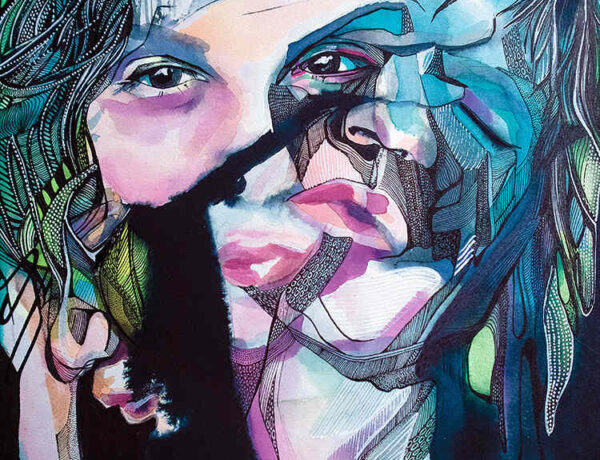

The horrors of war are unimaginable. To witness these atrocities through the pages of a library book or on a documentary on TV are one thing, but to witness it first hand is something else completely. Viewing Mikhail Ray’s photography brings a mixture of emotions bubbling to the surface. Feelings of pain, anxiety, worry and fear all strike into the consciousness as a fragmented reality unfurls. But alongside these emotions sit feelings of hope, courage and authentic human connection. His work not only tells the story of his life but also a story of how powerful, creative and resilient one can be.

Born in the city of Kherson, Ukraine, Mikhail Ray is a true testament to what truly striking artwork can form from our darkest moments. Mikhail has made it his mission to create art and document his own experiences to help inform the rest of the world what it’s actually like to live in Ukraine currently. After a 20 year career at sea, Mikhail traded in his sea legs for a camera lens deciding to live a more spiritual life. Since picking up a camera, Mikhail has been actively experimenting to develop his own unique style of photography that utilises digital collage. With the goal of “creating art that could awaken people”, Mikhail has captured the attention of many art lovers across the world all while continuing to share story as an artist can never be silenced.

My art tells the story of my life. As a rule, it contains both general ideas and specific experiences, especially in a war diary.

Interview with Mikhail Ray

I’d love to learn more about your artistic practice. How do you approach a new piece of work and what does your creative process look like?

