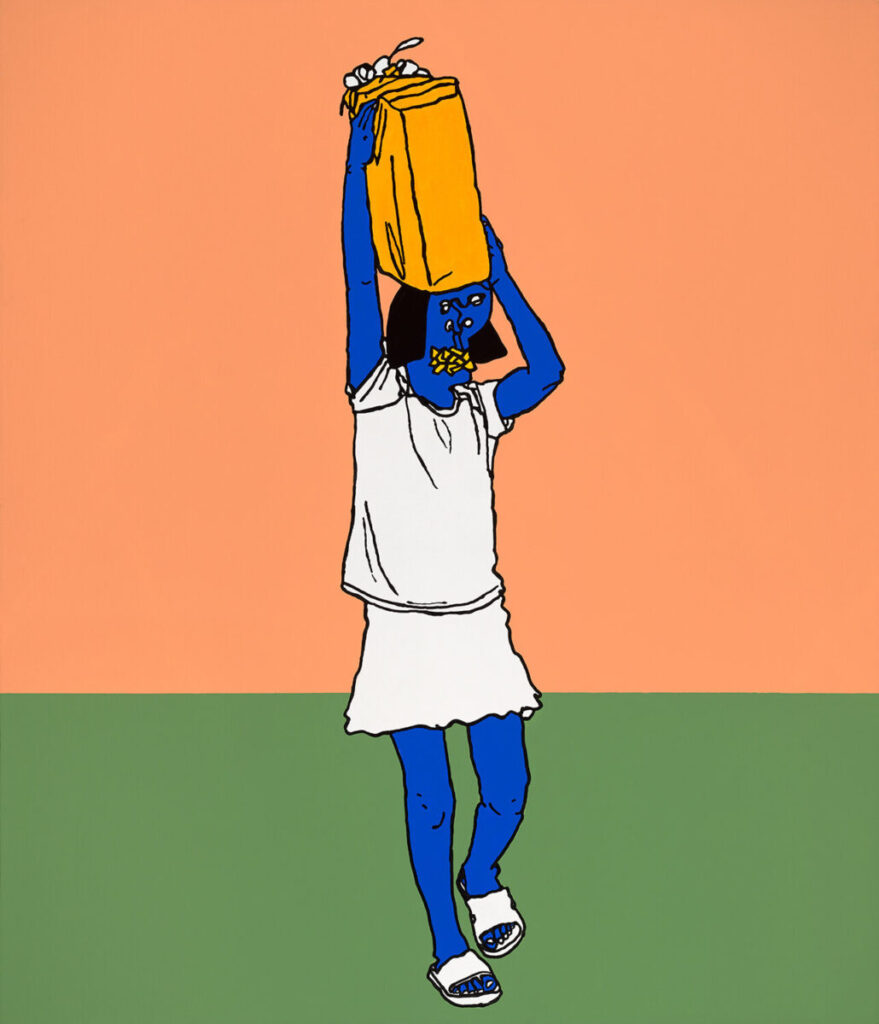

In ‘Fetching Water’, is the tradition of head loading something you experienced within your own family or town?

Indeed, ‘Fetching Water’ is rooted in my personal experiences growing up in Mukarange, in northern Rwanda. As a child, we lacked direct access to running water, so fetching it from a communal pump was a regular and necessary part of daily life. This artwork is a reflection of those early, formative experiences. This piece deliberately steps away from the migration narrative to ground itself in the joyous and untainted memories of home. The figure, centered and steady, carrying water, represents a moment captured in time where the simplicity of the task is a source of delight, and the journey is as meaningful as the destination. It is a celebration of the mundane transformed into the memorable.

With most of your works, even though the clothing is absent of colour, I’m drawn to what the figures are wearing. Are you inspired by fashion?

Absolutely, fashion does inspire my work. Initially, it was a casual appreciation through social media, but my interest deepened, especially during Virgil Abloh’s influential period, when I developed a fascination with graphic t-shirts. This passion for fashion led me and some friends to start our own clothing brand, CHANT RADIO, where I have the opportunity to design t-shirts and express my artistic vision in a different medium.

