Bernini, a great sculptor of the Italian Renaissance, carved his Ecstasy of St. Teresa as a masterful depiction of a woman in orgasm. Yet he would never have admitted that sex was his subject. Dominating Rome’s Cornaro Chapel the sculpture is said to represent a sacred moment, the instant the spirit enters the flesh. For 350 years, however, people have been writing about its obvious eroticism.

What does this have to do with Sophia Narrett? The Ecstasy of St. Teresa is a vivid example of the general impulse of art and pop culture that she is questioning. People are always using non erotic episodes from life to create veiled references to sex. Narrett turns this idea inside out. Her embroidered art often shows explicit sexual acts as a way to contemplate the not necessarily steamy parts of life.

I first saw her work in the show titled SEED that I reviewed for Beautiful Bizarre Magazine this summer. Now seems like a good time to dive deeper into her art since she has work at the Museum of Art and Design in Manhattan, a show at the Mindy Solomon Gallery in Miami, and another group show coming up at Marinaro, in Manhattan. We met in her Brooklyn studio to talk ideas and look over the threads.

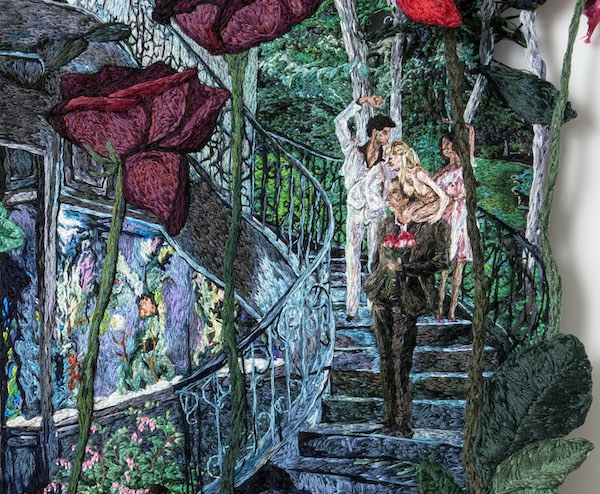

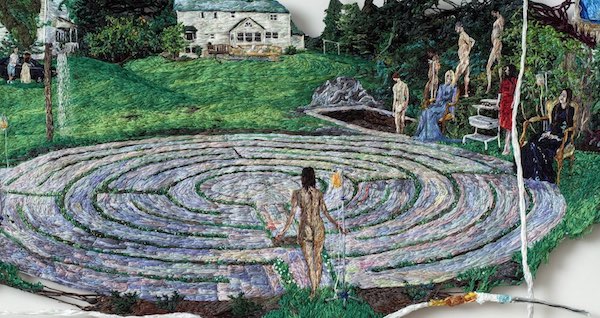

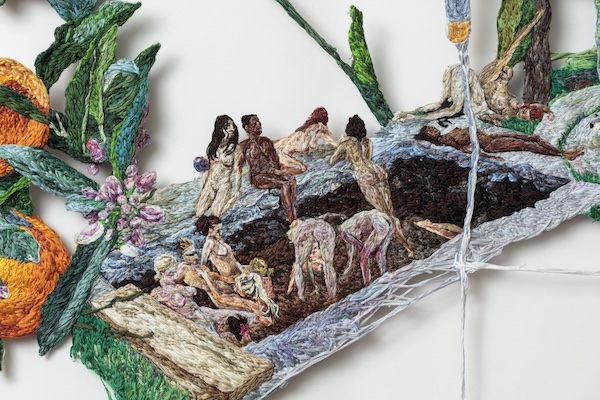

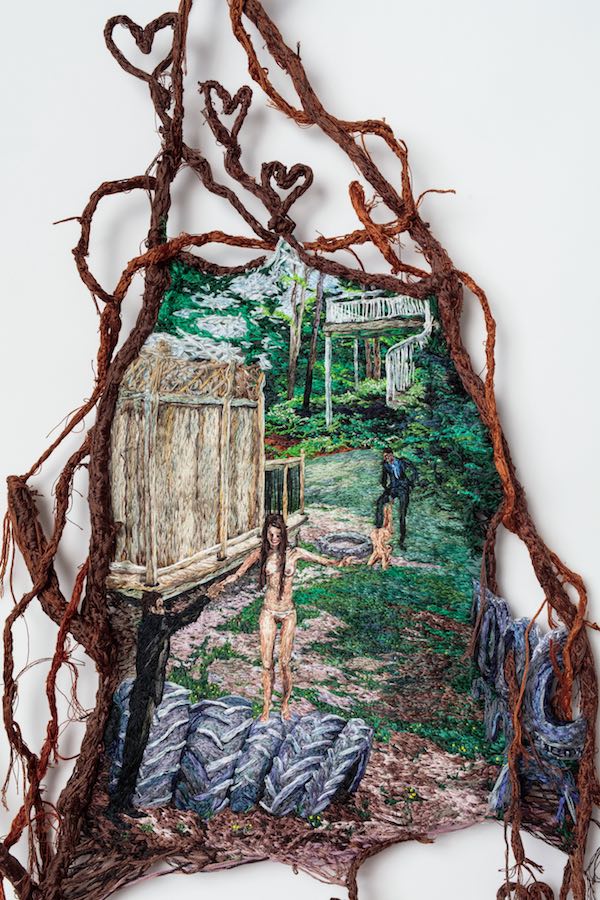

Before going into that, however, I should describe what it is like to approach her art. At the Museum of Art and Design her massive piece titled “Right Before” hangs in a show of recent acquisitions called “The Future of Craft”. This 82”x26” embroidered work keeps company with art by some very big names such as Sanford Biggers, El Anatsui, and Judy Chicago. As you approach the organic shape on the wall the lush quality of color and the startling illusionistic effects of the architecture and landscape depicted are the first things that jump out at you. Then you see the unbridled erotic and transgressive acts embedded in the fibers. To the uninitiated the central part of the work looks like a heaving orgy of about fifteen women. It is neatly