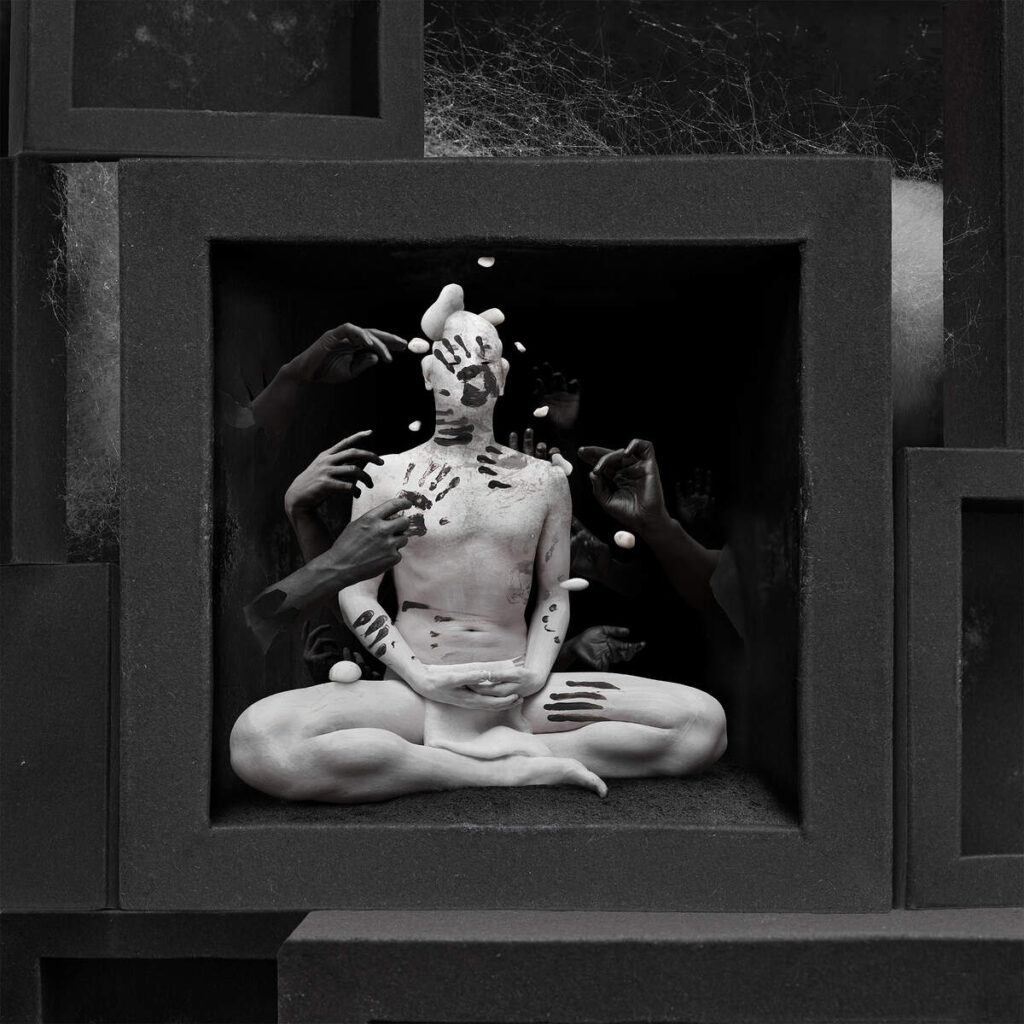

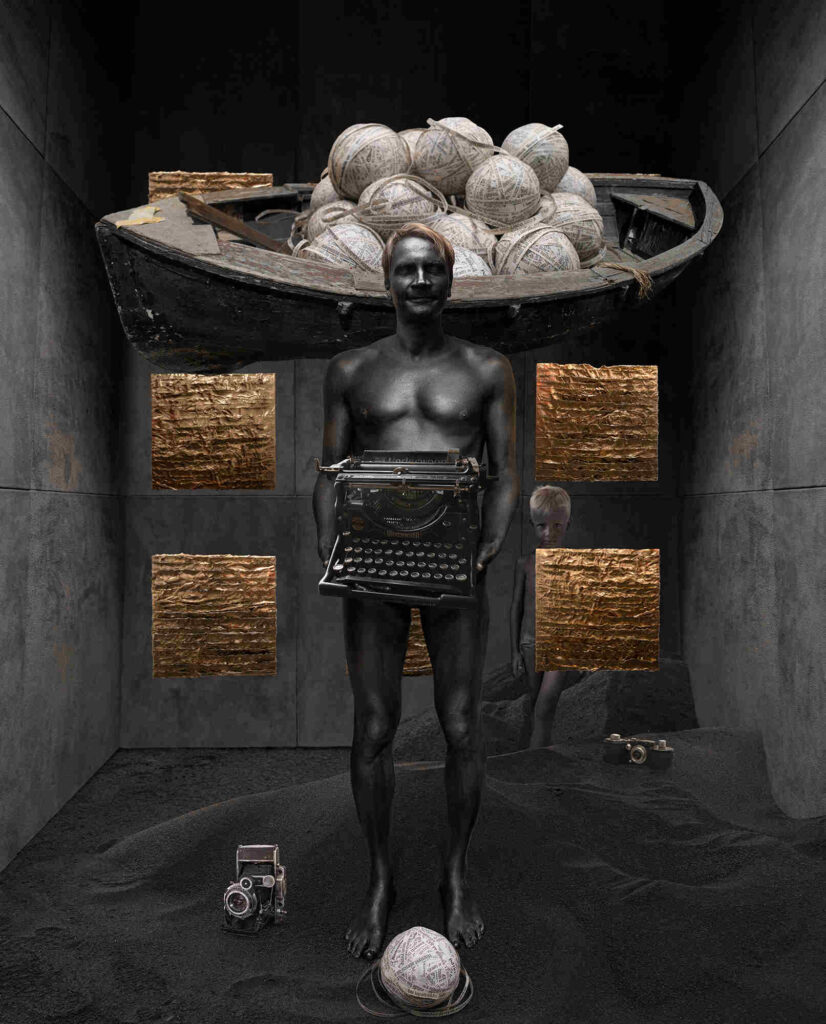

The longest and the most important stage is the internal one. It is also the most delicate, because it requires being in the right state of consciousness in order to capture those meanings and ideas that are “searching” for their creator. Meditation practices help a lot. When ideas arrive, I take my camera, tripod, flash and lenses and go to photograph all the elements of the future artwork. Sometimes I create them myself, in my home studio from stationery and a variety of various materials. And sometimes I ask my wife to paint my body from head to toe in black or white and help in shooting. The next steps are done in the software. Each element of the artwork is a separate photo, a separate layer with a mask, sometimes their number exceeds a hundred. The final stage is writing the concept of the artwork, its verbalization.

How long does a new piece of work usually take to make?

It all depends on the meaning and the number of elements in the artwork. Sometimes it takes a long time for internal analysis and synthesis of symbols, sometimes I need to work a lot with my hands, take pictures and create masks in the editor. I do not consider the artwork finished if I have not comprehended it and don’t understand what changed in me after its creation. There are things that can be quite difficult to bring to the surface of consciousness, so sometimes almost finished artworks are concealed for several years waiting for their turn. I suppose that on average it takes me two weeks to complete one artwork.

I understand that your work is infused with spiritual and philosophical meaning. What kind of beliefs and ideologies inspire you and your work?

At different stages, I was fascinated by the ideas of different people and different disciplines. Buddhist philosophers, mystics from both east and west, transactional analysis, psychology, spiral dynamics, applied kinesiology and many others. I cannot say that I am particularly inspired by any specific theory or beliefs. In a variety of religions, philosophies, I find a verbal expression of what I feel, the same truth, which people find in different ways and describe in different words and metaphors.

