Who wouldn’t want a white lion the size of a pet cat? The surreal details that Australian painter Ben Smith puts into some of his pieces only emphasize his skill as a painter of the realistic, but Ben is no one-trick pony. That realism is mixed with a healthy dose of the abstract, figurative is enlivened with more than a soupçon of the surreal. Bringing this together into works that speak to the viewer beyond the possibilities inherent in any single technique makes each of Ben’s masterful pieces a true glimpse into the possible, a story of the contrasts and counterbalances of life.

.

Your work is largely figurative with a healthy dash of abstraction and forays into the surreal. How do you feel this has affected your practice in a fine art world often dominated by the conceptual?

It can be tricky being a figurative artist, as it seems many commercial and non-commercial galleries are a little figure shy. However, things have been getting better in recent years and figurative work is making a comeback especially internationally. Resistance to the figure has made me think harder about what makes a good piece of figurative art. Often the key is a strong concept. I don’t see necessarily figurative art and conceptual art as being mutually exclusive.

Do you feel that your studies at the Julian Ashton Art School allowed you develop your practice more in this way, compared, say, to the tuition you would have received in a university degree?

Julian Ashton’s was a great place to get a solid grounding in drawing, tone and colour. After I finished there, I kept on learning and developing the techniques that I now teach in my own studio. If I had my time again I would consider doing a degree as well, as I think I would have enjoyed pushing myself in different directions.

While you were teaching at Julian Ashton was there a common career-related question you were asked by your students? If so – what was your answer?

I can’t remember being asked a lot of career related questions at Ashton’s. “Career” is almost a dirty word there. It was all about making art for the sake of it. In the rest of the art world, this can be a difficult approach to maintain. However, my career advice is to always paint the work you love. That way you can’t lose. Paint the most ambitious work you can paint and get them out there through prizes and social media. Start going out to exhibitions and be open to meeting people. If you’re finding it all too much retreat to your studio batten the hatches and paint until you’re ready to come out again. Hang on to all your art friends.

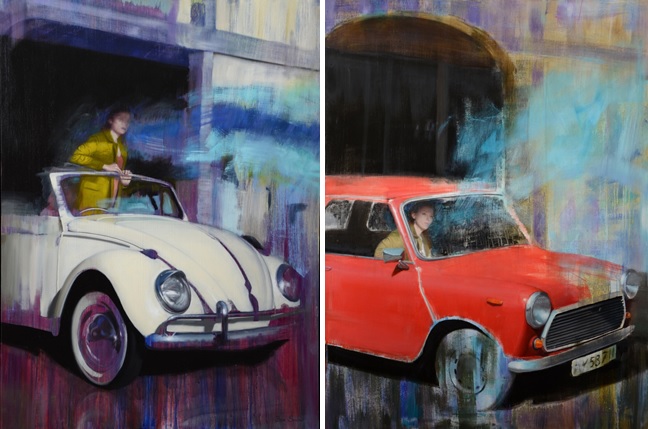

Many works in your recent series “Threshold” have a very nostalgic feel, the settings, vehicles, clothing, all seem to hark back to a simpler time (the 50’s I think, but I may be wrong there!). Obviously, you are too young to have lived through this period yourself, so what appeals to you about that particular time?

It wasn’t a conscious decision to give the works a nostalgic feel. I just happen to like the shape of older vehicles. Some of the works included involve more recent elements and I want to include more elements from our present time in future work.

Given your themes, who are your art heroes? Whose work did you first love and who is rocking your world at the moment?

My first loves were Rembrandt and Francis Bacon. My current favs are Neo Rauch, Justin Mortimer, Adrian Ghenie, Alex Kanevsky and Louise Hearman. So in a sense my interests haven’t changed a lot as all these artists are all linked in one way or another. Generally, my favourite artists are those that combine realism with abstraction and have strong but slightly oblique narratives.

Speaking of first artistic love, when did you decide that this would become your career? Did you have any family background in the arts?

I have almost no family background in the arts although my grandmother did love a bit of watercolour. Growing up I never thought I would be able to become an artist. However, after a couple of years of working as an engineer I threw everything at getting a scholarship to art school and fortunately I got one. I then spent several years working part time while also working very hard at my art. In a strange way, the GFC helped me as I was made redundant from my engineering job and I decided to spend a year doing nothing but paint. At the end of that year when I was almost broke but I fortunately I suddenly started winning art prizes and I haven’t had to do engineering work since.

Could you let us know about your process ~ how do you move from initial conception to completed work, and which part of that process do you find the most demanding?