surrounded by a circular staircase and balcony which are in turn framed by lovingly executed floral motifs that return the viewer to the world of expected and traditional needlework. The staircase and background are populated by characters and things of some undecipherable meaning. At the top of the stair men clothed like production assistants sprinkle rose petals on a couple engaged in a marriage proposal, the male on bended knee. Down the stairs dance the disco figures of John Travolta and Karen Lynn Gorney from the movie Saturday Night Fever. Partially obscuring them is a man in a suit with a nude woman on his shoulder, at the foot of the stairs a woman pisses into a hole. Aquariums and computers showing graphs occupy the background which also features a woman peeking in on the tangled figures on the carpet and a man punching a wall in evident anger.

Current and Upcoming Exhibitions:

Museum of Arts and Design, Manhattan, NY “The Future of Craft Part 1” through March 31, 2019

Mindy Solomon Gallery, Miami, FL “Close the Blinds” through November 24, 2018

Right Before (detail), 2017-18, Embroidery Thread, Fabric, Aluminum, Approx 82 x 26 in.

Right Before (detail), 2017-18, Embroidery Thread, Fabric, Aluminum

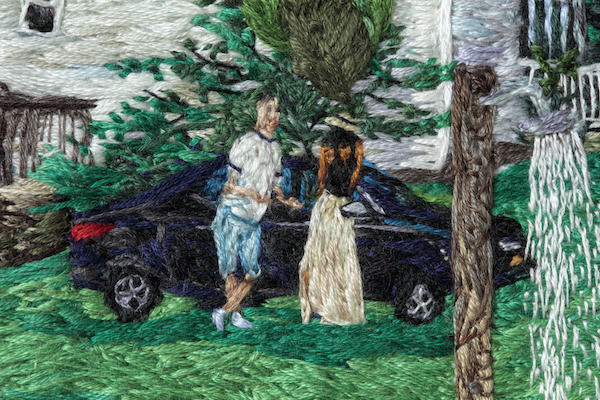

Right Before (detail), 2017-18, Embroidery Thread, Fabric, Aluminum

To decipher the figures on the floor you have to lean in close to the entwined filaments in order to make out where one body ends and another begins. What these characters are doing is invariably wanton. They and the other people shown are depicted is a fashion that alternates between representation and distortion. Arms become ropey and features cartoonish in the artist’s quixotic quest to render outrageous complexity via colored strands. The entire work fluctuates between vibrant illusions and a determined tactile stringiness. The flesh tones are various. No simple peach or brown here! Purple, blue, grey and green give dimension to the human figures while still conveying naturalism. This nuanced approach to the hues of skin call out the artist’s background as a painter.