I’d love to hear about some of the techniques you use for your photography. What are some of your go-to techniques and what software/equipment do you use?

I photograph the objects in such a way as to convey details and textures as much as possible. Then I load it into Adobe Photoshop, which is the only editor I use, create a mask and continue to do this for each subsequent element in my composition. Sometimes what appears to be a single object in the finished artwork is the result of stacking many photographs as in panoramic photography or focus stacking, often used in macro photography. The process is laborious, but the result is an artwork that can be printed on a 2-metres long canvas, full of details. I came to the most optimal set of equipment in my portable Ray studio: digital SLR full-frame camera, lots of megapixels, a wide-angle 24mm/1.4 prime lens with good autofocus for any occasion indoors and outdoors and a macro lens 100mm/2.0, which works excellent for portraits as well. Plus a tripod, portable lights, high performance laptop and a Wacom pen display.

Art always tells a story. Are the pieces you create, especially your war diary series, based off of a particular memory or experience or do you create work from more generalised ideas?

My art tells the story of my life. As a rule, it contains both general ideas and specific experiences, especially in a war diary. My goal was describing the events that took place in occupied Kherson, and in many respects remained unnoticed and misunderstood for the rest of the world through my own experiences, as well as to convey my understanding of the war and its causes as an insider, through the prism of my life in the USSR and in independent Ukraine, as well as through ideas learned over the years of studying psychology, philosophy and religion.

