Jack of the Dust, otherwise known as Andrew “Andy” Firth, transmutes death into life with his series of skullptures, handcrafted from the depths of Australia’s Gold Coast. His Jack of the Dust trademark, derived from maritime terminology, comes from “an obsolete US Navy job designation from the 1800’s; this person was the ship’s steward, who worked with the dusty ingredients of flour and biscuits.” Firth took the mostly retired name and repurposed it as Jack for the name of his skulls, and “dust” referencing their death symbolism.

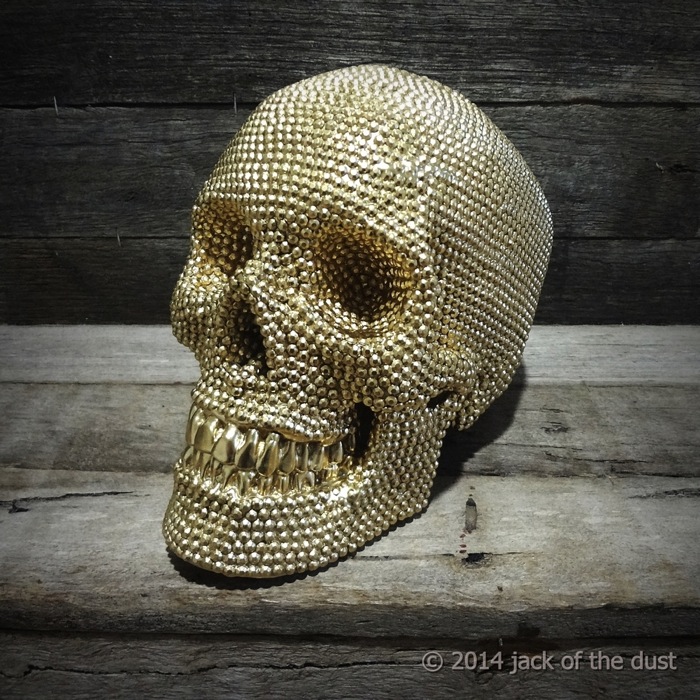

Bonsai gardens, cherry blossoms, bee hives and painted joker faces decorate the skull facades, which the artist says are “based on a premium European grad PVC plastic human anatomy skull, molded off a real human skull,” and “premium grade artistic variations of the human skull.” So no, the skulls are not real (I’ve been asked twice in the short period of writing this article) but they are as close to real as you can get.

His skullptures are visually stimulating, stirring works of beauty and craftsmanship, and the outcome is majestic, if macabre. The semiotics/symbolism of faux human remains are intriguing; we like the idea of death, we like to be as close to death as possible but only if it allows us to feel more alive – quite a paradox of living, I’d say.

The artistic replication of life-like skulls draws our attention to everything no one wants to talk about – at least in a very concrete, non-abstract way: death. Even in this period of skull fascination and popularity, what skulls represent outside of the artistic framework is, at their most raw and basic form, a direct correlation to our own mortality. In this way, Jack of the Dust’s skullptures allows us to see skulls differently. Death now breeds life, in the way of gardens and flowers and crystals. On the flip side, the skulls also turn into morbid, garish creatures and pop-culture icons, via villains like the joker and superheroes like Ironman. The most recent joker (played by Jared Leto in Suicide Squad) comes complete with an acid green stained scalp, bomb-smoked eye sockets, and two rows of grittily gleaming silver teeth. For Game of Thrones fans like myself, there’s White Walker Skull and the Obsidian Dragon Glass Skull.

Using the human skull as a platform from which to build, Jack of the Dust flips natural decomposition and converts it into creation, stimulation, and growth. Things literally appear to grow and move along the skullptures – Spring Bonsai Mountain Skull has a faux waterfall pouring out of an eye socket, which sits just below a bonsai garden with mossy grass the color of squeezed limes. It’s a visual representation symbolic of the circle of life – from death to life, and back again; and so the cycle continues, on and on, seemingly infinite. Jack of the Dust’s skullptures are a mortal varietal in amethyst crystals, gold dust and cherry blossoms, both exquisite and morbid, delicate and unnerving.

The mushroom garden in Down the Rabbit Hole is colorful and wild, and in Melting Gold Skull, the object comes to life, seemingly drowning in melted gold, jaw agape, screaming and re-dying in a molten hot fire of golden ooze. Okay, maybe a bit much, but it’s penetrating, jarring; it’s National Geographic and Pirate’s of the Caribbean meets haute couture performance art and macabre fashion.

This blending together of symbols and semiotic codes in the form of human skulls and artistic expression can take on a varietal of meanings, depending on the viewer and their perception of course. A diamond-encrusted skull, for example, seemingly innocent and dazzlingly brilliant, can take on a deeper, more social or political meaning, depending on the viewer and their frame of reference. Of course, you can see them as purely works of art, but nothing exists in a vacuum and semiotic code and image connotations are embedded into the core of which are thoughts are born. Again, it depends on your perspective. For me, I can’t help but take the symbology of the skull and form my own interpretations, but isn’t that what art is all about in the first place?

Here’s a morbid idea: Why not cherish our loved ones by turning their skeletal remains into works of art? Okay, maybe that’s a bit much, but it begs the question – why is it okay to have faux skulls and skeletons that are meant to look as real as humanly possible, but not okay to actually use real ones? After all, some people questioned that the skullptures here were made with real human skulls and didn’t bat an eye at the thought. I guess in the end, as long as they look real without them actually being real… that tiny fine line makes all the difference. We need the simulacrum.

In this way, using real skulls in artwork would seem a bit, I don’t know, morally skewed? Or would it? My curiosity drives on… Where is the fine line? What is too much, not enough, or too far? If Jack of the Death’s skulls were real, what does this change? What does this say about the value and meaning?

In an abstract way, and perhaps because of their intense popularity, the skull symbol has become so far removed from us. It has become completely and entirely abstract, ironically separated from us, when in fact, it is something that we literally carry around with us every single day; staring at a skull is staring back at your own self, only it’s what’s left of you after you’ve stopped existing. It gives us the creeps, and for good reason. But that’s why it’s a perfect symbol to use in art, for what is art but a means to talk about the “un-talkable”. We are constantly, since man has had a thought in his head, grappling with these issues of death and existence, so I think it’s only appropriate to fashion notions of life with what is perhaps the most notable and understood notion of death – skulls. It acts as a visual reminder of the cycle of life and death, and the importance of being able to find the beauty and wonder that is in both stages. Nothing is separate, everything is connected in some way, and beauty abounds in all things.