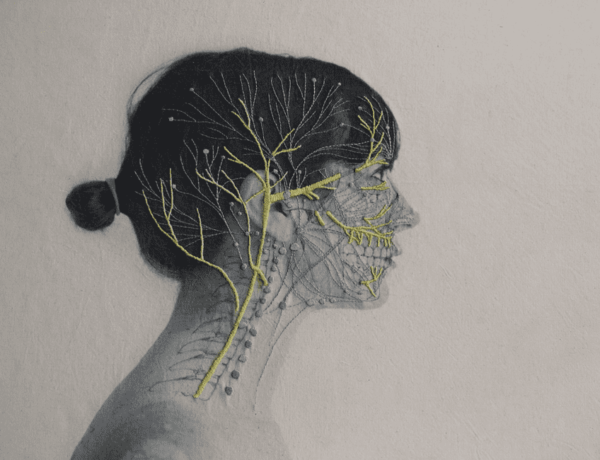

Prior to discovering the superiority of needle and thread Narrett had indeed spent years producing figurative works on canvas. She took the leap into the new medium after seeing the exhibition “Unmonumental” at New York’s New Museum in 2008. That show featured artists working in unconventional materials with attitude and ideas prized over craft or skill. At the time Narrett had been drawing on doilies. She thought to experiment with string. After three forays into forming her ideas via thread she found her current voice. Embroidery was a gift. It forced her to slow down and limited her color options. Even though she now uses as many as 500 hues in a work this is less than the variety one can mix on a painter’s palette. She says these kinds of limitations can force one to make interesting decisions. The medium also constrains the way shapes are made and limits the level of resolution possible. Each color is the thickness of a fiber, it must be made of lines rather than mass. The artist can only get detailed to a point and the cords are structural, they aren’t dabbed onto a canvas they are stuck through and tied into each other. Yet the hues employed remain forever fresh. They never turn muddy or deadened by touching and retouching. And revisions are an important to this Narrett. Sometimes she will cut out a section out of an image if it isn’t going right. In all cases she painstakingly laces layer upon layer to get things right. Over weeks or months the webs become so thick they can stand up on their own when removed from the hoop.

In deciding her way of working, she followed a path of personal meaning rather than a worship of either craft or art historical context. Only after starting to embroider did she seek any technical knowledge. Only after committing to filaments did she look into the history or the feminist craft movement of the 1970’s with its deep attachment to fiber art. In some ways she continued to think and act as a painter. It is kind of outrageous that she was working entirely in embroidery when she enrolled in the painting program for a Master’s Degree at the Rhode Island School of Design. Her primary artistic influences continue to be painters, with her favorite contemporary artists including Allison Schulnik, Lisa Yuskavage, and Angela Dufresne who she studied with at RISD. Of historical artists Hieronymus Bosch is a touchstone.

With time the viewer’s impressions shift from a soft shock at the erotic strings to become more of a wonder at the riddles posed by the work. There is earnestness to her symbology that makes it seem as if the artist is truly trying to speak some impossible language. No doubt comprehension is waylaid, in part, because of the unconventional use of explicit sexual acts as symbols for things that may have nothing to do with sex. As important as symbols are to her work Narrett believes it is vital to leave them largely unexplained. One metaphor she is willing to talk about is the circle of interwoven women in “Right Before”. To her these figures represent only an absolute happiness. Having that one foothold of meaning does help the viewer see this collage of sexual tensions as possibly representing something larger.

In a world of super-available porn, perhaps it is logical to reuse erotic imagery to tell stories about one’s internal psychology and mythology. Most people are afraid to even discuss the way these kinds of pictures are so accessible and dominant on line. Yet they are undeniably a currency of communication that is widely used alongside other, growing trends like erotic literature. Websites like bitchtopia.com are ever on the rise, and as they become more mainstream begin to raise the same questions that erotic art has asked for centuries, such as where does the inspiration stem from?

Narrett is candid about where she gets her figures. Tumblr is her main source. It is part of the meaning of her work to incorporate asocial images from the cold blue screen into her highly tactile private narratives. A work such as “Right Before” takes as long as eight months. With her repeated handling of the material and her obvious love of the human figure it seems she can transform the alienated source photos into something representative of a steadier and caring human contact.

