“Gulls wheel through spokes of sunlight over gracious roofs and dowdy thatch, snatching entrails at the marketplace and escaping over cloistered gardens, spike topped walls and treble-bolted doors [….] Gulls alight on whitewashed gables, creaking pagodas and dung-ripe stables; circle over towers and cavernous bells and over hidden squares where urns of urine sit by covered wells, watched by mule-drivers, mules and wolf-snouted dogs, ignored by hunch-backed makers of clogs; gather speed up the stoned-in Nakashima River and fly beneath the arches of its bridges, glimpsed form kitchen doors, watched by farmers walking high, stony ridges […] over the roof of a painter withdrawn first from the world, then his family, and down into a masterpiece that has, in the end, withdrawn from its creator; and around again, where their flight began, over the balcony of the Room of Last Chrysanthemum, where a puddle from last night’s rain is evaporating; a puddle in which Magistrate Shiroyama observes the blurred reflections of gulls wheeling through spokes of sunlight. This world, he thinks, contains just one masterpiece, and that is itself.”

– David Mitchell, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet

Under the Tokugawa Shogunate, there was a period of Japanese history known as Sakoku. This was a period that arguably provided stability for Japan but at the cost of over 200 years of isolationist foreign policy. For better or worse, the effect of this policy was, in essence, the banning of all western influences, from artistic, religious and philosophical expression. Nonetheless, there were exemptions for commerce with the Dutch East India Company and for a limited period, the English, which provided the opportunity for such contraband to filter through to Japan.

Under the Tokugawa Shogunate, there was a period of Japanese history known as Sakoku. This was a period that arguably provided stability for Japan but at the cost of over 200 years of isolationist foreign policy. For better or worse, the effect of this policy was, in essence, the banning of all western influences, from artistic, religious and philosophical expression. Nonetheless, there were exemptions for commerce with the Dutch East India Company and for a limited period, the English, which provided the opportunity for such contraband to filter through to Japan.

With the signing of the Convention of Kanagawa and the restoration of the Meiji emperor in 1868, an unprecedented period began in Japanese history: borders were washed away and western culture flooded into the harbors of Nagasaki and the like. Over time, fears arose about the influence the western world was having on the Japan and thoughts emerged in more conservative thinkers that the Japanese art style would drown and in its place western art would rise. It was this catalyst, which provoked the emergence of two broad schools of Japanese art: yoga, which adopted the oil painting of the west and nihonga, which focused on the traditional Japanese techniques and materials. More progressive schools of thought suggested that nihonga was developed as a way to distinguish the styles each artistic expression brought, rather than a movement motivated by fear; it was to highlight the more minimalists beauty found in traditional Japan art form.

If this aspect of Japanese history interests you, I thoroughly recommend David Mitchell’s historical novel, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, as it provides a wonderful insight into the tensions between the Japanese authorities and Western traders.