Sometimes I have a very clear concept for a work from the beginning but mostly I just have some guidelines and I begin to collage, draw and play. Play is very important, I believe you shouldn’t worry about your ideas being good enough, just accept that most of your ideas won’t work and keep playing regardless. In my earlier work, the play would, in a sense, end once I started painting and I got down to the business of making a picture work. However, in my newer work the play with colour, texture and abstraction lasts up until the last brushstroke. I find the rendering of mechanical objects the most demanding.

When you are planning your work, how do you decide where to transition from the figurative to the abstract? While with some of your pieces this abstraction seems to add to the haze of time, like the fog of memory, with others it seems to be more emphatic, asking more questions of the viewer.

I really wish I knew the precise answer to this question as it would save me a lot of anxiety. It is an exciting but difficult part of my painting process. Basically, if a certain section of a painting gives me a little thrill I leave it alone and work on another part of the picture. If I’m still just as happy with it later it will probably stay around for a while.

Now to the future, what are you working on at the moment, and what shows do you have coming up?

I’ve been drawing Australian megafauna. I don’t want to say too much about it as ideas at this stage are very fragile. It’s almost as if as soon as you speak about them, they up and leave you.

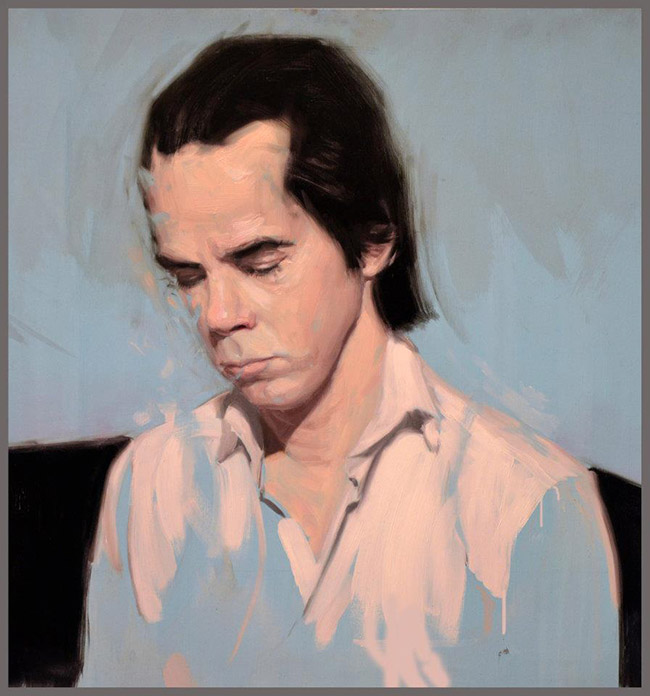

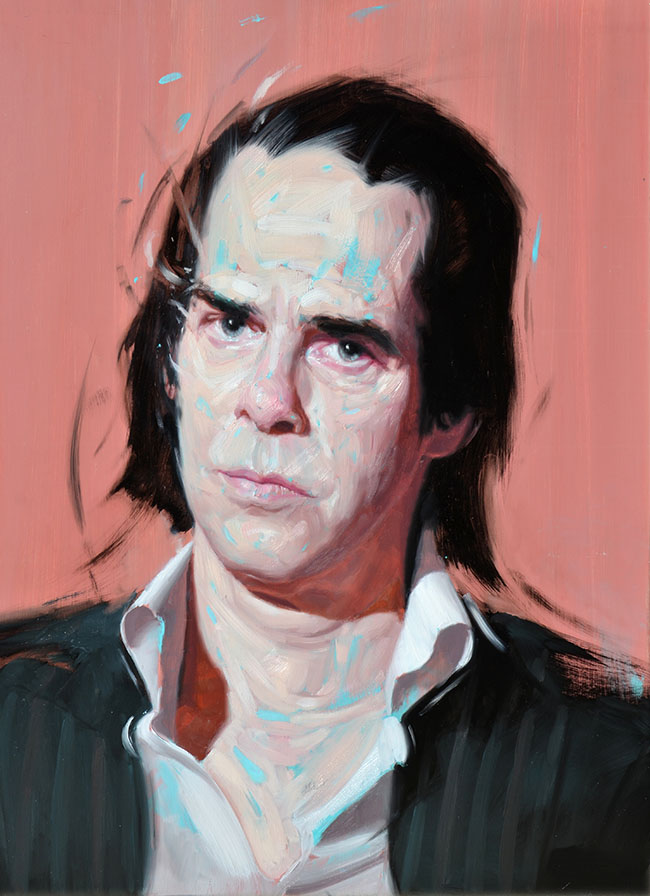

Ben Smith talks about his art, influences and the time he painted Nick Cave for the Archibald.