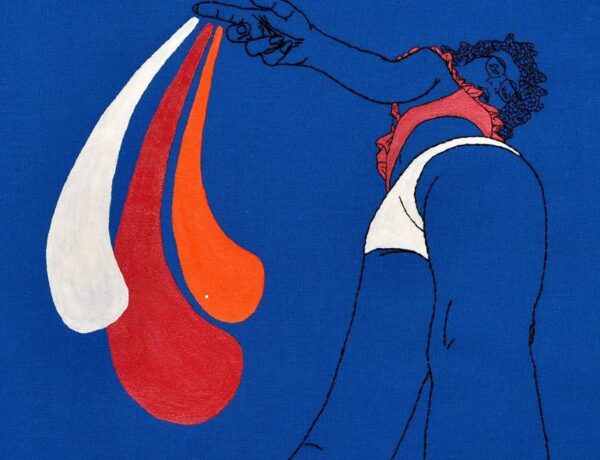

Stuck, 2016, Embroidery Thread and Fabric

The artist is not blind to the titillation factor that makes her art so readily shared on social media. This is a happy secondary effect of dealing in visions of the sexualized female. Yet the power of the erotic is important to the artist in other ways. Explicit depictions help her focus on and delight in her work. In the private story world that is the real subject of what she is doing these images are vital. Among other things they serve as the implied culmination of so much of of pop culture. We are swamped with love stories. Renditions of the act of human pairing wash over us continuously, you don’t just have to be on sites like hdsexvideo. Just watch anything from the TV series “The Bachelor” to any Hollywood blockbuster. Everything has a love story. Narrett’s enigmatic graphic language is, for her, often about pulling together a means to get above that miasma. The figures give her a way to reimagine possibilities amidst the this onslaught of the romantic.

The culture of the 1970’s plays a roll in her work as well. Her motifs include tie dyes, disco dancers and a certain style of floral print. Perhaps that decade is important as the first flourishing of our ongoing sexual revolution. Emily Colucci wrote a great article about Narrett’s work and its ties to the 70’s in the journal Filthy Dreams.

That decade also saw a flowering of interest in Eastern religions. Is it a coincidence that Buddhist and Hindu traditions provide ancient examples of artists using explicit imagery in a ways could be said to parallel Narrett’s approach? In the artist’s studio the Tibetan vision of Kachod Karmo came to mind. It is very much like several of her characters. The religious figure has her legs up behind her arms and her genitals are emphatically on display. As with Narrett’s work this representation of the body is supposed to be more than pornographic. The Kachod Karmo is meant to help the mind focused on the transformation of the self at the time of death and rebirth. It can also be seen as a call for discipline. Any sexual energy inspired is to be felt and understood as part of the life force of reincarnation. Then that energy is meant to be channeled toward building compassion and a higher consciousness.

What do Narrett’s embroideries achieve when they use a similar figure? There are many directions one could go in trying to answer this. What if we were to dive deeper into the idea of personal myth that she says is one of her central concerns? Then the question becomes an inquiry into the social role of cryptic narratives. This is a fruitful direction to explore because this is a huge issue that applies to a lot of art now. We are witnessing a massive surge of artwork that uses enigmatic personal symbols. What is it all for?

There are obviously a lot of answers to such a question. However one speculative thread could tie this all together.

Some artists strive to transform their lives through the images they make. For these artists their work is like an incantation. The artist discovers symbols of profound personal meaning. They rearrange these symbols to create ideas of pathways through life, visions of desired outcomes. Then, when making art from the resulting arrangement they contemplate the importance of the symbols from many angles. A generous heart is brought to bear. Whether the metaphors are positive or negative to begin with they all become intertwined into a thing of visual fascination. In this way an artist can riddle out their situation and bring a greater sense of beauty and comprehension into their life. The artwork could be said to be the the guide by which a vision of the future became real. When an artist uses this particular process the resulting artwork is like an illumination of how the ethereal can become material. The work becomes a map showing a path by which one can make the spirit enter the flesh.

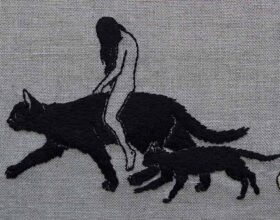

Stuck (detail), 2016, Embroidery Thread and Fabric, Approx 62 x 38 in.

Stuck (detail), 2016, Embroidery Thread and Fabric

Stuck (detail), 2016, Embroidery Thread and Fabric

Text, 2018, Embroidery Thread, Fabric, 12 x 7 in

Heart (detail), 2018, Embroidery Thread, Fabric, 7.5 in x 25

6PM (detail), Embroidery Thread, Fabric, and Aluminum, 2017

Ask Again (detail), 2018, Embroidery Thread, Fabric, Aluminum, 16 x 33 in

Pin, 2018 Embroidery Thread, Fabric, 9 x 8 in