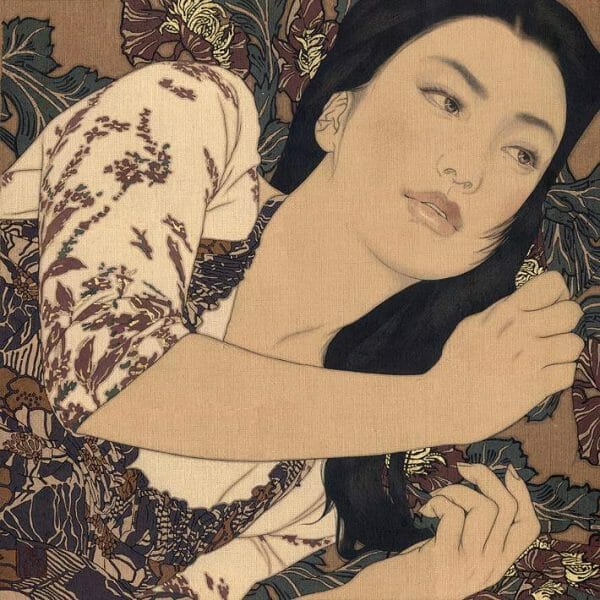

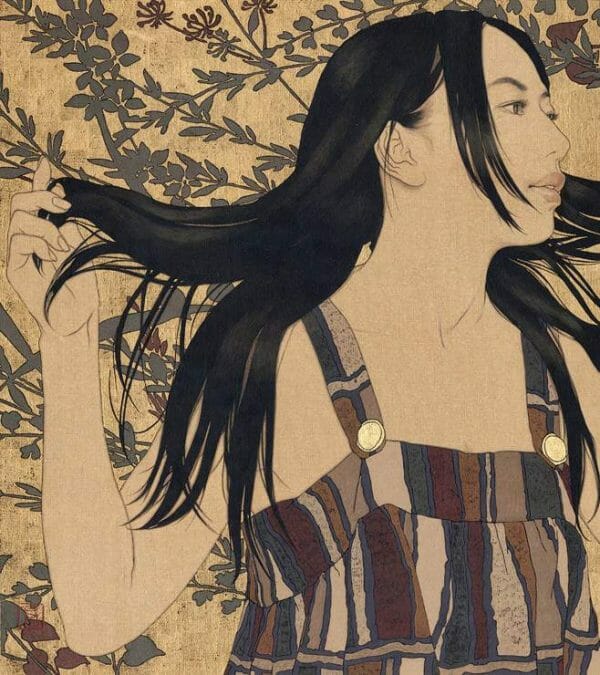

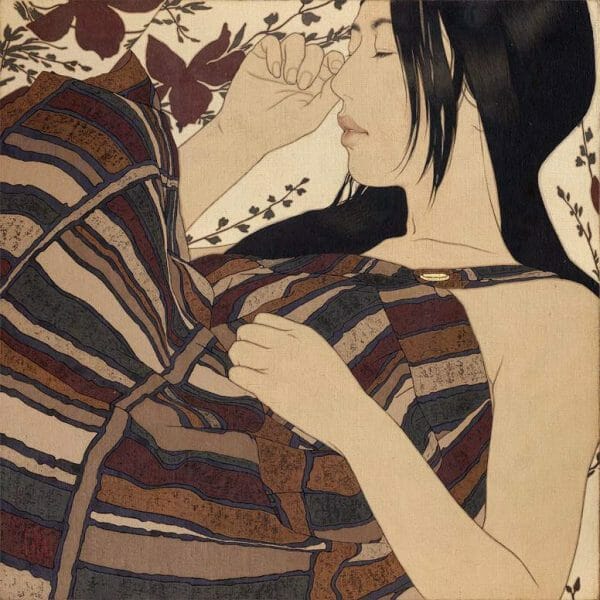

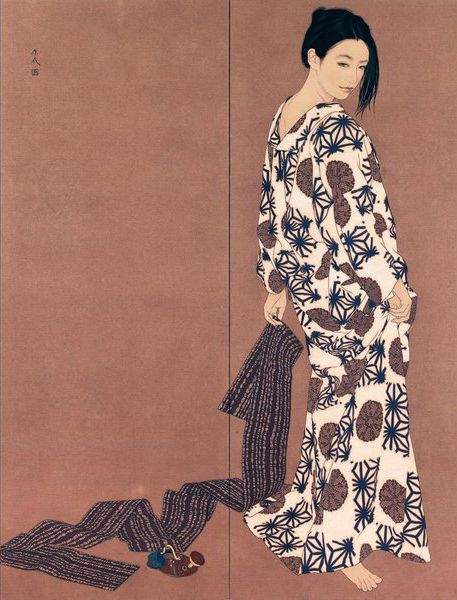

It is this nihonga style that Ikenaga Yasunari gravitates towards. The American art philosopher, Ernest Francisco Fenollosa, who taught at Tokyo Imperial University during this influx of art, identified the following qualities of nihonga style:

- The absence of realism

- The absence of shadow

- The presence of outline

- The absence of a rich palette

- The expression is simple

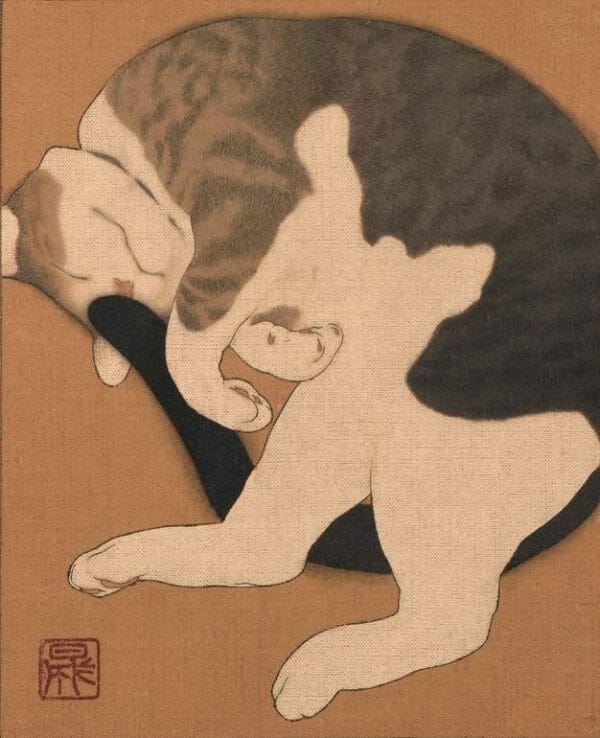

The question was posed by many art philosophers of the time: what does the nihonga style provide in terms of artistic expression? Does it add anything to western styles? Well, it seems that Ikenaga’s paintings toy with this question somewhat by poke-fun at the idea that nihonga has to prove anything in particular – with its influence thought to have originated from Korea and areas of China, like many art movements, it is an amalgamation of styles and influences. Ikenaga and artists of his ilk show that nihonga provides space for the subject matter to breath, with its influence seen throughout the artistic world, from illustrators to modern cinema. Ikenaga still uses the traditional materials that give nihonga its origin – sumi ink, line canvas, mineral pigments, which are applied by way of traditional ‘fude’ or ‘hake’ brush. But where Ikenaga’s traditional school meets modern Japan and western styles, is in his modern stylings and clothing patterns of his female muses that are sometimes accented by gold leaf. Ikenaga’s art holds true to many of the traditional nihonga qualities, even the gold leaf does not detract from this; while metallic it still complements the soft palette. You can also see elements of art nouveau in the style of pose and decorative nature of the dress.

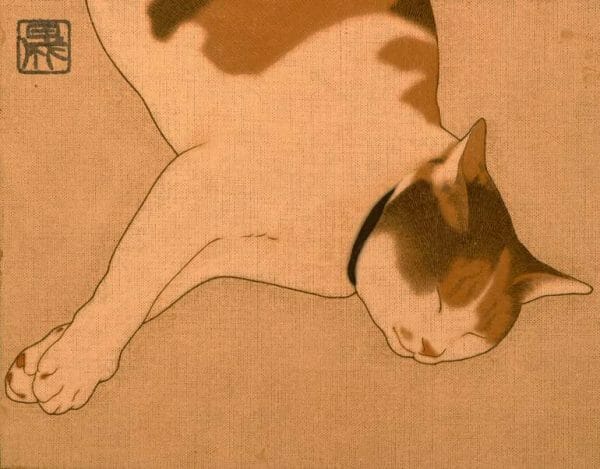

Brushstrokes sweep down the Tokaido road that is the line canvas, whistling through foliage and material, blooming and entwining with jet black hair and elegant patterned dress; there’s even a cat or two. I give you the modern Japanese women of Ikenaga Yasunari.

|Website|