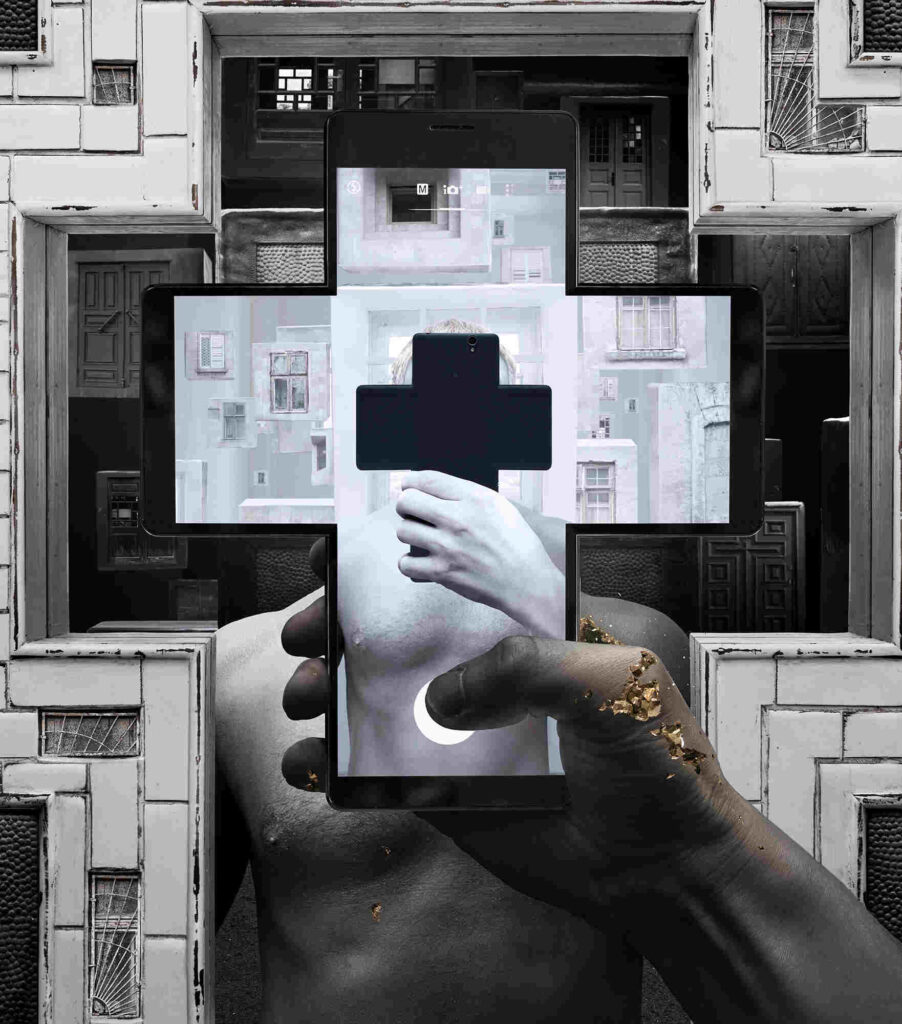

You discuss in your bio on your website how discovering digital photo colleges were the catalyst for your current body of work because you loved the idea of being able to create your own images. Would you say it’s like how an artist paints on a canvas versus regular photography?

Yes, exactly. I have more freedom and flexibility here. I am not only capturing my reality or constructing it. I am able to transform it. In some miraculous way, both myself and my life transformation follows.

When speaking of courage, it is impossible not to talk about fears.

Do you have any photographers or digital photo collage artists who have particularly inspired you?

I followed some artists for a while, when I studied Photoshop on my own and paid interest in techniques and possibilities of the genre. For quite a long time now, since I realised that there are no limitations for me, I have only observed artists with certain ideas and values, regardless of the way they are made. As for inspiration, I rarely draw it from other artists. Basically, I observe what is happening inside and around me and try to “hear”, or rather “feel” the moment, how people live, why people suffer and what we need now.

I understand that when Kherson became occupied by Russian forces you decided to stay in the city. How has your time in Kherson and the war impacted your outlook as an artist and the art that you make?

My experience in occupation brought me to rethinking my role as an artist and the role of art in general. Globally, my mission and scope of my interests have not changed, I am still dedicated to exploring myself, consciousness and its evolution in the human body. But since the beginning of the Russian invasion, I began to see many hidden phenomena with my own eyes and from my own experience. In many ways, life in war, and even more so, life under occupation, is the same peaceful life, but concentrated and accelerated many times over. All delusions, fears and erroneous actions that inevitably follow them reveal instantly and cost a lot more. Those things that would take decades to understand in peacetime, are gained in months in the occupation. My art now is much more focused on the needs of others. I believe that society needs an artist because he or she is able to perfectly express its feelings, thoughts and aspirations that have not found a way out to the surface of consciousness or support people where they need it. The artist has to be able to rise above the level where the problem was created and find the ways to solve it, perceiving events and phenomena with clarity. This is no longer a role, but a spiritual path. It turns the whole life of an artist into art.