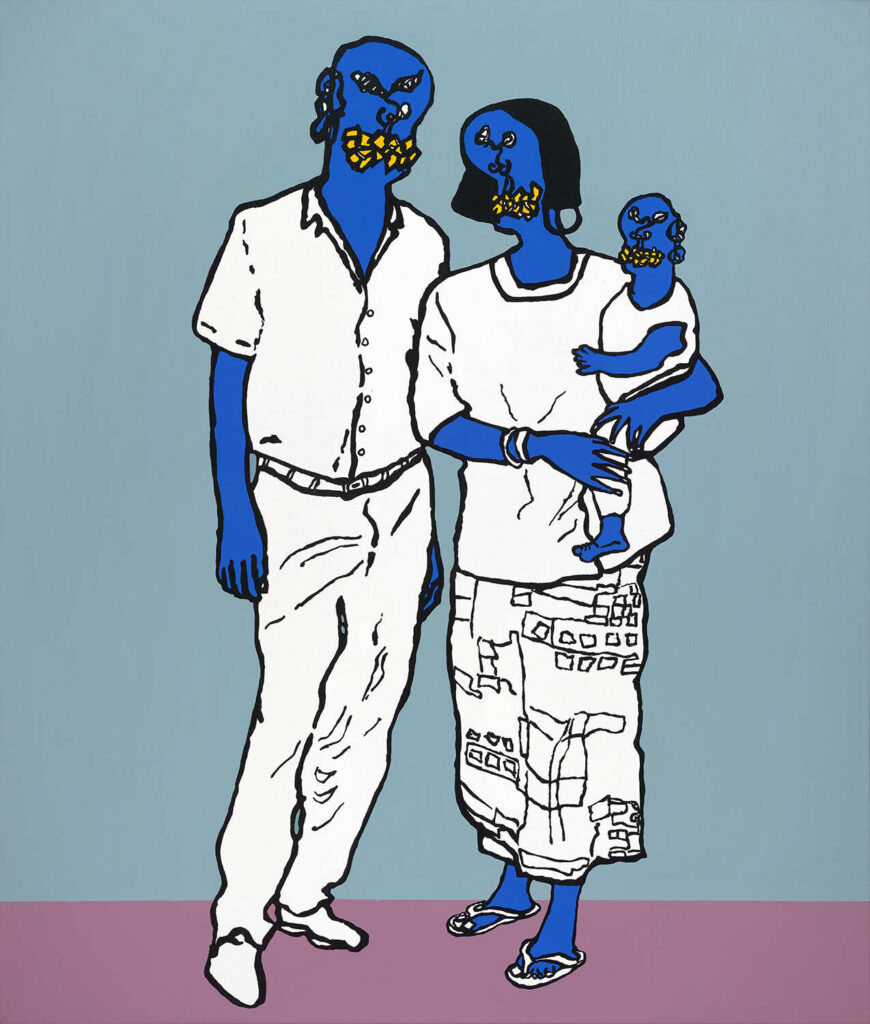

Can you tell me about the painting ‘Igitenge’? Does that word have to do with African fashion?

It goes by many names in other parts of Africa, but in Rwanda, we call it ‘Igitenge’. These fabrics are known for their bold patterns and African-inspired designs. Besides being worn casually and ceremonially, mothers often use them to carry their babies, offering a sense of safety and comfort. When I began the painting, the focus was on the scene which depicts my father, mother and elder brother in a refugee camp years before I was born. I wanted to focus on the ‘Igitenge’ my mother was wearing as a juxtaposition of safety and comfort that it can provide and the stark contrast of the reality that led them to being in the refugee camp.

I wrote down somewhere in my journal that my work in these past few years has been strongly focused on how I felt perceived by the world and that I’d like to pivot towards making works that are about how I perceive the world.

Jean Luc Iradukunda

What are three words you would use to describe your work and why?

Experimental: This word embodies the exploratory spirit of my process. Not knowing exactly what I’m doing frees me from conventional restrictions and allows for authentic creation.

Probing: My work is deeply rooted in research, reflecting my reverence for the privilege of exploring and expressing my understanding of the world as both native and outsider through art.

Evolving: I dream that my artwork never becomes static; it’s always in progress, mirroring my ever-expanding grasp of the world around me. I want my work to suggest a journey rather than a destination, to produce objects that are perpetually becoming as I am.

Lastly, what are you currently working on and what are your goals for the year?

I wrote down somewhere in my journal that my work in these past few years has been strongly focused on how I felt perceived by the world and that I’d like to pivot towards making works that are about how I perceive the world. My goals for this year involve exploring more mediums – sculpture holds particular appeal right now – and oil paint, among others. I’m also aiming to secure a solo gallery exhibition.

Check out Jean Luc Iradukunda’s available work here: Bender Gallery!