At first glance, artist Miho Hirano springs from that stripe of art most frequently found in ‘anime adaptations from the original manga’. You heard me – Vampire Hunter D, Ghost in the Shell… Naruto. Quite out of step with the opinions of anti-anime art aficionados and instructors, you may have heard on YouTube, Hirano’s style is spellbinding and fiercely unique. She thrives far from the madding debate about the legitimacy of anime-influenced artists. Still, something about her art always made me stop and wonder.

What was up with her heroines’ hair? And, by that, I mean I often studied her creations as works of beauty and tension, but I struggled with what Miho’s trademark hair might mean.

Where did the concepts for such original treatments of hair, which is at once, common, and yet very culturally loaded – particularly for women of colour – come from? Watching the evolution of her artwork, that question became inescapable: Is it simply beautiful? Or had this impetus grown from something deeper?

My first impulse was to connect the floral nature of Miho Hirano’s characters to reclaiming a confounded notion of womanhood, like women’s closeness to nature, their connection to the moon in myth and body, and painting them as entwined with untamed things. These notions had been misused to oppress women for centuries, and I think them well-worth recovering and properly defining in the modern age. However, I couldn’t look into the eyes of her works and square-up around that notion either. There was something more going on.

It’s not possible to peek into the creative cauldron that is Miho Hirano’s mind, but there’s a historical context into which the locks of these unapologetically new-fangled paintings fit, and it’s surprisingly traditional.

Hair has a long history in Asian cultures. Traditionally, hairstyle linked to social statuses so that it earmarked where (and whether) an individual fit in their community. And it was even more influential because it sunk its taproot into the prolific soil of virility, desire, death, and mysticism.

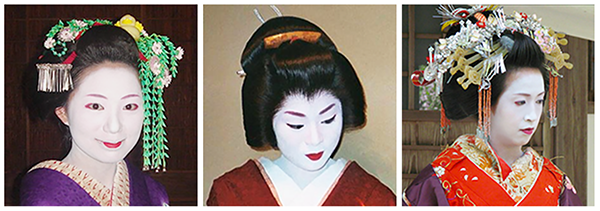

Hair was a big production! Don’t believe me? Consider the hairstyles of modern geisha, in specific that of Maiko (the apprentice geisha), Geiko (the experts), and of Japan’s historic courtesans called Oiran (not geisha at all, but once powerful prostitutes). It used to be that, while you waited on your time with a Courtesan, Geiko would keep you company. They were skilled artists and keen conversationalists, good at keeping customers jolly.

Maiko, with their bouncing, jingling hair ornaments, are decorated to look cute, pretty; Geiko pare down to sleek hair shapes and chic ornamentation, and are elegant; the average Oiran had enough come-hither headdress to bury a man alive! They were meant to look luscious and extravagant. Each hairstyle advertised something about the girls or women wearing them. But in all cases, the hair is painstakingly groomed, shaped, and ornamented.

In contrast, loose hair was thought, particularly of women, to be dangerously uninhibited. Nodding at disease or dementia, alive with sexual appetite or supernatural power, wild thoughts were the province of wild hair. It could be hazardous because, as a symbol of youth and vitality, unbound hair crossed the line between fertility and civilization’s long plunge into abandon.

Miho seems well-aware of the importance of the hair she paints, and often captures her heroines in a moment of transition. In ‘Release’ below, you see the heroine’s hair flip up as flowers spring, irrepressible, from under it. It’s beautiful. And it carries a hidden cultural payload. Not only is this hair unbound and wild, it’s grey. If solidly black hair is associated with life-force and youth, white or grey are associated with age and death. Think of the white smoke of cremation, of incense, or other ritual fires. Her pale hair combines the ghostliness of mortality with the unnatural fecundity of cherry blossoms pouring out all over.

This is because Miho’s girls have one foot planted in the mortal world, and one stretched across to a divine shore.

I soon found Hirano busting through old philosophies as well. The opposite of free, flying hair is to carefully style and bind it as geisha do, or tie it up, safe and sound, into a modern-style braid. Even sacred shimenawa ropes used to purify shrines and torii in Japan, always resembled orderly hair braids to me. And then there’s Miho Hirano…

Quickly laying waste to that mythology, Hirano makes it clear that, while hair is powerful and has its own stamp of divine potency, the most unstoppable and irrepressible force about it is the girl underneath.

Quietly, she’s the power. Her choices are the source of the tension and temptation in the world around her, and braiding and binding her wagging hair will not avail you!

No less than any other culture, the Japanese must have noticed the apparent ability of hair to grow longer after death. Today we know that dehydration leads to tissue shrinkage and, as the flesh pulls back, this causes the appearance of the growth. But back then, the fearsome power and vitality of hair proved its dominion by outlasting even the life of the body. As such, some part of it remains linked to the divine. It may be the peek into that history, as well as the redefinition of that narrative, that breathes life into Miho Hirano’s art, and makes it timeless.

If you can’t get enough of Miho Hirano, follow her artsy adventures on Facebook, Instagram, or on her website!