‘The Storyteller. War Diary’ and ‘The Point’ not only work as incredible collections of art but also as intimate diaries and a glimpse into living through the Ukrainian war and your own personal thoughts, ideas and experiences. How does it feel to be able to share these deep and often intimate ideas and experiences with the world through both your artwork and your writing?

This is an unusual feeling. I tried to write even before the war started, but then it was more like articles about other people’s ideas. I would say that the real writer woke up in me in occupied Kherson, and this is also closely related to the fears and courage needed to express the thoughts and feelings. Now this is a solid part of my practice. It is very important for me not only to express something through symbols and images, but also to verbalise and analyse it and raise it to the surface of consciousness. Only then I consider my artwork finished. Moreover, I learned to do it in reverse order. First write the text, and then encode it in the symbols of the subconscious. To some extent, this is the engagement and synchronisation of both left and right hemispheres of the brain, the creation of a complete picture. For me, it brings much more satisfaction than doing only half.

Fear is a theme I noticed coming up in your work and you stated at a lecture you did at Fries Museum that fear is something you were able to overcome and you gained courage and confidence in its place. How did you overcome your fears?

I can’t say that I invented or learned something new here. Like thousands of years ago, faith and awareness help to overcome fears. It’s like balancing on a board or a rope. Attention constantly tends to fall in the direction of what we are afraid of, to make an “easy” decision and whether we succeed or not depends on how well we can control it and how long we are able to keep its focus on what we want to achieve. When you have proved this from your own experience, then real courage comes as confidence in your ability to change both yourself and reality. In my opinion, this is the true meaning behind “carrying your own cross”. I carried mine though occupied Kherson.

Would you say fear has shaped and influenced the art you make currently? Or has it been shaped by courage?

I think by both. When speaking of courage, it is impossible not to talk about fears.

Are there any themes or ideas you have yet to explore in your work? If so, what are they?

I am currently studying the scientific and psychological researches of disinformation and propaganda, as well as continuing to work in the field of consciousness and I plan to spend more time studying our feelings, quantum physics and artificial intelligence.

What do you hope people can take away from viewing your art?

As Galileo Galilei once said: “You can’t teach people anything, you can only help them discover it within themselves”. This is the essence of my art. I hope to help people to find what is hidden within everyone. What I have found in myself.

What have been the responses like so far from those who view your work? Have you had any particularly memorable feedback?

I received quite a lot of admiration, I was especially pleased with the moments when my artworks awakened insights and helped to find answers to long-standing questions. However, the one I remember to this day was a negative response. It happened when I published a portrait of a man with a Z-shaped stitch on his face, sewn eyes and mouth (Z is a symbol of Russian military aggression against Ukraine). I accompanied it with a text about the alleged apoliticality of Russian citizens who do not want to see and hear obvious things and are afraid to say something against power, hiding their inability to change something in their own country from themselves. In a few days, my publication became viral in social media and apolitical Russians began to write to me their warmest wishes. Someone wished me to sit in the basement (either hiding from the bombing, or being held captive by the Russian army). It was obvious that my package was delivered to the right address and the device triggered. That’s where I finally realised the power of art. That it is capable of breaking through any wall of psychological defense of any thickness, bypassing the most refined rationalisations. For me it was a point of no return. And, finally, I have never been in the basement since the beginning of the war.

When you’re not working, what do you get up to in your free time?

Since the beginning of the war I spend all my free time at home with my family.

Do you have any upcoming projects that you’re working on that you can tell our readers a bit about?

In the future, I should be expected to continue my inner space odyssey and a new project, which, along with the digital photo collages familiar to me, will also include installations, sculptures, video art, performances and many collaborations with other artists.